Daisy Garcia Montoya

Education Reporter

Progress remains stagnant months after the Kansas City Council passed Ordiance 240165 in February declaring the creation of the Office of Language Access.

The office — which would provide translation and interpretation services for those seeking city wide services or documents — is a result of a resolution passed by Mayor Pro Tempore and 5th District Councilwoman Ryana Parks-Shaw during summer 2023. This motion directed the City Manager to create a language access program. This resolution was followed by a community engagement campaign in fall 2023 — led by local organizations KC Tenants and Advocates for Immigrant Rights and Reconciliation (AIRR) — to gather data and provide guidance on this office development.

Once this ordinance passed in February, a budget of $900,000 was set with a minimum intention of four permanent staff members to fulfill the duties of this newly established office for 2024-2025. Nearing the six month mark since this office was approved by the city, its positions remain vacant.

Now, community members raise concerns on this program’s progress and quality following results of recent experiences with City-hosted events , which offered language access services.

“Es un poco complicado sabiendo que solo hablo español y sabiendo que estoy en un lugar donde se habla inglés, el acceso al idioma se vuelve fundamental para saber cómo caminar, cómo sobrevivir aquí en este mundo,” says Tomas Hernandez. (It’s a little complicated knowing that I only speak Spanish and knowing that I am in a place where they speak English. The access to language then becomes fundamental in order to know how to navigate and survive in this world.)

Hernandez shares that he attended the May 18 City Language Access Summit with hopes of providing feedback and learning more about the City’s ongoing efforts to bring language access to residents.

Instead, Herandez said he left feeling disappointed and with more longing due to his summit experience.

“Por ejemplo, llegamos al lugar y no sabía interactuar con la gente porque la primera persona, la persona que te registra, habla en inglés y entonces uno no encuentra la confianza para saber donde sentarme, donde ir y ni siquiera eso encontramos,” Hernandez dijo. “A mi me juntaron con una señora que era interpretadora que me iba a traducir a mi, pero la señora no sabia de que estaba enfocado el tema de la cumbre.” (For example, we arrived and we didn’t know how to interact with the people because the first person, the person who registers you in, speaks English and so one does not find themselves in trust to know where to sit down, where to go and we didn’t even find that,” Hernandez said. “They paired with me with a lady who was an interpreter who would interpret for me but she was unaware of the the topic of the summit.”)

Jaly Castillo, another participant, said she also had a similar experience.

“Todo nuestro equipo estuvo separado. Todos los que son impactados, estaban alrededor en el fondo. Los que hablan inglés en medio, y se supone que si eres impactado te tiene que dar una preferencia para que puedas comprender,” Castillo dijo. “Entonces ves la pantalla, en inglés. Nos meten a una plataforma, en inglés. Prácticamente no comprendemos nada y la traductora nos está hablando pero hay muchas voces y entonces se distorsiona.” (“Our entire team was separated. Everyone who was impacted, was spread around the room. Those who speak English were in the middle and it’s assumed that those who are impacted should have a preference so you can better understand,” Castillo said. “So then you see the screen, it’s in English. They make us use a platform, also in English. We practically did not understand anything and the translator would speak to us but there were so many voices that it would get distorted.”)

Castillo said that this experience differed from what she experienced during the City’s last budget hearing, which was held March 4, where through a partnership with KC Tenants and Councilwoman Bough’s office — interpreting services were offered to the community.

“Fue todo muy cómodo. Nos recibieron en español, nos explicaron la hojita, como se usaban los aparatos, nos acomodaron los aparatos y nos permitieron sentarnos donde sea, con nuestro equipo. Vamos a un lugar en la ciudad entonces necesitas sentirte en comunidad para sentirte segura,” dijo Castillo. “Se habló de muchas cosas, el presupuesto y comprendí todo de lo que se puede hablar en esas juntas. Que quede bien satisfecha con las traducciones.” (Everything was very comfortable. They welcomed us in Spanish, explained to us the materials, how to use the interpreting devices, fixed us the devices, and allowed us to sit wherever we wanted, with our team. We come to a City building, so you need to feel in the community to feel safe,” Castillo said. “They spoke about many things, the budget and I got a sense of understanding of what can be brought up during budget meetings. I felt satisfied with the translations.”)

Both Hernandez and Castillo said that after their negative experiences they had at this Language Access Summit, they were curious to see what the City’s preparation and quality in services would be like during the next public engagement event — the Mayor’s New Americans Commission Town Hall.

