KCUR | By Mike Sherry, Celisa Calacal, Cody Boston, Julie Freijat

Kansas City’s Central City Economic Development program, started in 2017, is set to be renewed soon — but critics aren’t so sure about a program they say has done little.

If you walk down the hall of KD Academy, watch your step. A tyke might bolt from a room to hug the shins of the man who has come to pick him up.

Such a scene unfolded recently as Myron McCant led an afternoon tour of the early learning center he owns and operates with his wife. Featuring hallways painted in sky blue and bright yellow, and clean enough to pass even the most exacting white-glove test, the business serves as many as 150 children a day on Kansas City’s east side.

Yet the 24-hour facility that provides a crucial service for working parents almost never happened after six banks refused financing. The McCants’ lifeline came from $1 million awarded through Kansas City’s Central City Economic Development (CCED) program, financed by a one-eighth-cent sales tax that voters narrowly approved in 2017.

Those first-in dollars finally helped secure a bank loan. “It was everything,” McCant said of the CCED funding. “Without that $1 million grant from the city, we wouldn’t be here today.”

But the CCED tax is facing headwinds as the time approaches for backers to seek a renewal of the levy, which came with a 10-year sunset.

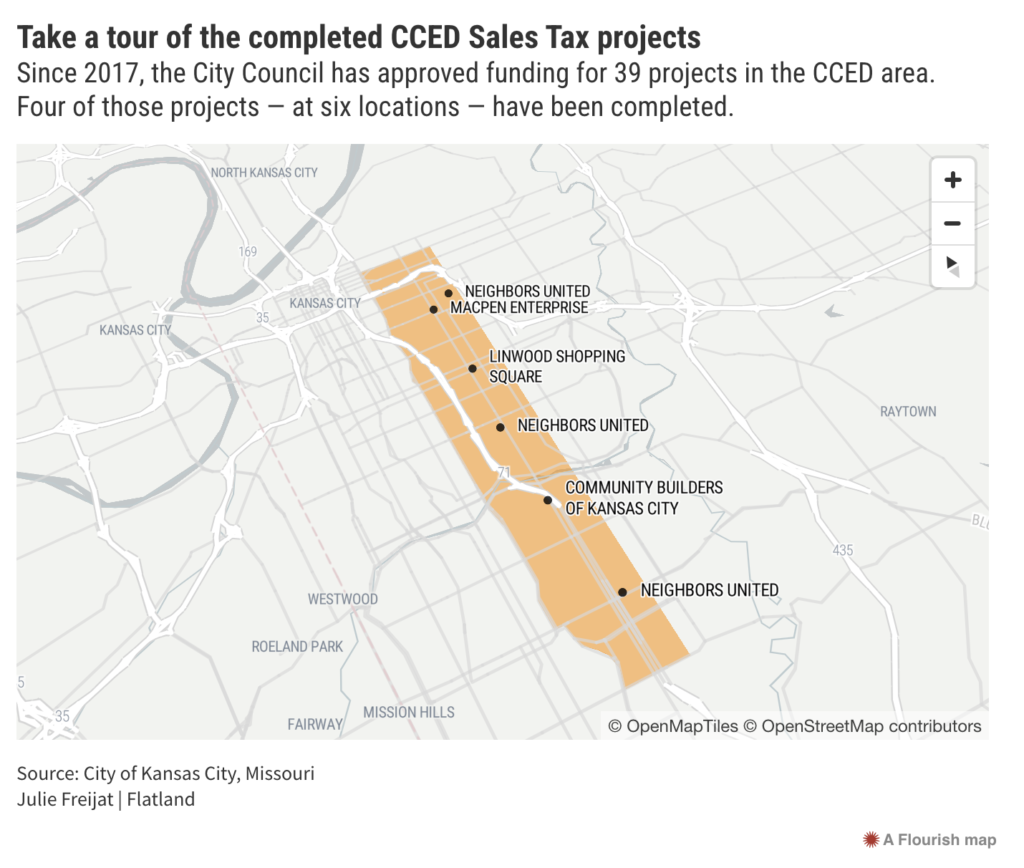

Critics like Gwendolyn Grant, CEO of the Urban League of Greater Kansas City, are questioning whether they would support renewal based on what they consider to be poor administration of a fund that counts just four projects completed in the span of six years. Outside of a few projects that are “probably laudable,” Grant said the program has been a “total failure.”

