Michael Bushnell

Publisher

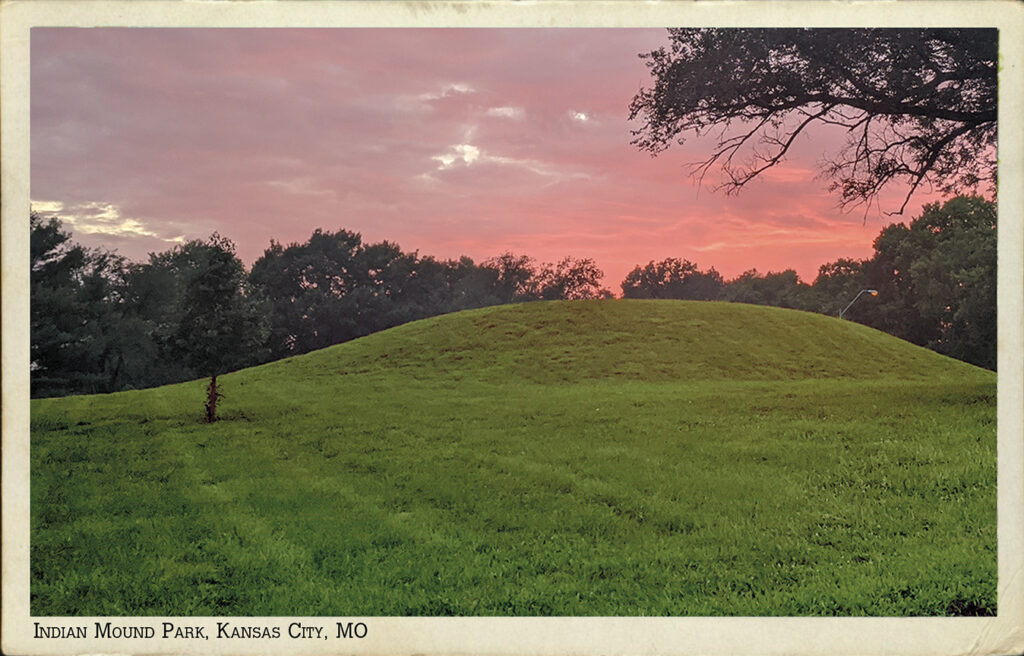

This week we’re shifting gears and coming back to our Historic Northeast roots with a profile of our own Indian Mound located at Gladstone and Belmont Boulevards.

We’re going to defer to a piece written by J.W. Chandler, President of the Kansas City, Mo., Archeology Society for a book published by the Northeast Optimist Club in 1983 entitled “Northeast Families / Communities, Kansas City, Mo. 1983.”

In 1884 Samuel King purchased land from the United States government. The high land overlooking the Missouri and Blue River valleys included an Indian mound. Years of neglect, picnickers, erosion and indiscriminate digging left only a faint resemblance of the former mound.

As early as 1877 the Kansas City Times reported a Judge Hunter and a group investigated two mounds on the Scarritt place and reported burials and burned stone hearths.

In 1923, Edward Butts, curator of the museum located in the public library, excavated what is now known as Indian Mound. Butts excavated four directions from the center of the mound. Each trench was 50 feet long and five feet deep. Butts reported finding arrow and spearheads, flint knives and stone grinding tools used for processing grain. He noted the soil used to construct the mound was foreign to the area.

The mound building period in North America began as early as 3000 BC with modest mounds covering shallow graves and reached its peak with the building of Monk’s Mound in Cahokia, Ill. which measured 98 feet high with a base of 16 acres. It was thought to have been constructed by the Mississippian people between 900 AD and 1100 AD.

Excavation of other mound sites has been conducted by the Smithsonian Museum in the Riverside and Parkville area, resulting in many Hopewell Mississippian artifacts being recovered.

After much indiscriminate amateur digging, the Northeast mound was re-sculptured in 1937 by the Parks Board working with the Works Progress Administration, reconstructing the mound back to what was thought to be the original shape and dimensions. The flat top and absence of any human remains would indicate a temple mound with some sort of structure on top.