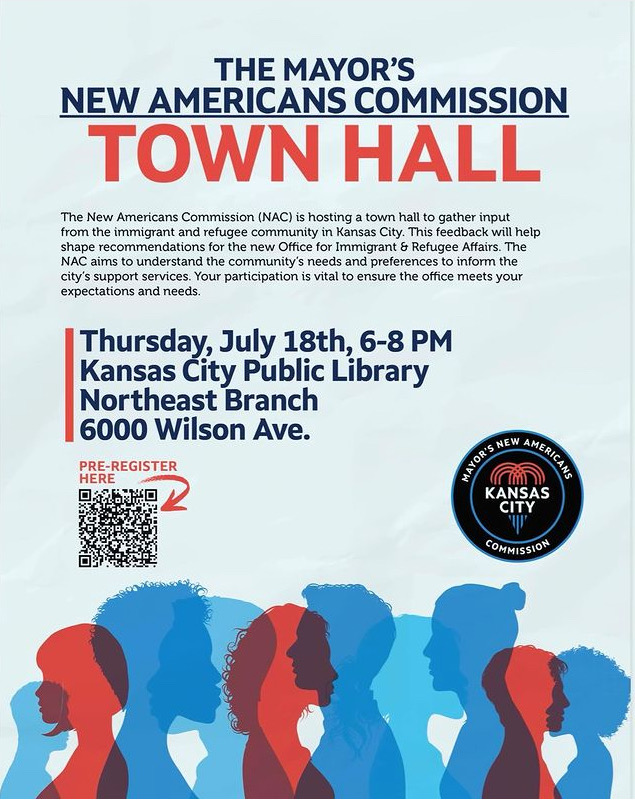

As they anticipated the Town Hall, their concerns grew after seeing the poorly translated media graphics used to promote this event. The Mayor’s New Americans Commission: Town Hall,” which read “La Nueva Comisión Americana Del Alcalde: La Alcadía,” creating two misinterpretation for Spanish-readers to understand it as “The Mayor’s New American Commission: Town hall.” First, the meaning that this Commission is for immigrants and refugees as new Americans is bungled due to the poor translation. In the second, had “alcaldía” been spelled correctly, “alcaldía” means the Mayor’s Office or City Hall (the physical building), it makes it difficult to distinguish that this is a town hall meeting.

Additionally, the QR code that was placed on the flier took scanners to an English-only registration form.

The town hall took place July 18 at Kansas City Public Library’s (KCPL)Northeast Branch as part of an effort to gather feedback on the community’s need for a new Office for Immigrants and Refugee Affairs.

During the townhall, community members were invited to share their testimonies to the commission. Hernandez and Castillo — who are both active members of AIRR and have long advocated for language access initiatives — attended this event, among other members of AIRR.

Castillo said upon arrival, she was received in English and noticed the interpreter was not at the same rhythm as the rest of the speakers. They also experienced technical errors with the interpretation device, which led Castillo and others to miss out on items discussed during the town hall due to lack of translations.

As this experience coincided with the Language Access Summit, Itzel Vargas Valenzuela — AIRR program coordinator — said she felt she couldn’t trust in the City to be prepared for interpreting testimonies and decided to help translate her team’s ahead of time to ensure that their testimony would be understood as it was intended to.

When Castillo went up to the podium to give her testimony, she found herself in an awkward situation when the interpreter told her to read her entire testimony in Spanish, so that the interpreter could then relay the message in English by reading the English translated version.

“Me senti muy incómoda porque ella me quería decir cómo leerlo. Tuve que hacer lo que ella quería que hiciera para que ella no me tradujera porque ella no me tradujo, ellos leyeron nuestros testimonios y es muy diferente traducir a leer. Me sentí muy mal porque quebró mi seguridad,” Castillo dijo. “Al final dije algo espontáneo que no estaba escrito y totalmente dijo otra cosa que no quería decir yo, lo tradujo mal. Lo que no teníamos preparados, lo que fue espontáneo no lo pudo traducir bien.” (I felt very uncomfortable because she wanted to tell me how I should read it. I had to do what she wanted only for her not to translate, because she didn’t translate, they read our testimonies and translating is very different from reading. I felt awful because they broke my confidence.”)

If it had not been for the prepared translated English testimonies, Vargas-Valenzuela said, their testimonies would not have been properly translated to convey the desired message.

In a room of nearly 60 people, only two individuals were part of this impacted community additionally needing language access services.

During the town hall, various testimonies mentioned the need for the City to seek guidance from local organizations that work with these impacted communities due to their existing relationships and expertise. It additionally addressed the need for language access to achieve community engagement properly as it seeks feedback for the new Office for Immigrant’s Refugee Affairs.

Community members also pointed at Mayor Quinton Lucas’s comments earlier this spring — where he welcomed migrants with work permits to Kansas City — as part of the reason local organizations remain overwhelmed without the proper systems and support from the City in place.

When this town hall wrapped up, the commissioners asked for grace and patience as they collected feedback and further developed the Office of Immigrants and Refugees.

As members of AIRR reflected on the town hall, they felt that although they expressed this need for language access to better inform the needs of the Office of Immigrants and Refugees — they did not feel satisfied the commissioners received the specific demands that will guide the City in the development of this office.

Additionally, the methodology in how the City posed questions during the Language Access Summit and Town Hall offered no background on City services nor provided information on what the City could offer, which led to broad questions and answers.

“When you ask a general question, you will receive a general response. For example, during the Language Access Summit, they asked what documents people need translated and obviously the people responded with all of them,” Vargas-Valenzuela said.

Although the Town Hall centered on the Office of Immigrants and Refugees, leaders of AIRR KC and other testimonies discussed the cross over between language access to get the engagement and participation needed to best guide this development of the Office of Immigrants and Refugees.

Vargas-Valenzuela said that since the Mayor made his comments regarding welcoming migrants to Kansas City, AIRR is persistently overwhelmed with outreach from migrants and asylum seekers trying to relocate to Kansas City.

“We are in crisis mode and we need language access. We need the Office of Immigrants and Refugees to be up and running,” Vargas-Valenzuela said. “If we talk about how long it has taken them to hire someone for the Language Access office, like we saw in the Town Hall, they are still not thinking about the hiring process for the Office of Immigrants and Refugees and it makes me think about what they are waiting on? What are they waiting for?”

The City posted applications for the Office of Language Access manager position July 15 on its website and plans to open its other positions once a manager is hired. For more information, visit: https://psweb.kcmo.org/psc/ps/MOBILE/MOBL/c/HRS_HRAM_FL.HRS_CG_SEARCH_FL.GBL?Page=HRS_APP_SCHJOB_FL&Action=U.