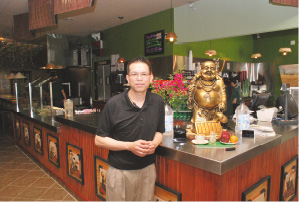

Above, owner Spike Nguyen stands in front of his newly finished restaurant, Pho Hoa Noodle Soup, 1447 Independence Ave. Pho Hoa held its grand opening June 10. Hours of operation are Sun. – Thurs. 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. and Fri. and Sat. 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Leslie Collins

By Leslie Collins

Northeast News

June 15, 2011

It wasn’t the quest for freedom or a better life that brought Spike Nguyen to America. It was simply an accident, an ornery streak in a little boy.

Dressed in a black polo shirt and khakis, Nguyen, now 39, sat in his newly opened Vietnamese restaurant, Pho Hoa Noodle Soup. Behind him, the cool, green walls oozed a sense of calm and tranquility – a stark contrast to his early childhood.

Nguyen grew up in Nha Trang, Viet Nam, a country ruled by communism and corruption.

As a nine-year-old boy, Nguyen didn’t fully grasp the concept. Living 25 feet away from the beach, he often swam with friends and snuck onto nearby boats, using the sides as diving boards. They were ornery. They were boys.

It wasn’t unusual when Nguyen scouted another boat to jump from one day. However, this time he was alone. As he stood on the fishing boat, he noticed a swarm of people swimming toward the boat. Frightened, he stayed put.

“When you’re nine and you get caught, you get whooped just like everybody else,” he said.

A whooping didn’t sound half bad once the gunshots began.

“The communists were chasing after us and the bullets were flying,” he said.

Despite the chaos, the fishing boat continued its journey, inching away from land until Nguyen’s home became a speck in the distance.

“I asked them where we were going and they said, ‘To America.’”

A total of 43 people were packed onto the 37-foot long fishing boat. Full of males ages 16 and up, Nguyen learned the boat was an escape – not only from Viet Nam, but from the brutal reality of war. The family who owned the boat had two sons who were drafted to fight in the communist-driven war against Cambodia. The family and their sons were fleeing, along with the sons of other Vietnamese.

“They had to leave the country that night and could only take what they could carry in their hands,” he said. “I’m one of the fortunate ones to be alive. Most of the people weren’t so lucky.”

At the time, the only way to flee Viet Nam was by boat. Many Vietnamese paid money to flee, heading toward Malaysia and Thailand. However, pirates infiltrated those regions and a number of Vietnamese were robbed, raped or kicked off the boat and abandoned, Nguyen said. In other cases, the dwindling supply of food and water killed the boat’s occupants.

For six days and nights, Nguyen lived on the cramped boat headed to the Philippines where the United Nations had set up camp for Vietnamese refugees.

“I was tortured by the sun,” he said. “There’s no shade and you’re on the deck. You get burned badly and in the evening you freeze because of the cold. The only thing I had was my swimming trunks. That’s all.”

For food, each occupant received a daily portion of rice slightly bigger than a stick of gum and two teaspoons of water at noon and in the evening.

“I wasn’t prepared. Nobody was prepared. They’d rather die trying to find freedom than stay back there and go to war,” he said.

At one point death seemed imminent.

As the sky darkened with menacing clouds, the sea slapped at their boat. Waves gained momentum, lurching higher and higher.

“At one point I almost got thrown overboard and had to grab the rope around me,” he said. “I was fearful.”

Terror spread like a disease and the boat’s occupants began to pray to God.

“You could hear they were chanting. They were praying. Even me,” he said. “We were hoping to be alive, that some miracle would happen. And eventually, the storm passed away.”

As the clouds lifted, they saw a glimpse of the Philippines.

“Everybody thought they saw a mirage. They didn’t believe it,” he said.

As the food and water supply became scarce, the boat drifted to shore just in time, Nguyen said.

Two weeks after living in the Philippines, another boat arrived with familiar faces from Nguyen’s hometown.

