By Celisa Calacal

The Beacon

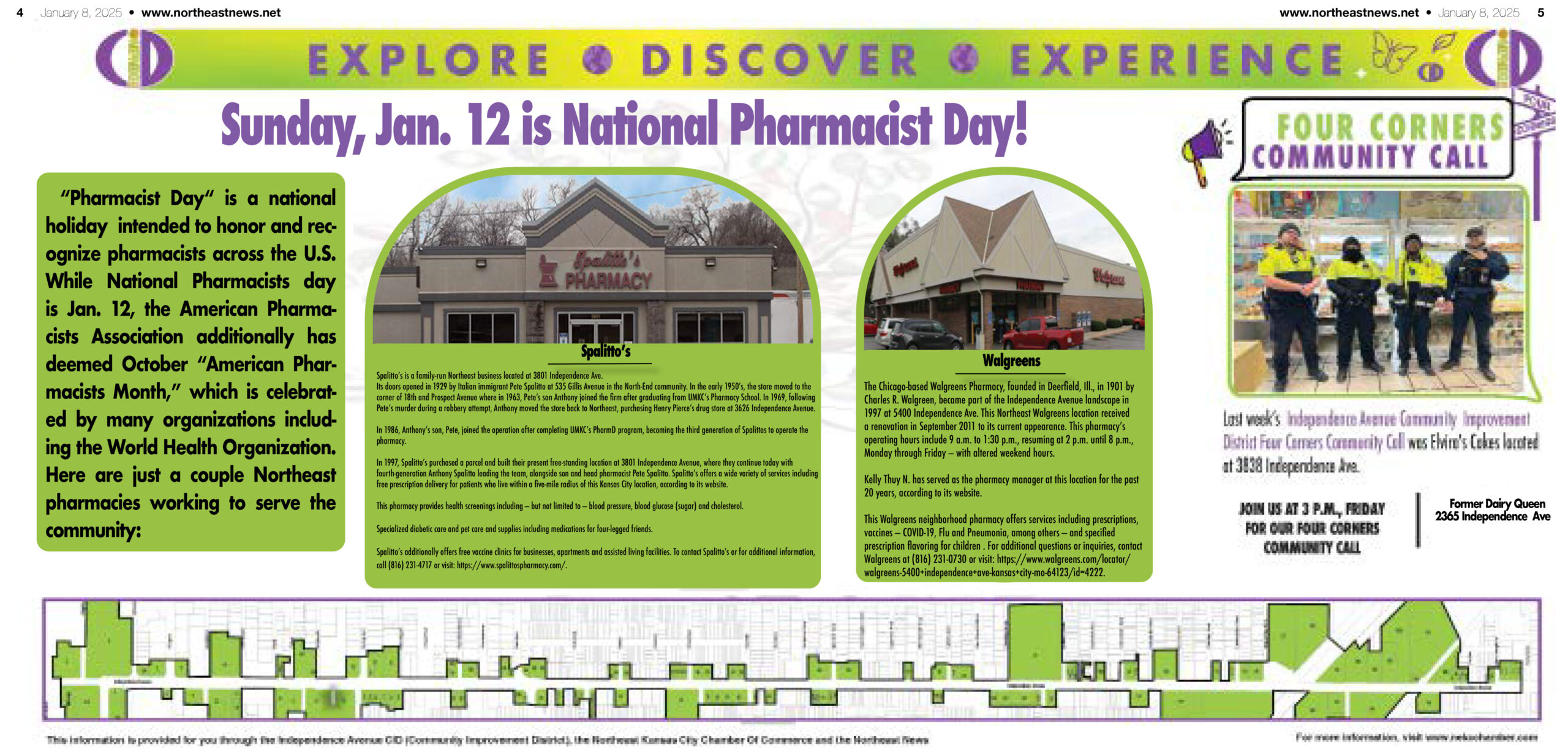

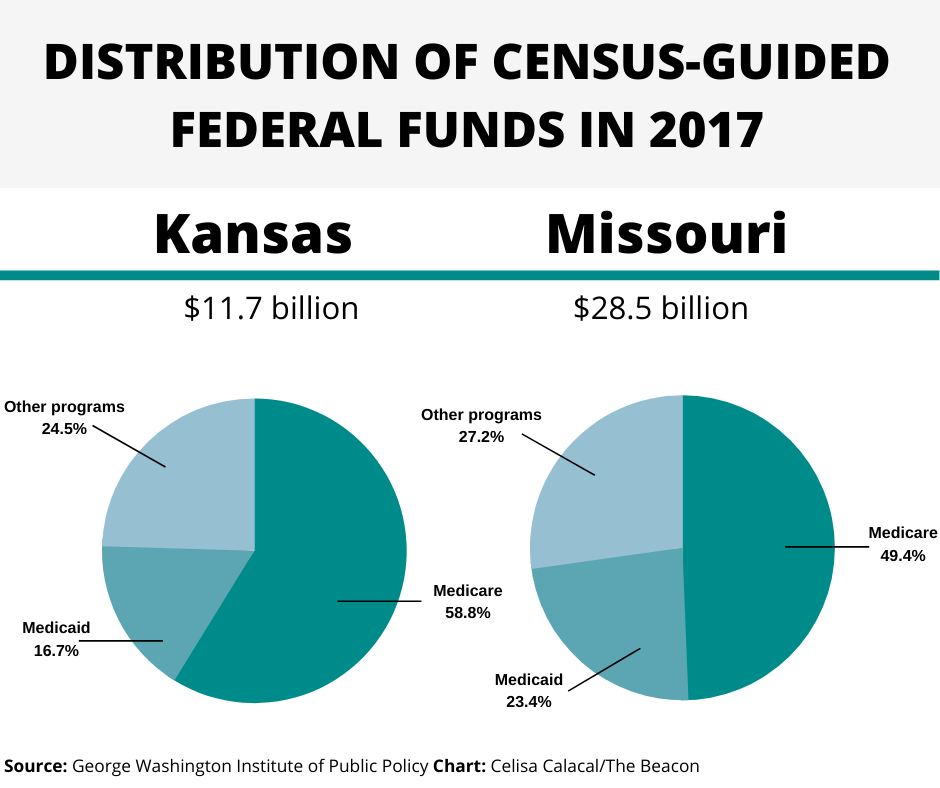

If more Missouri residents had completed the 2010 Census, there’s a chance the state wouldn’t have lost a seat in Congress. Kansans could have received more funding for essential programs like Medicare and Medicaid. And Kansas City could have qualified for more coronavirus relief funds from the federal government.

Performed every 10 years since 1790, the U.S. Census has a single, daunting goal: Count every person in the country. The results provide a bedrock of data that is used to determine federal spending on a state-by-state basis for dozens of critical community programs, ranging from health care centers and Head Start to affordable housing.

“It is about funding. It is about representation,” said Jenny Garmon, who is leading the 2020 Census program at the Kansas City Public Library.

But not everyone is represented. According to research from the George Washington University’s Counting for Dollars Project, an additional 1 percent undercount in the 2010 Census would have resulted in a loss of $1,272 per person in federal funds. Even before the pandemic, the Mid-America Regional Council estimated a similar undercount for the 2020 Census could result in a loss of $48 million per year in Kansas City.

Now local leaders fear a bigger undercount in 2020 — and its potential impact on services. The risks of an undercount are even higher for people of color, children, rural communities, and other vulnerable groups who rely on social safety programs that distribute funds based on Census data.

An early snapshot from the Census Bureau places the current Census response rate in Kansas City at 54 percent as of May 18.

“If we have that happen again, we’re really going to be hurting,” Garmon said. “And it doesn’t have to be that way if we work together.”

Reaching underrepresented communities

MARC estimates that the U.S. population was undercounted by 1 percent in the 2010 Census.

But communities of color saw an even higher undercount: About 2 percent of African Americans and 1.5 percent of Hispanics were not counted in the previous Census. Other demographics that are considered hard to count by the Census Bureau include renters, children, people in rural areas and those with limited internet access.

