Recently the News Dog was invited by the Kansas City, Mo., Police Department (KCPD) to participate in their officer-involved shooting (OIS) simulator drills at the regional police academy at the Shoal Creek Station. I was part of a group of roughly 15 individuals – a few other media folks, but mostly community and business leaders from across the city – to participate in an all-day event that consisted of three drills involving real time “shoot or don’t shoot” scenarios that officers could confront.

Since Chief Rick Smith was appointed, the scenarios have been run loosely on a quarterly schedule. COVID slowed that, but the chief said he’d like to make it a more regular event to allow the community the opportunity to see what cops do on a daily basis.

“We want to give the opportunity to walk in an officer’s shoes and to see what an officer goes through every single day on the job,” said Police Chief Rick Smith. “It’s not all about the life and death, more about an officer’s split second decision making that we train for day in and day out and continue to tran for, that’s what we wanted to show.”

As part of the simulation, participants are issued a radio number (I was radio #112) and a mock sidearm that actually cycles and recoils just like a regular department-issued weapon, but instead shoots bursts of compressed air. As real as it gets without running live rounds through in an actual .40 caliber handgun.

According to Captain Brian Bartch, commander of the training unit, the purpose of the exercise is to allow citizens the opportunity to see exactly what officers go through in their careers.

“The biggest thing is the fact that we have an opportunity to bring members of the community in and let them experience what an officer sometimes has to go through,” Bartch said. “The experience may be a critical incident with the possible need for use of deadly force and the decision process that surrounds that situation.”

Sergeant Ward Smith, supervisor of the Firearms Training Section, echoed Bartch.

“I think that’s important for people to realize that police officers are human beings too,” Smith said. “We’re called upon to do some sometimes dangerous things, sometimes mundane things, sometimes mind blindingly boring things, but they get a snapshot of what it is to be a cop through these exercises.”

Each of the three simulations put us, the participants, in a “shoot or don’t shoot” scenario with the help of police officer actors playing the “bad guys” in each scenario. Note to our readers, since these police officer “actors” have already lived through the scenarios in real life, they’re at least two steps ahead from the get-go on how we civilians are going to react. On the converse, we as participants also knew the crap was going to hit the fan, we just didn’t know when.

For each of the simulations, we were partnered with a field training officer (FTO) who first briefed us on the scenario that we were participating in, then who acted as our “backup” officer during the simulation scenario.

