Local leaders say this year’s sales tax vote could have “substantial and very serious” consequences for KC’s bus system.

Josh Merchant

The Beacon

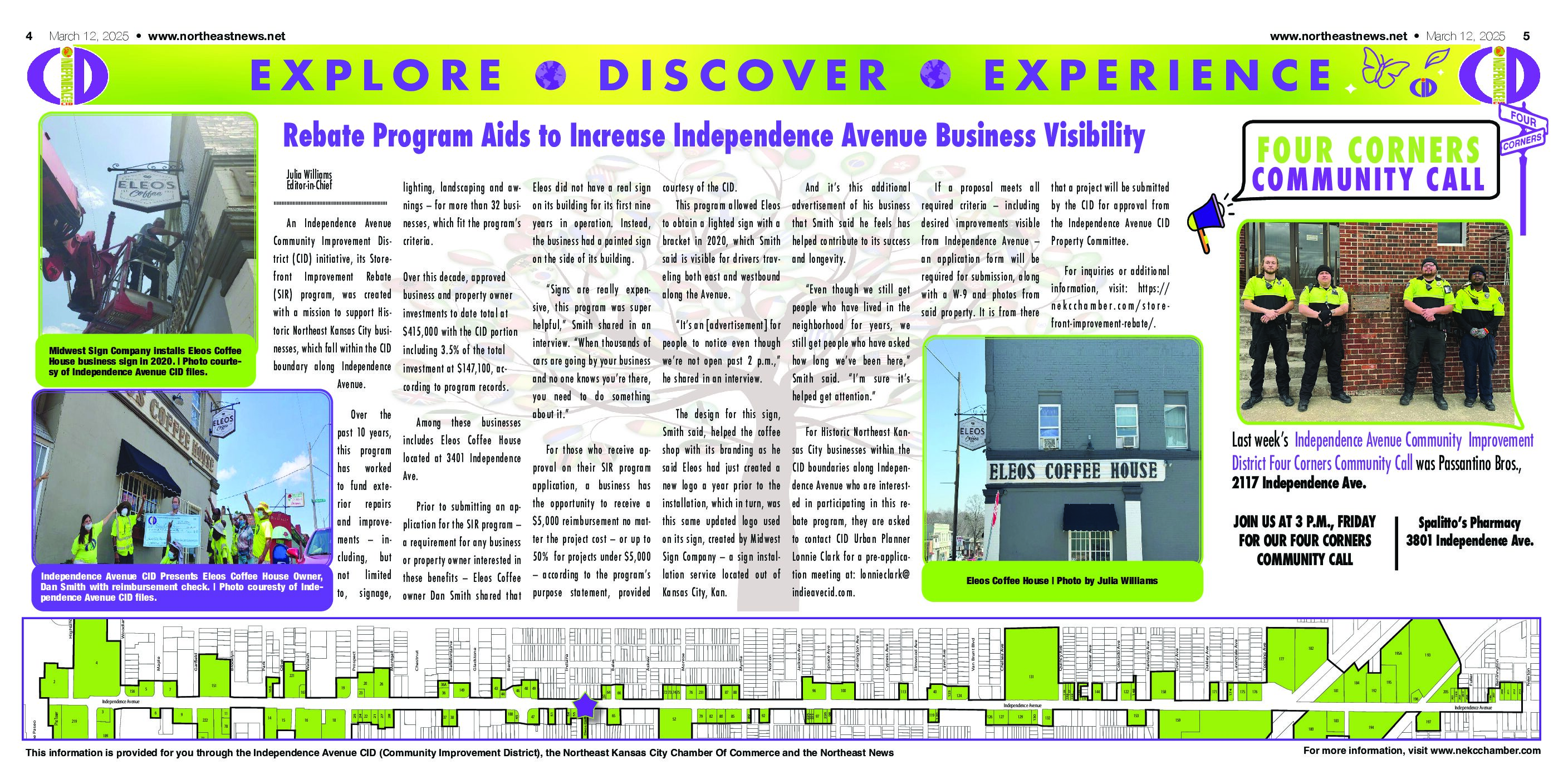

The transit agency says that if voters reject the bus sales tax, it will be forced to cut weekend service on some bus routes and eliminate other routes entirely. (Chase Castor/The Beacon)

For 20 years, people in Kansas City have paid an extra 3/8-cents sales tax on every purchase they made, to subsidize bus service.

On Nov. 7, voters get to decide whether to continue that tax, which hits poorest families the hardest, or whether to effectively cut nearly a third of the bus service that working-class residents rely on most heavily.

If they choose to ax the tax, thousands of Kansas City bus riders may find themselves with no way to get to work, and roads across the metro could become clogged with more cars.

“If it doesn’t pass, it’s going to hurt people,” said Frank White III, CEO of the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority. “That’s just the ugly truth.”

The sales tax provides about 30% of the KCATA’s budget, and if Question 1 fails, the KCATA says it will be forced to cut weekend and night service on some bus routes and eliminate others entirely. At least 100 transit workers will lose their jobs, and workers across the city will be stranded with no clear way to get to work, doctor’s appointments or child care.

Some critics complain the sales tax disproportionately hits lower-income families who spend a greater portion of their wages on goods and services. And some Northland leaders contend they don’t get their fair share of bus services north of the Missouri River.