Many of the hardest-to-count communities — defined as a Census tract with a 2010 Census response rate of 73 percent or less — are located in areas of Kansas City that are primarily made up of communities of color, where residents are more likely to be low income, lack internet access and have limited English proficiency.

Hispanic people are a particularly hard-to-count community in Kansas City, though they make up roughly 10 percent of the Kansas City metro’s population, according to MARC.

In addition to facing socioeconomic barriers, Irene Caudillo, president of El Centro, said fear of government and potential immigration raids can influence low response rates from Latino families, particularly mixed-status families. Last year, President Trump attempted to include a citizenship question on the 2020 Census, but it was struck down by the Supreme Court.

“The political rhetoric has really positioned the community to have doubt, insecurity, and remain very critical about what they sign and what they fill out and where it goes,” Caudillo said. “There’s this distrust in government and where their information goes.”

Getting an accurate count of Latinos has become a major focus of local Census efforts. To quell anxieties, the Complete Count Committee in Kansas City partnered with 30 to 40 local organizations in the area to boost Census count efforts in the city and reach hard-to-count communities.

Rick Usher, assistant city manager for the City of Kansas City, Mo., said it’s important for residents to connect with trusted community leaders and organizations.

“They use a lot of trust that the federal government has lost in this process,” Usher said.

Establishing that trust also means having representatives from different communities who can speak to and understand community members’ concerns. Jellie Duckworth, community outreach organizer at Westside Housing Organization, sees herself as an example of this relationship.

“I’m Mexican-American, I speak the language,” Duckworth said. “So being a representative of the community that I look like and have roots in is really important when you’re advocating in these environments to do the Census.”

Changing tactics after COVID-19

To strengthen Census count efforts, regional and local Complete Count Committees have partnered with local organizations.

“We have over 130 partners in the region who are willing to help, but because of the COVID-19 they can’t conduct the in-person assistance like they have wanted to,” said Catherine Couch, public affairs coordinator at MARC, which is leading the Kansas City Regional Complete Count Committee.

Because of disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the Census Bureau has extended its deadline for completing the Census to October 31. In addition, Census field operations have been postponed to June 1 — at the earliest.

What’s new this year is the ability to complete the Census online, the first time in its history. Although many hope the online option will encourage more responses, the change also exposes the digital inequities that can exist in communities. Initiatives to connect with families who lack internet access at home have been paused because of the pandemic.

“That poses a barrier for those households that don’t have the technology,” said Marlene Nagel, director of community development at MARC. “Or they are unfamiliar or uncomfortable using the internet to give information about themselves and their households online.”

Organizations involved in Complete Count efforts have been forced to change their engagement tactics. Many have relied heavily on texting, email and social media promotion to remind community members to fill out the Census and answer questions. Other organizations, like El Centro, which has locations in Olathe and Kansas City, Kan., have tried more nontraditional methods like reminding people to complete the Census as they distribute food to community members.

Caudillo said the group also tried a neighborhood ride-through with signs on cars promoting the Census. She said they chose areas with a high population of Latinos who had not yet completed the Census.

“They were talking about the importance of the Census, not to forget to fill out your Census while you’re at home, what Census is about, and then, if you need help, to contact El Centro,” she said.

Complete Count Committees are contending with the reality that those in hard-to-count communities are also likely to benefit from the programs that rely on funding calculated by Census data. Data from ChildTrends found that a 3 percent national undercount of Hispanics in the 2020 Census would lead Missouri to lose $6.9 million in federal funding per year.

El Centro tries to emphasize the 10-year lasting impacts of the Census data on the federal programs that many Latinos depend on.

“We try to bring it to what’s personal for them,” Caudillo said. “So that the idea is they’re understanding, if you fill this out, it’s the ability for our community to be able to get that money … to be sent back to our community for these programs.”

Celisa Calacal is the assistant editor at The Beacon. Follow her on Twitter or email her at celisa@thebeacon.media.