McCant and other defenders of the program said critics don’t understand the challenges of construction in general, or more specifically the even greater difficulties posed by developing on the long-neglected east side — especially in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Shepherding projects through the city’s development bureaucracy has proven to be one of the biggest hindrances to the program’s success. Tax proponents insisted the city must place representatives out in the community to ensure the long-term success of the program.

In Kelvin Simmons and Kenneth Bacchus, program supporters have in their camp two former councilmen with extensive economic development experience.

Simmons once led the Missouri Department of Economic Development and is co-owner of a mixed-use development in the 18th and Vine Historic District that has received CCED funds.

Bacchus is the board chair of Community Builders of Kansas City, a nonprofit urban core developer, and as a member of the economic development board that helps administer the CCED, he said the program is poised to make “significant advances” within the coming year.

Supporting a neglected part of Kansas City

The CCED tax supports projects in a defined district that covers a nine-square-mile area bounded by Ninth Street to the north, Gregory Boulevard to the south, The Paseo to the west, and Indiana Avenue to the east. The district was home to 19,528 residents with a median household income of $23,812, according to city data released after voters approved the tax.

Photo: Dominick Williams /Flatland

Backers purposely created a district bisected by Prospect Avenue. They hoped that CCED dollars would spur the revitalization of a thoroughfare they consider to be the spine of the Black community. KD Academy is located at 2141 Prospect Ave.

The Missouri state statute authorizing the tax requires that at least 20% of the CCED proceeds go toward preparatory work, such as land acquisition and street improvements. Other allowable uses of the tax proceeds include marketing and establishment of training programs to prepare workers for careers in advanced technology and other high-skill jobs. Under the statute, the economic development board on which Bacchus sits must have five members with representatives from the city, county and school district. Bacchus represents Kansas City Public Schools.

