RobyLane Kelley

Editorial Intern

The Northeast community grabbed a slice of North American Hispanic history June 29 at the Kansas City Museum (3218 Gladstone Blvd.), with its Los Vaqueros Celebration. Vaqueros — the continent’s first cowboys — led many early cattle drives, among other tasks.

These cattle drives from Texas to Missouri and Kansas were vital to the growth of early cities and communities. This included cattle driven by early Hispanic peoples, or freed slaves from Texas to cities like Sedalia, Mo., and Abilene, Ks. The Kansas City Museum sought to honor the vaqueros legacy and and its impact on American and Kansas City development.

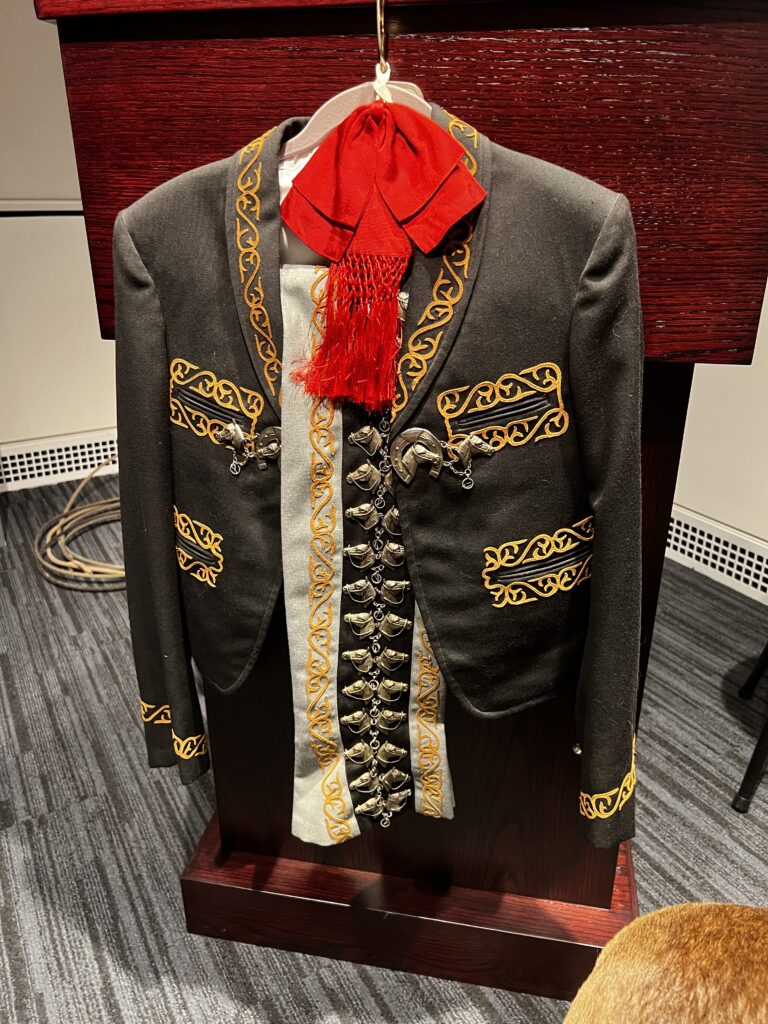

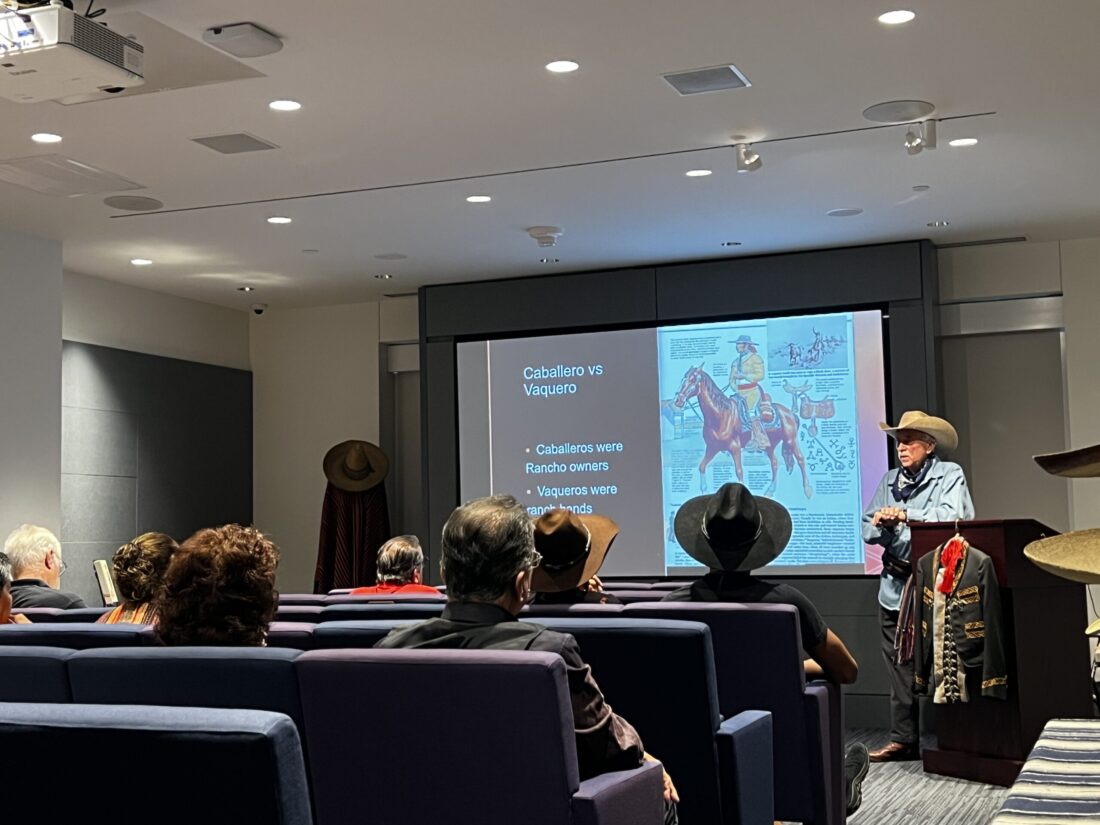

This free presentation event featured Historian in Residence Gene Chávez and Museum Collector Tony Florez. The room was filled with Florez’s lifelong collection of memorabilia and clothes, while attendees observed Chávez’s brief, yet detailed, overview of how America’s initial cowboys came to be.

“I have always been curious of the history of Kansas City,” Chávez said. “Specifically the Latino Mexican-American.”

Chávez said growing up, his grandmother lived near a ranch in New Mexico where he would watch the ranch hands bring in and brand cattle. Chávez grew up watching westerns — only his cowboys weren’t like John Wayne — they were Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete and Javier Solis.

According to Chávez, many traditions known to cowboys today found their start in Vaquero culture. The singing Hollywood cowboys follow the vaquero tradition of telling their stories through song, while they finish their day or on a cattle drive.

“The vaqueros developed the style of storytelling around a campfire singing corridos,” Chávez said.

Chávez referenced the late Dr. Jesus “Chuy” Negrete who — while working in Chicago — used the art of corridos for activist work. Corridos were used to tell a story and to bond vaqueros. Today that legacy carries on as musicians use it to rally for a similar cause or to mourn a lost loved one.