Examination of pottery, projectile points and presence of charcoal could date the mound. However, the location had probably been visited and used by prehistoric peoples and various indigenous tribes such as the Osage or the Konza people for over 10,000 years.

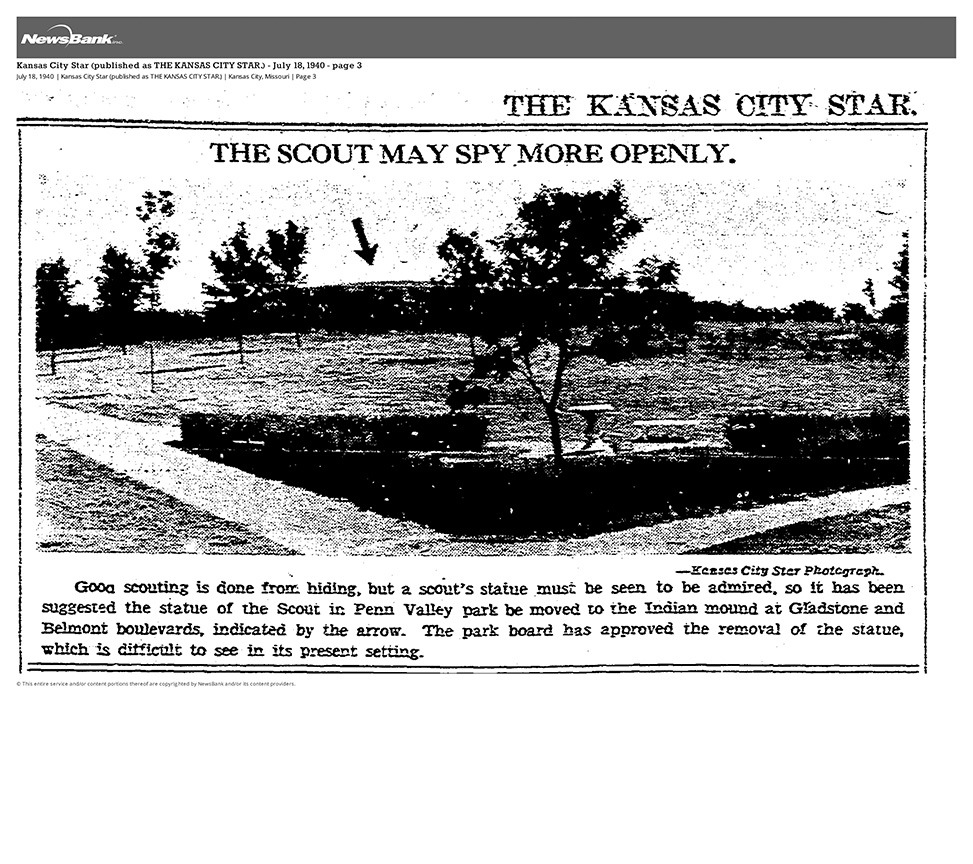

Interestingly, in 1940, the Parks Board passed a resolution to move the city’s Scout statue from Penn Valley Park to the Northeast Indian Mound. During a Wed., July 17, 1940 meeting, Parks Commissioners Moore, Peters and Chandler introduced a resolution to move the iconic Cyrus Dallin sculpted Scout statue because the Indian mound overlooking the Missouri River Valley would be a more fitting and realistic location for a statue of that nature.

Another reason was because North Terrace Park was lacking in ornamentation, having only the Colonnade at the Concourse and the Thomas Hart Benton memorial at Benton Boulevard and St. John Avenue, and Penn Valley Park already having a “cluster of statues and statuary within its confines.”

The move, according to a Kansas City Star article published on July 19, 1940 was to quell the vandalism that the statue was suffering at the time and the Northeast location would have been a more fitting and safer location. The Municipal Arts Commission never approved the resolution so The Scout statue stayed put in Penn Valley Park.