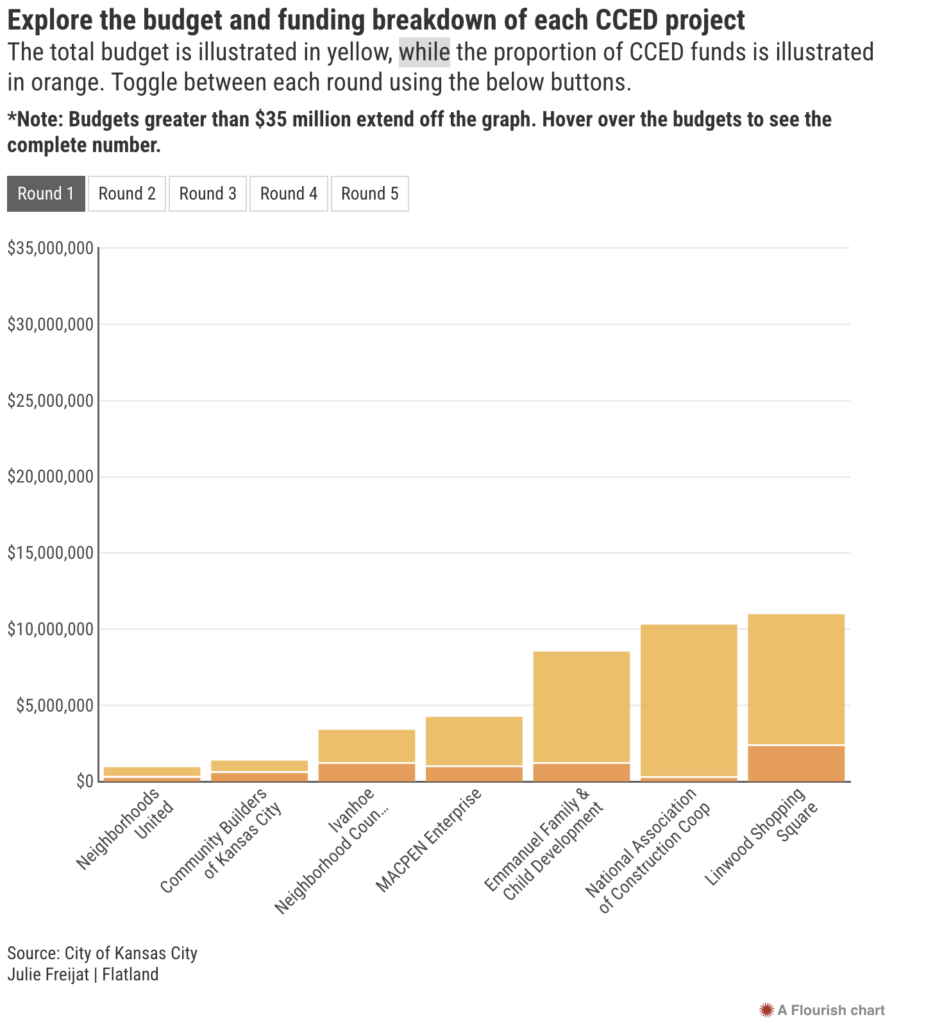

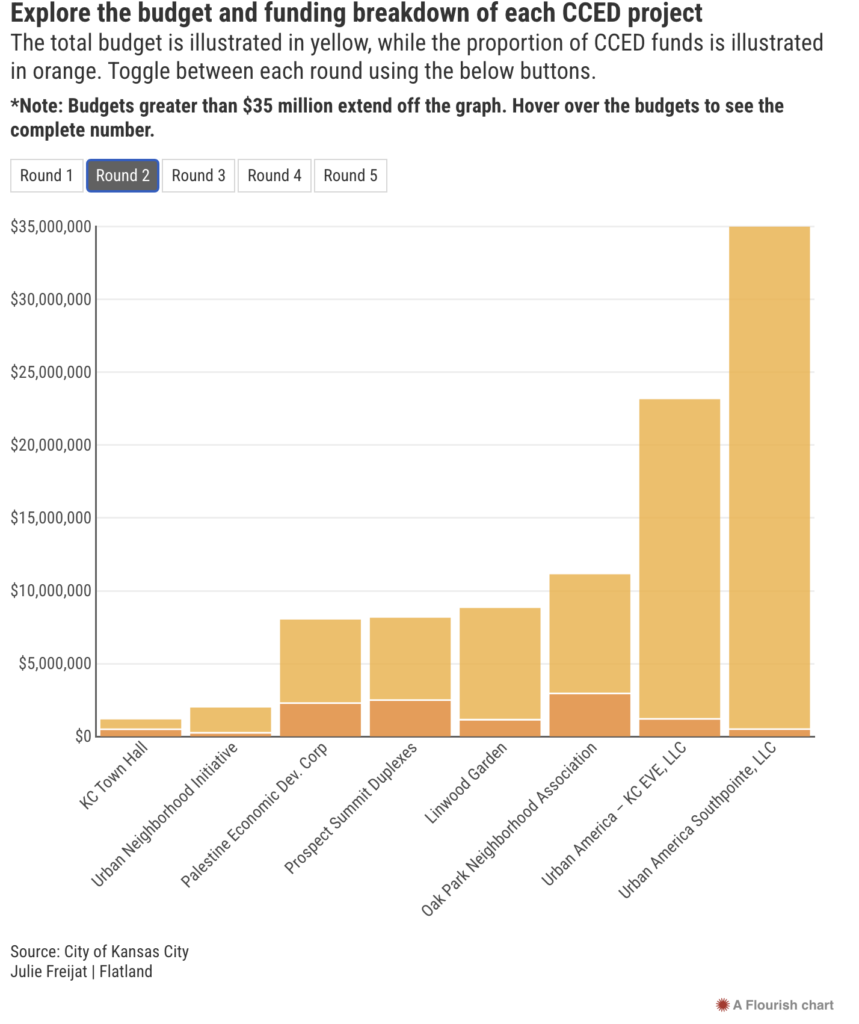

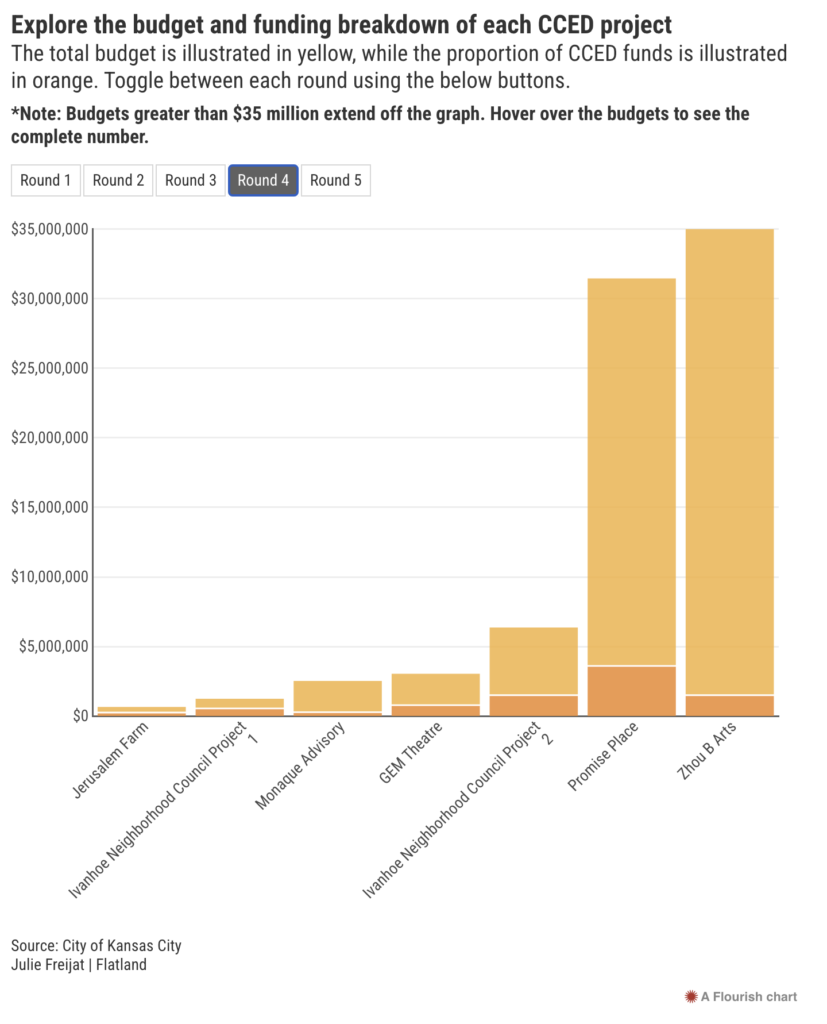

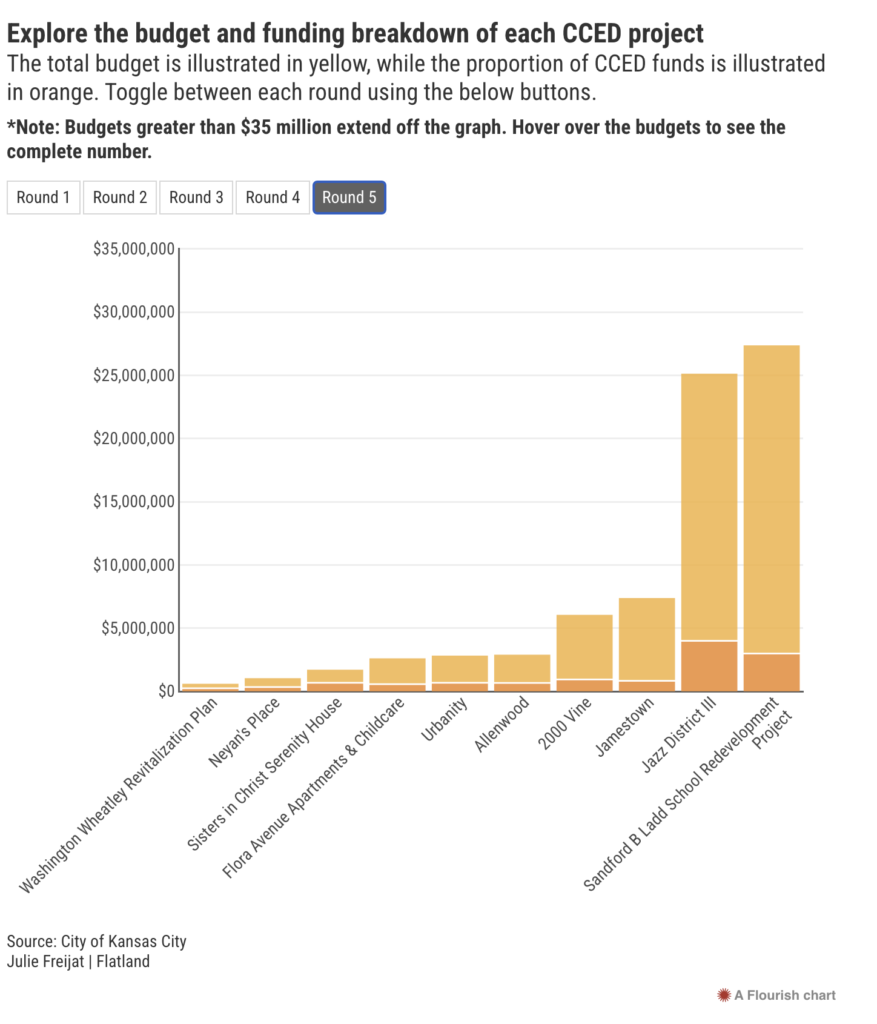

Revenue from the tax is coming in about a third higher than originally projected. The tax is expected to have brought in about $70 million by the end of this year, and the city council has allocated much of that toward the nearly 40 CCED projects it has approved.

Given the time it takes to negotiate and execute contracts, the city has only disbursed about 40% of the $53 million that has been authorized by the city council. About $20 million is available now for the next round of projects.

Community Builders of Kansas City received the largest single allocation from the fund — about $5.2 million toward its Offices at Overlook building along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Bacchus said he scrupulously avoided any involvement in discussions involving Community Builders proposals, a contention backed up by a former chair of the CCED board. Board minutes show that Bacchus recused himself from the vote on the Overlook building.