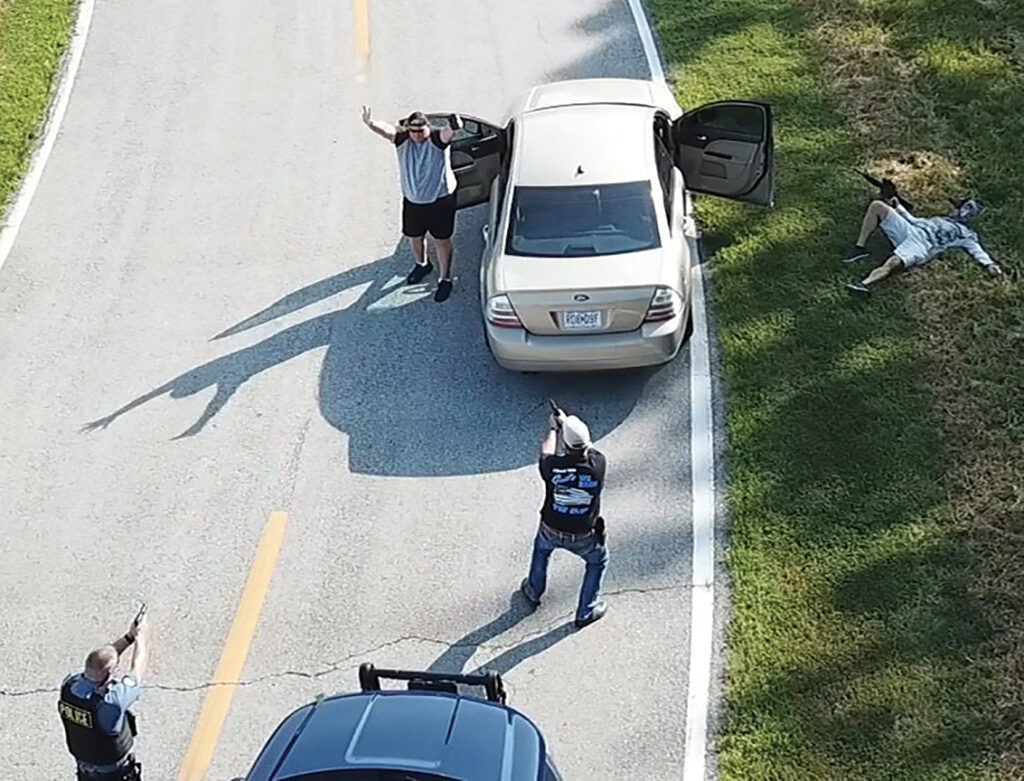

Scenario number one was a routine traffic stop. The “stop” took place on a closed course at the academy driving range where the suspect vehicle had just blown a red light and initiated an illegal turn. Our FTO turned on the lights and sirens, which initiated the stop, and the vehicle, much to my surprise, dutifully pulled over. While constantly watching the actions of suspects in the vehicle, we exited the police vehicle and slowly approached the stopped car, the FTO on the driver’s side, and me on the passenger side, approaching slowly. Before I could get to the rear of the suspect vehicle, its doors suddenly flew open and the suspects exited the vehicle, the driver surrendering, hands in the air holding a cell phone. The passenger, however, armed with an AR style rifle, immediately began to “shoot” at me. Before I was able to unholster my weapon, the suspect was able to put at least three rounds in me.

The upside? I was able to put at least one round into the suspect. Wishful thinking says maybe two, but by that time – in real life – I’m on the pavement bleeding out.

Time from when the suspects exited the vehicle to the end of simulation? Less than two seconds. Heart rate? Over 120 beats per minute. Time frame for “shoot or don’t shoot” decision? Less than half a second.

Scenario number two involved a “known” armed felon, holed up in an upstairs bedroom of a residential structure. The felon’s roommate had summoned officers to the house because he was unsure if the felon was mentally stable or not, based on his actions and behavior. Once again, our FTO for this simulation briefed us on the situation and the scenario began. We approached the house and the roommate met us outside the “front door” and explained the situation. After advising the roommate to move away from the house for safety purposes, ours and his, we entered the darkened structure and began “clearing” each room before moving upstairs.

As we slowly moved upstairs, our weapons were drawn, held in what’s called a “low ready” position with both hands in front of us, with the muzzle pointing downward, but ready to quickly put into the “fire ready” position. Our FTO’s dim flashlight only partially illuminated the dark stairwell and hallway. After ascending the stairs and turning a corner in the hall, we tried every closed door. If it’s locked it is technically not part of the exercise. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw movement at the foot of a bed in a dark bedroom that’s one door past an open room that requires clearing. Decision time. Do you acknowledge the movement immediately and pass the uncleared room, or clear the room and immediately demand from your position in the hallway that the suspect show himself and his hands?

Our partner and his weak flashlight help make our decision for us. He clears the immediate bedroom while I address the unknown moving threat in the dark bedroom. Raising my weapon to the ready position, I shouted verbal commands to the suspect, demanding he stand up with his back to us and show us his hands. The suspect begins to comply, slowly coming to one knee and putting his hands in the air as I continue to give verbal commands. Then his right hand disappears under the bed covers.

Shoot or don’t shoot?

Not knowing whether there’s a weapon under the covers, I immediately discharged my weapon three times, eliminating the perceived threat. Almost immediately our FTO yells “end of exercise,” and the lights come up. Our “suspect” stands up and in the same hand that he hid under the covers, displays a cell phone, stating, “I’m now calling my lawyer.”

Time elapsed from suspect encounter to end of exercise, again, less than five seconds. Time frame for “shoot or don’t shoot” decision, again, a fraction of a second. Heart rate, roughly 125 beats per minute.

While all the training scenarios are based on real experiences, this particular role play is based on the experience of KCPD Captain Paul Filges who was on hand to relay his experience during that call. Filges ultimately didn’t pull the trigger and the suspect was taken into custody.