In disbelief, they looked at Nguyen and said, “You’re still alive! Your family put up a funeral at your home.”

Three weeks after Nguyen learned his parents thought he drowned, an American pastor who spoke Vietnamese offered Nguyen the chance to telegraph home to his family.

“We wrote letters back and forth. Having the middle child syndrome, you don’t know how much your parents love you,” he said.

Returning to Viet Nam wasn’t an option and for 2 ½ years, Nguyen lived in the Philippines, attending school, learning about American culture and the English language. For a bed, he slept on one constructed of bamboo.

“It’s curved, so when you sleep there, your back is aching. It’s not comfortable,” he said.

United Nations contacted Nguyen’s aunt and uncle, who lived in Houston, Texas, to begin the sponsorship process.

The Vietnamese refugees first landed in San Francisco, Calif., and received health inspections, he said.

“The first thing I saw was the Golden Gate Bridge. It was amazing,” Nguyen said.

For the first time in 2 ½ years, he slept on a real bed.

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God, this is heaven.’”

From San Francisco, he traveled to Houston to live with his aunt and uncle.

Although he felt homesick, he found comfort in staying with family members. Later, he graduated from a community college and moved to Shawnee, Kan., after a friend convinced him to work in the telecommunications field. For several years, he worked in telecommunications and later as a finance director at a car dealership, but knew his passion lied in the restaurant business.

“My whole life I wanted to be working for myself. It was my dream,” he said. “I love cooking. My kitchen at home is designed like the kitchen of a restaurant. We have multiple guests come on the weekends and I just cook for them. I enjoy serving people.

“Some people automatically have a heart for it, and I guess I’m one of them.”

Since January, Nguyen worked diligently remodeling the future Pho Hoa building, 1447 Independence Ave., Kansas City, Mo.

With Nguyen and his wife, Jessie’s input, an interior decorator transformed the building into a tranquil setting featuring artifacts from Viet Nam. Using a wood burning technique, an artist etched several scenes of Nguyen’s journey to America into a serving table. One scene depicts the fishing boat sailing through the raging storm with the inscription “Vietnamese refugees travel by boat.” The final scene shows the Statue of Liberty against the backdrop of the U.S. flag and the New York City skyline.

Asked why he chose Historic Northeast for his restaurant, Nguyen mentioned the substantial Asian and Vietnamese population in the area. Many have moved to the suburbs, but still return to the area to purchase Vietnamese ingredients.

“Plus, I like this area because there’s a mix of international races here and there’s a college right next door,” he said.

Although it’s a Vietnamese restaurant, Nguyen said he’s hoping a variety of nationalities will visit his business. Once Pho Hoa is more established, Nguyen said he’d like to open another restaurant in Northeast.

Nguyen’s restaurant features the Pho Hoa chain menu items and also a few of his own: the banh mi sandwiches, a family recipe featuring homemade butter, vegetables and meat grilled to perfection.

Looking back at the kitchen, Nguyen called his employees family and said his greatest satisfaction comes from the smile on his customer’s faces when they’ve finished their meal.

As Nguyen continued to talk about his restaurant, another customer walked in. The customer tried Vietnamese food for the first time in Nguyen’s restaurant and returned twice the next day. This time, he brought his daughter.

“Everything I’ve tried was wonderful,” the customer told Nguyen.

Several days later on June 10, Pho Hoa held its grand opening, complete with a ribbon cutting thanks to the Northeast Kansas City Chamber of Commerce.

As Nguyen stood by his wife holding the scissors in his hand, he fought back tears.

Nguyen is living the American dream, and this time, it’s not by accident.

Above, Surrounded by state and city leaders, Pho Hoa restaurant owner Spike Nguyen (center) and his wife, Jessie, cut the ribbon during the June 10 ribbon cutting ceremony. Below, the Nguyens display their collection of Vietnamese folded and rolled paper art. Photos by Leslie Collins