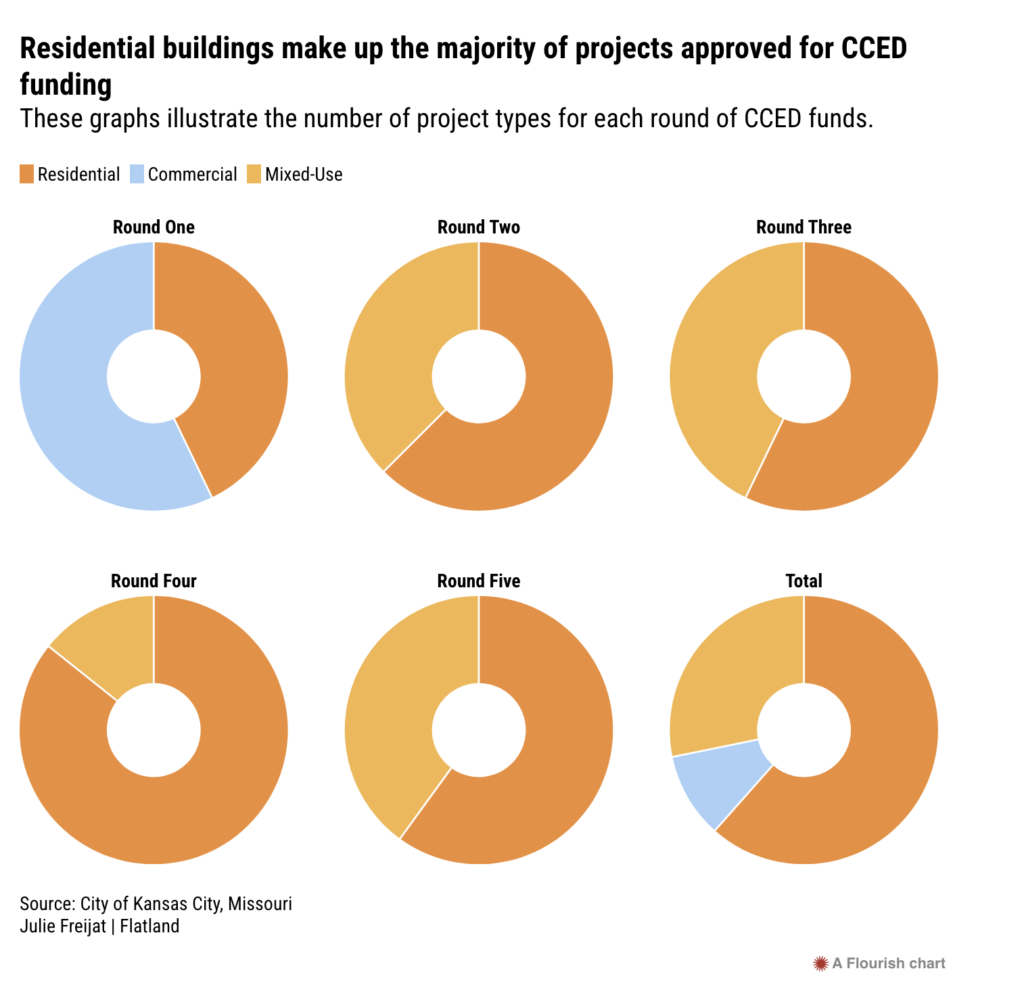

Other approved projects range from the rehabilitation of 50 residential units in the northern section of the district to a massive mixed-use development at 63rd Street and Prospect.

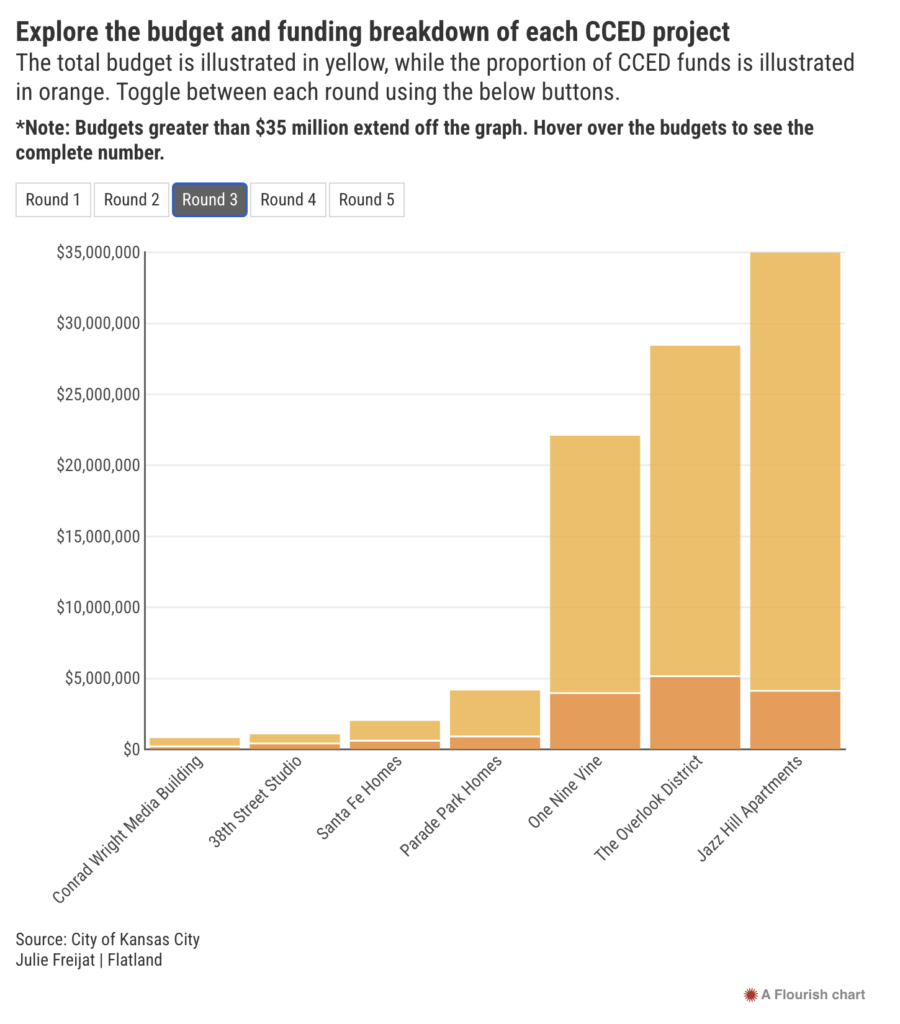

Simmons’ One Nine Vine project illustrates how a CCED project can make progress without being counted as completed in the city’s records. Simmons said the $26 million development at 1901 Vine St., which includes 80 residential units and seven ground-floor retail spaces, is about 95% complete. He received $3.9 million in CCED funding.