The official ballot language is as follows:

Shall the City of Kansas City continue a city sales tax for the purpose of developing, operating, maintaining, equipping and improving a public bus transit system for Kansas City, pursuant to contract with the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority, as authorized by Section 94.605 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri at a rate of 3/8% for a period of 10 years?

Same tax, same bus service

In its heyday in the early 20th century, Kansas City’s previous streetcar network ran as a private business paid for with fares. But when cars and highways transformed the city, the mass transit business model crumbled.

So Missouri and Kansas created the KCATA, and for the past few decades, buses in Kansas City have been sustained by local taxes and help from Washington.

Voters first OK’d a 3/8-cent sales tax in Kansas City in 2003 and reauthorized it in 2008. If it’s approved again, it will last through 2033. This year’s Question 1 asks voters if they want to renew the existing tax.

The sales tax can only fund bus service for Kansas City residents — the revenue cannot be used in Kansas or neighboring Missouri cities.

It cannot fund projects like the KC Streetcar or some future rail line to Kansas City International Airport. Instead, the money can only go toward buses, the IRIS ride-share program and RideKC Freedom, which gives rides to people with disabilities.

If voters say no to the extension, the sales tax disappears and triggers a 30% cut to the KCATA budget and a deep slash in bus routes within the city.

Who relies most on public transit?

Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas and several City Council members back the sales tax, arguing it’s crucial to keep daily public transit running. Without it, they argue, workers will struggle to get to their jobs and the city won’t be able to shuttle people during the 2026 World Cup and/or other big events.

“You can’t have World Cups. You can’t have big games,” Lucas said. “You can’t have Taylor Swift visiting if we’re not actually doing the work to make sure we have a world-class public transportation system.”

Advocacy groups like the Missouri Workers Center, the Sunrise Movement KC and the union that represents bus drivers say the transit system is essential to the day-to-day lives of workers and Kansas Citians who cannot drive.

Terrence Wise, a leader with Stand Up KC and the Missouri Workers Center, said that when he worked at fast-food restaurants, nearly all of his coworkers relied on a bus to get to work. At 3 a.m., the night shift workers would watch the bus stop through the window to see when their replacements would arrive. If the bus was delayed, most of the staff would be late.

“Workers depend on a strong public transportation system,” he said. “That’s why we definitely want to say yes to the sales tax measure.”

Wise said buses are the only way some people can get to work, to doctor’s appointments or to fetch their children from child care.

“This is bigger than a bus being on time, or having the ability to get on a bus at 4 a.m,” he said. “It’s the ability of a city to survive and for its citizens to maintain livelihoods, keep a roof over their heads and keep their health care in check.”

The KCATA says users of the bus system tend to live east of Troost Avenue, a historic economic and racial dividing line in Kansas City created by racist housing practices.

Northland reluctance?

Northland officials have used the ballot question to raise complaints that the KCATA doesn’t include a strong enough voice for their part of the metro.

Three weeks before the election, the presiding Platte and Clay county commissioners criticized Lucas for picking his own choices to represent the Northland on the KCATA board over people they had recommended.

Commissioners Scott Fricker from Platte County and Jerry Nolte from Clay County urged residents to consider that “taxation without the legitimate representation as guaranteed to us by law” when voting on the Question 1 sales tax.

Under the bistate agreement that established the transit agency, Clay and Platte counties each give the Kansas City mayor a list of three recommendations for KCATA’s board. The mayor then appoints one person from each county to serve on the board. Lucas picked two people who weren’t nominated by Northland officials — Tyjaun Lee in Platte County and Jade Liska in Clay County.

Nolte told The Beacon that he does not have concerns with the specific people the mayor chose, but he takes issue with the mayor not following the process outlined in the statute.

“We do not get back near the investment we make as far as the taxes we pay,” Nolte said. “We’ve been complaining for a long time about not having sufficient lines up here to get people where they need to go.”

But it could be difficult for the gears of City Hall to work quickly enough to replace two members of the KCATA board before Nov. 7 — if Lucas wanted to make the switch. A representative from the KCATA said that Lucas can replace the board members before their terms expire in 2025 and 2027.

In the meantime, 30% of the bus system’s funding is at stake. The failure of the bus sales tax measure would result in cutting bus routes and transit service for Kansas Citians with disabilities — including services north of the river.

“The consequences … are substantial and very serious,” Nolte said. “With such an obvious solution, that is to give us the representation that we’re entitled to, why would anybody take the chance on those kinds of dire consequences when the solution is relatively low impact?”

Nolte said he’d back the sales tax extension if Lucas at least started the process of replacing the two Northland KCATA board members.

Lucas declined to comment on the appointments from the Northland.

Other ways to fund buses in Kansas City

Kansas City Councilmember Melissa Robinson, who represents the 3rd District, supports the sales tax extension in Question 1 but said it asks too much of lower-income families.

“This is a sales tax,” she said during a committee meeting in August. “Sales taxes are regressive.”

Robinson said the city could better afford to pay for public transit if it cut back on tax breaks it hands out for some development projects.

Meanwhile, White said the KCATA is working to negotiate with businesses to pick up part of the cost of getting their workers to job sites — particularly workplaces beyond where buses typically run.

The agency is meeting with developers to spur “transit-oriented development” that factors in how workers will commute.

“You can’t create a private problem and expect a public solution,” White said. “You can’t come to us and say, ‘We need transit,’ and think you’re not going to put some money into the kitty.”

This story was co-published with the Beacon, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.