Vaquero culture is additionally found in the words we associate with the Wild West. Many of this vernacular stems from rodeos and ranchos. In Spanish, “la reata” translates to “the rope,” however the “cowboy” would be “lariat,” when referring to a rope used for lassoing cattle. Sombreros are another piece of vaquero culture adapted to Western history with traditions of their own.

“One of the favorite competitions of some of the vaqueros was to ride and lean down off of their horse while it’s running full speed and pluck off the head of a buried chicken,” Chávez said.

According to Chávez, the winner of this competition would win a gálon — the rope wrapped around the crown — for their hat. While a debated theory, some historians believe that when English speakers heard the word “gálon” as “gallon” it may have led to the term “ten-gallon hat.”

While sharing his history with sombreros, Flores dragged his spurs against the floor to make its iconic noise in presenting his collection. Like Chávez, Flores said he remembers watching Westerns while he was growing up.

When in Mexico as a child, Flores’ grandfather asked him what he would like to take home to the States. Flores said he wanted spurs and a proper black sombrero with silver detailing. He recalled walking around Mexico for the rest of the day, dragging his spurs like his favorite character from “Gunsmoke,” Festus Haggan. This sombrero and several of Flores’ spurs were on display.

The history of Kansas City is closely tied to the vaqueros, and the legacy of this Hispanic tradition lives on through the efforts of people like Chávez and Flores. While this presentation was a one-time occurrence, Chávez said he hopes to hold similar events in the future.

Chávez said it’s important for Northeast residents to “take pride in their history.” He said the vaqueros “provide a role model” and there are still ranches and rodeos continuing the tradition of the first cowboys across the country.

More Kansas City Museum events can be found on its events page or social media.