Calling it “one of the largest private development projects in the 18th and Vine area in modern-day history,” Simmons said it was “very unlikely this project would have taken place” without the CCED funds. The funds helped draw in private investors.

Ajia Morris is another beneficiary of CCED funds with a project in progress, receiving $3 million toward a $24.4 million redevelopment of the former Sanford B. Ladd School at 3640 Benton Blvd. Morris is rehabbing and expanding the building as co-founder of LocalCode Kansas City, a development company with a focus on projects on the east side. Part of the plan for the school is to make it a health, wellness, and beauty hub that will house minority practitioners.

Morris hopes to begin construction in the first half of next year. She said the CCED funding was integral to the Ladd project by relieving some of the burden of raising philanthropic dollars.

Developing on the east side can be a challenge, Bacchus said, given that it has some of the oldest properties in the city. He cited one CCED developer who had his project held up for 18 months as the title company tried to clear up a lien against 25 feet of ground in the middle of the property.

Simmons, too, said he had to unexpectedly spend $150,000 removing an underground diesel storage tank workers found at his site.

Mixed results

Yet the CCED dollars pale in comparison to the financial assistance regularly doled out by the various economic development agencies within the city. In one fell swoop, for instance, Port KC in July extended incentives worth nearly $11 million for a mixed-use apartment complex in well-to-do Waldo. Simmons also pointed to $800 million in financing Port KC recently dedicated to a portion of the Berkley Riverfront next to where the Kansas City Current is building a stadium for its women’s soccer team.

CCED backers said the tax is not meant to compete with the alphabet soup of city incentive agencies like the Planned Industrial Expansion Authority (PIEA) or the Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority (LCRA). Rather, backers said, the CCED tax has sought to leverage access to incentives on the East Side projects along with private capital.

As proof, Bacchus said that the $53 million in spending so far authorized through the fund has attracted another $480 million in outside dollars.

“I’ll take those numbers,” he said.

The way the CCED process works is that the board solicits development proposals and sends its recommendations to the city council for funding approval after vetting the submissions.

But the city council is not the last step. The Department of Housing and Community Development further vets the projects while negotiating and executing contracts with the developers. That system largely explains why developers have so far received less than half the money authorized by the city council and nearly $20 million remains unallocated to projects. Bacchus said City Hall is going slower than he would like to initiate a funding round for the unallocated dollars.

A year ago, City Auditor Douglas Jones announced his office would review the CCED program as it approached the midpoint of its 10-year authorization. The work came, his office said, as “some external and internal stakeholders have concerns about the slow progress of projects with approved funding.” The audit, released in August, gave the program mixed reviews based on its analysis of a 10-project sample.

While concluding that most projects the office reviewed were making progress, the audit flagged lapses in oversight and administration of the program. In its survey of eight developers, half cited city contracting requirements as a source of delay in their projects.

Moving projects through the approval pipeline has proven to be the biggest flashpoint in the debate over the success of the program so far. Critics like Grant point the finger at an ineffectual economic development board, lacking in real estate expertise, that wasted money on consultants that did not deliver the administrative and strategic planning services they were hired to provide.

City Hall defenders privately say that the slow pace of some approvals happened because the CCED board greenlit projects from novice developers who did not have some of the most basic paperwork in order to proceed with contracts.

The audit said that CCED board members overstepped their authority by meddling in contract negotiations. But board members countered that they were merely trying to move along a snail’s-pace process and making inquiries on behalf of awardees who could not get answers from city staff.

If prodding the bureaucracy is considered meddling, so be it, said Bacchus, adding “there’s going to be more until they make it work. … This is a community-driven initiative and it’s going to stay that way.”

Like Grant, Karen Curls was an early supporter of the tax and worked to get it passed.