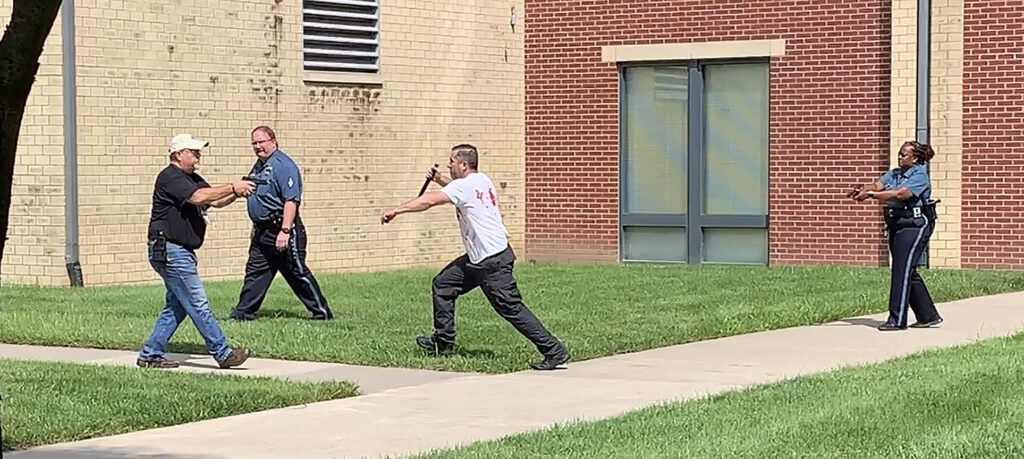

Our last scenario involved a school athletic facility where over 200 middle school students would be present in less than 15 minutes. The problem was an emotionally disturbed party (EDP), possibly high on drugs, had exited the building and was somewhere on the premises. The subject had also been beating his head against the walls of the building and was armed with a bayonet or machete-style knife.

Our FTO for the exercise told us the suspect had been yelling about doing harm to himself and had blood all over his t-shirt. The suspect had wandered outside toward the athletic field the students would be on shortly but he was not currently in sight. We confirmed with our FTO – who on this call does not partner up with us – descriptors of the suspect, confirmed direction of travel and exit of the school building, clearing every corner space behind us as we advance on foot to make contact with the suspect, our weapon again in the low-ready position.

As we rounded a corner we saw the suspect facing a brick wall, muttering and banging his head against the wall. The suspect sees me and begins advancing, drawing the knife from the back of his waistband, slashing the weapon across his chest screaming, “Kill me, shoot me!” With our weapon raised in the fire-ready position, backing up to maintain distance between the suspect and ourselves, we continued to give verbal commands to the suspect to stop advancing, get down on the ground, and drop the weapon.

The suspect, however, is gaining ground, as he can walk faster forward than we can backward. When he is within six or seven feet, the suspect brings the knife to an overhead attack position and begins to run toward me.

Shoot or don’t shoot?

When the suspect was within roughly four feet of me, ignoring my verbal commands and aggressively displaying his weapon, I discharged my duty weapon three times into the suspect, thus eliminating the threat.

Time between suspect encounter and elimination of threat? Roughly eight to 10 seconds. Time frame for shoot or don’t shoot decision? Less than a second. Heart rate, again, roughly 120 beats per minute.

At the end of the three exercises, the score card reads, suspect deaths: 2, participant deaths: 1, second guesses after scenarios: 3 for 3. All of these scenarios are designed to show civilians not only what could possibly unfold in a split second “shoot or don’t shoot” situation but also how quickly a scenario can go from controlled to chaos, literally in the blink of an eye. It should also be noted that while these were realistic training scenarios, they were just that. Training scenarios with a classroom debriefing session afterward, watching the video footage of our actions and getting a chance to see how horribly inept we looked or how many “rounds” we put into everything but what we were aiming at.

However, officers involved in a real life shooting are immediately pulled off street duty and put on administrative leave while the Highway Patrol and the Internal Affairs Unit thoroughly investigate every aspect, every thought process, every microsecond of how the incident played out.

Additionally, the Department’s Notable Events Review Committee scrutinizes each event from a criminality standpoint, from a policy standpoint, and finally from a training and development standpoint in order to determine if any training practices need to be updated, developed, or modified.

“Some really good information comes out of the Notable Events Review Committee,” said Smith. “Because as soon as we think that we’ve seen everything and done everything, something new pops up we never thought about, so how do we handle it? It’s a good learning experience for everybody. It’s an opportunity for us as police officers to think about things that might occur and plan ahead for them instead of coming in after the fact and going, ‘Okay how do we keep this from happening again?’”

In real life, the crime world doesn’t stop. As quickly as you exit one tense situation, another call comes over the radio and you’re dispatched to a completely new situation you’ve got to address with fresh, unbiased eyes. Many times that leaves almost no time to decompress from one situation before being faced with a completely different situation. With staffing shortages thrown into the mix, that in-car radio doesn’t quit just because an officer needs a 15-second break to gather their thoughts.

“You’re going to be going on multiple calls throughout your shift, and you’re going to be thrust into people’s lives, and one of two things is going to happen: you’re either going to have a positive impact on them and hopefully help them get through that situation they’re going through, or you’re going to have a negative impact and possibly make it even worse,” Bartch said. “That’s an awesome responsibility but I’ll tell you what, it’s one of the most fulfilling jobs I think you can have.”

“I would stack a good district officer up against any good problem solver in the world,” Smith said, “because they’re confronted with so many things. If you’re not a good problem solver, you probably won’t last very long as a police officer.”

The News Dog would like to thank Chief Rick Smith and Officer Jason Cooley for the invitation to participate in the simulation training. I would also like to thank the staff at the academy, including Sergeant Ward Smith and Captain Brian Bartch, a former Northeast CAN Officer back in the mid 1990’s, for this extremely insightful exercise.