Abby Hoover

Managing Editor

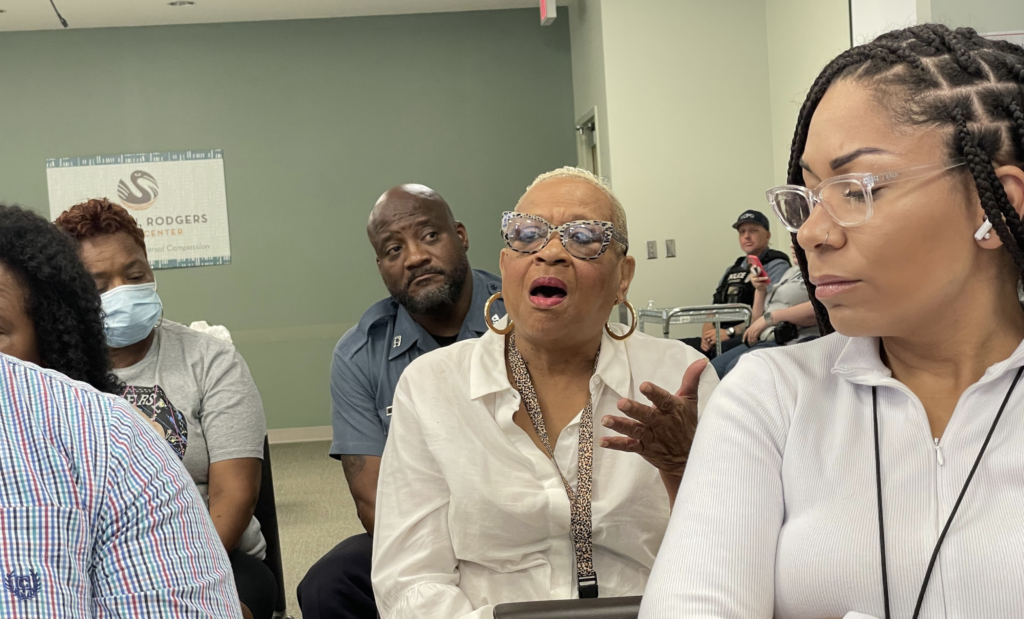

Samuel U. Rodgers Health Center (SURHC) on Euclid hosted Kansas City Police Department (KCPD) Chief Stacey Graves for a community conversation on Wednesday, Sept. 13.

The conversation ranged from homicide cases to shootings in Kessler Park, how to increase patrols in specific areas, neighborhood watch, recruitment for the understaffed department, and crime hot spots on the East Side.

“The objective today is to bring community and law enforcement a little closer,” said Rory Kirk, Community Advocate at SURHC. “I think that’s one of the big keys, people talk about it all the time. The Northeast section here in Kansas City, it’s growing. We’re obviously seeing a lot more growth, which sometimes can, unfortunately, mean a lot more crime. So obviously people want to know what’s going on in the community. Chief Graves has been gracious enough to come out and talk to us. I think it’s a great day because in many cases you don’t get that from law enforcement leadership throughout the country.”

Graves, a Kansas City metro native, said when she came into the position, one of her top priorities was to build bridges and strengthen relationships with the community. She said she knew that started with listening to expectations, suggestions on how the police can better serve Kansas City, and how it can be made a safer place.

“We’ve heard a lot about violent crime,” Graves said of discussions around the community. “Obviously we know what’s going on with our violent crime problem here in Kansas City, and I’ve got to tell you, the silver bullet to that is Kansas Citians. Everyone should be concerned if there’s a violent crime or life taken by violence in Kansas City, and everybody needs to ask themselves what they can do and how they can get involved in trying to make the city safer. “

Working toward a solution, KCPD has moved into a citywide approach to violent crime, Graves said.

“That means pulling in all kinds of resources to assist in the whole bigger picture of violent crime, its root causes and our approaches to it,” Graves said. “Coming into the summer, we started to look a lot internally… as far as our approach to violent crime. We anticipate a written violent crime plan to come out in the beginning of the year, the beginning of the year is kind of going to be a reset.”

KCPD is starting a new shift in patrol to better provide 911 response from patrol officers, and in that they hope to do a lot of initiatives related to violent crime. One of those is focused deterrence.

Interim Chief Joseph Mabin created the Community Engagement Division and selected Major Kari Thompson, who was most recently major at the East Patrol, to lead the division back in December.

“They are out in the community every day,” Graves said. “They are having conversations or they’re bringing in resources and assisting, and also, obviously, we work in the three pillars of prevention, intervention, and enforcement.”

The Community Engagement Division includes the department’s Crisis Intervention Team, social workers, community interaction officers, crime-free multi-housing officers, chaplains, and a new LGBTQ+ liaison officer.

“The Crisis Intervention Team deals with mental health and the houseless population,” Sgt. Ashley McCunniff said. “So we partner with the community mental health centers, and we take the Community Behavioral Health liaisons out on visits to people’s homes, to try to engage them in services so that they’re getting the appropriate care versus just a police response. We’re trying to direct people to where they need to be, which is mental health resources and not the police.”