Curls said CCED “kind of went off the rails” because members of the economic development board either dismissed or did not know that the tax was meant for smaller developers.

“We had commissioners, and also probably people within the city, that began to have their own notion of how this should work … that was not really in alignment with the (tax’s) purpose,” Curls said.

City Hall bureaucracy also comes in for a lot of criticism for what many consider a lack of administrative support for the CCED program. To Grant, the city should have appointed a well-qualified executive director who would help the economic development board operate according to a plan, set goals and measure success. “None of that was there,” she said.

The consultant did assist the board in completing a strategic plan in October 2020 to guide decision making through the tax’s sunset date.

In a series of questions submitted to Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas, Flatland asked him to address the perceived lack of administrative support from City Hall. His three-paragraph e-mail response did not directly answer the question, noting that, “Like all things, we always work each day to be our very best, striving to improve anywhere we can.”

He added that in his eight years of public service in Kansas City, he had watched the Port Authority and other agencies incentivize development downtown, on the riverfront, the Country Club Plaza and in south Kansas City.

“I appreciate their success,” he wrote. “No agency has matched the effectiveness of CCED on developing our East Side.”

In responding to some of the criticisms, Bacchus defended the consultant as someone who is “very good and has taken us a long way” and said the board consists of smart people of varied experience who bring different perspectives to the evaluations.

The board has spent far less on administration than it could have under the authorizing state statute, which allows for the economic development board to earmark up to 25% of the proceeds for administrative staff and facilities. The board has spent only about 1% of its proceeds on administrative services provided by the consultants.

Bacchus, too, said City Hall’s administration of the program left something to be desired in the early phases of the CCED program. But he said the board and the city staff have worked through the learning curve of the past years and are collaborating well. As evidence, he noted that four of the 10 projects the city council approved in May are already under contract. That is a much quicker pace than in previous rounds.

“The city has never been bought into this. They never cared anything about it,” Bacchus said. “They didn’t prioritize this the way they should have. But I think I think that’s going to change.”

One improvement that many observers would like to see would be to have the CCED have a bricks-and-mortar presence out in the community that could provide information and assistance to interested applicants.

The board is not blameless, Bacchus said. It has approved some projects for unproven developers that have not gone well, he said, but that was in accordance with strategic objectives to help small businesses and boost the employment base. Those missteps have generally involved relatively small amounts of money, such as $200,000 or $300,000, he said.

“The city has taken chances in some things and lost a lot more money than that,” Bacchus said.

Uncertain future

Like many others, Curls said all parties probably share some blame for a program that is not as far along as many would have hoped. But pointing fingers is not useful, she said. “I’m not big on trying to blame,” she said. “I think we need to identify where the holes in the dike are and plug up these holes.”

When the time comes to push for renewal, perhaps history will repeat itself.

When supporters went to voters the first time, it was after a lot of groundwork laid by the Urban Summit, a Black-led organization that holds an annual conference and meets regularly to discuss solutions to problems in the urban core. Bacchus was president of Urban Summit at one time.

Bucking opposition from City Hall — then-Mayor Sly James said the uses for the proposed tax were too vague — Urban Summit took the issue to the voters alongside Freedom Inc., the venerable political organization with decades of experience advancing African American causes at the ballot box. Another partner was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Greater Kansas City. Organizers pushed their effort as the “One City Campaign,” arguing that a rising tide on the East Side would lift boats throughout the city.

The tax ultimately passed with 52% of the vote, thanks to strong support in the Brookside corridor. The measure barely passed among voters within the proposed CCED district itself, and the question failed in the Northland.

Not one for suspense, Curls read a book at home rather than joining the election night watch party at the Freedom Inc. headquarters.

When news of the victory came, Curls recalled: “I was so happy that we had done something collectively. We had made something happen that hadn’t been done before.”

At this point, Grant does not think supporters have much of a case to present to voters a second time around. She said the campaign promised the community affordable housing, retail and safe recreational places for kids to play. “And we can’t back that up,” she said.

For his part, Mayor Lucas said he expected the sales tax to be renewed when the time comes.

Curls is hopeful as well. “I think it can be salvaged,” she said, “It’s got to be soon, but I think it can be.”

This story was co-published with Flatland, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.