Capt. Luther Young with the department’s Community Engagement Division, said it’s essentially a division that puts a focus on interacting with citizens, businesses and local organizations throughout Kansas City to keep a pulse on what’s going on.

“What are some of the concerns? How can we address those concerns? And we’re taking a holistic approach of working with various groups like KC 360, KC Common Good, and those are ways that we can sort of identify what these areas of concern are, provide adequate resources, and then come back and sort of convened to see you know, what was working, what wasn’t working and where we can make tweaks,” Young said.

The Board of Police Commissioner’s Office of Community Complaints, which was started in 1968 and is the longest continuously operating civilian oversight office in the country, was also represented at the meeting.

“Since the inception, our main mission is to review allegations of misconduct against members of the Kansas City Missouri Police Department,” Executive Director Merrell Bennekin said. “However, we try to do more than that. We try to be problem solvers where we can also assist with connecting people with resources. We’ve been blessed to be able to work closely with the Community Engagement Division because we have a lot of overlap in what we do and what they do, and the issues that they’re dealing with and what we see coming through our doors, so it’s just been a wonderful experience.”

Bennekin said he’s excited to see the shift in philosophy in terms of enforcement. They’re seeing a change in the types of contacts and engagement that have been coming through their doors. He said they’re always looking for feedback and helping people get their problems addressed.

Graves recognized Pendleton Heights neighbor Mark Fenner in the audience and asked him whether gunfire in Kessler Park is still an issue, which he confirmed it is. He recently heard a neighbor’s friend had been hit by random shooting, and he is interested in getting increased patrols like he had noticed on the Country Club Plaza over the summer.

While Graves was not aware of the City directing KCPD to increase response on the Plaza, she said that patrols often target entertainment districts in the summer months for traffic flow, safety, and engagement.

“I know that the conversation that we have with City Hall is citywide, and that is an equitable distribution of resources to places where we are seeing a rise in violent crime, where we know more violent crime has historically occurred,” Graves said. “That has not been for us to say that we will be just concentrating on that area.”

Fenner brought with him to the meeting a Ziploc bag of shell casings he had collected in Kessler Park over the past year. He doesn’t use a metal detector or magnet, but often spots them while cleaning up trash.

“I walk through the park every day and pick up trash, and when I see one of these, I figured I would stick it in my pocket,” Fenner said. “So, you know, I look a little harder after I’ve heard of shooting the previous night.”

Last May, a disc golfer was shot in Kessler Park during a tournament. The incident prompted the group to cancel events in Northeast Kansas City altogether. While that shooting resulted in a major injury, it was not the first, nor the last incident of gunfire in the park.

“Obviously it’s a huge problem for us,” Fenner said.

Neighbors get advice to put more eyes in the park, create positive activity, and call in shots fired. However, it often occurs in the middle of the night in the expansive park.

“That’s why it’s so hard for the police to do anything about it because by the time we’re on the phone, the people are gone,” Fenner said. “They’ve definitely got to do something proactive.”

He asked Graves how many calls it takes to get a response or get someone taking action against that problem.

“I’ll let you in on a little bit of investigative tactics,” Graves said. “So if we continue to have calls for shots fired – and could just be one – we deploy officers in that area when they’re not on calls for service to try to suppress that activity in that area.”

They also look at the Risk Terrain Modeling, which informs them what about the specific environment makes people feel comfortable committing crime there.

“It’s in a park, so there’s not a lot of eyes,” Graves said. “There’s not a lot of people so that’s something that we look at, but if there’s something that we can do, we will report that to the City. That’s that city-wide approach about crime where the City could come in, look at the lighting, whether it’s facilitators – if there’s a business that’s across the street that’s bringing people there and they’re congregating in the park, something like that – we will look at all those factors.”

They then use Data Informed Community Engagement to share crime data with neighborhoods or stakeholders to problem solve.

Recently, East Patrol has focused on enforcement and engagement on Independence Avenue for a variety of issues ranging from homelessness to theft, violence, and drugs.

“We’re very excited to know that a group of officers selected that hotspot as a project, and we met with them two weeks ago Saturday,” said Bobbi Baker-Hughes, manager of the Independence Avenue Community Improvement District, of the intersection at Bales that she calls the “worst corner in Northeast.”

Others asked questions about enforcement of gun laws and how to get guns out of the hands of juveniles.

“Our investigators have talked to the juvenile justice system, or family court, here in Kansas City to make sure that juveniles are held,” Graves said. “A lot of times juveniles are just, you know, it’s like, ‘What’s best?’ but we have gotten that to where they will pull juveniles with guns, just to put them in a safe space.”

Graves clarified that the department does not write gun laws, but they have a duty to enforce them. She said they try to drive home the message of locking up guns in the home and do their best to prevent retaliation.

An audience member said relationships between the community and police officers are strained because most people don’t see police until there’s a crime. She asked why officers don’t live in the neighborhoods.

Staffing shortages and a loosened residency requirement are both factors, Graves said. Officers no longer have to live in Kansas City, Mo., and that has helped with recruitment, but the department is still 300 officers short, she said.

“I’m not giving an excuse, because we’ve had to make some cuts and some priority moves to make sure that we have officers on the street to answer 911 emergency calls for service,” Graves said. “This is happening nationwide.”