Northeast News Publisher Michael Bushnell sits down with Latino baseball player Mike Torrez. This conversation has been edited for clarity.

Michael Bushnell: The Smithsonian exhibit is opening up in our neighborhood tomorrow. So, this is pretty relevant to us given, we’ve got a roughly 40% Latino population that’s actively engaged in sports, whether that be soccer or baseball. So tell us a little bit about growing up in Topeka in the 1950s and how you got started playing ball.

Mike Torrez: Well I started playing, I was a bat boy from my dad’s – what they called back then – Cosmopolitan League. I had an older brother that played on the team, and Dad was the coach, and I was the bat boy. I kind of watched the guys, they were probably about three years older than I was, and I was always liking baseball. I always loved throwing stones and stuff growing up, and it was a lot of fun. That’s how I got started, and Dad kind of worked with me. We played catch when he came home from work, from Santa Fe Railroad, and we played catch for 10, 15 minutes at the most, and he’d get down and I’d sort of pitch to him, he’d give me a target. Maybe 25 pitches at the most. He kind of said, “Okay, that’s enough.” He gradually worked with me and didn’t overkill me. When I got tired I would get into a bad rhythm or just lose interest, but he always kept it interesting for me and had a lot of fun playing catch with him.

MB: What part of Topeka did you grow up in?

MT: Well I grew up in the Oakland area, and back then it was a Mexican community. A lot of the Mexican families lived there because a lot of the family’s fathers and grandfathers worked at Santa Fe Railroad there in Topeka. We grew up in Oakland and in our time, we played a lot with our neighborhood kids, maybe 15 to 20 kids around the neighborhood from all over would come over and we’d play softball. Every day, get up and go play softball. Always hit a few windows, break a few car windows and that would end the game. We’d all run home. We were gonna get it from our fathers or someone who’s grown, “Who broke the window?” No one ever lied, we just didn’t know who it was.

MB: The Oakland neighborhood kind of borders the Kaw River and downtown. Would you call it kind of a hardscrabble neighborhood, was it a good experience?

MT: Yeah, it was a great experience growing up. We always played, we went out early in the morning, we didn’t get back until the evening. It’s not like it is today, parents are scared to let their kids go out, I mean we used to go out all day. You never, ever, ever had to worry about somebody kidnapping us, nobody wanted us nasty old kids. We never worried. The only time we came home was when we were hungry to get something to eat. If it was for lunch to grab a little bite and then go back out and play again, all the rest of the afternoon. At Ripley Park they had a swimming pool there where on hot summer days we would go and swim all afternoon. We’d walk over to from Oakland to Ripley Park, which was what they call the bottoms area. Ripley Park was a ballpark where the Negro Leagues played back then. I can remember we used to go see them play, and it was a ballpark right by the railroad there. It was a great little ballpark and I saw a lot of games growing up there, older guys that were playing baseball, and always in my mind I wanted to play baseball, and that’s what I did.

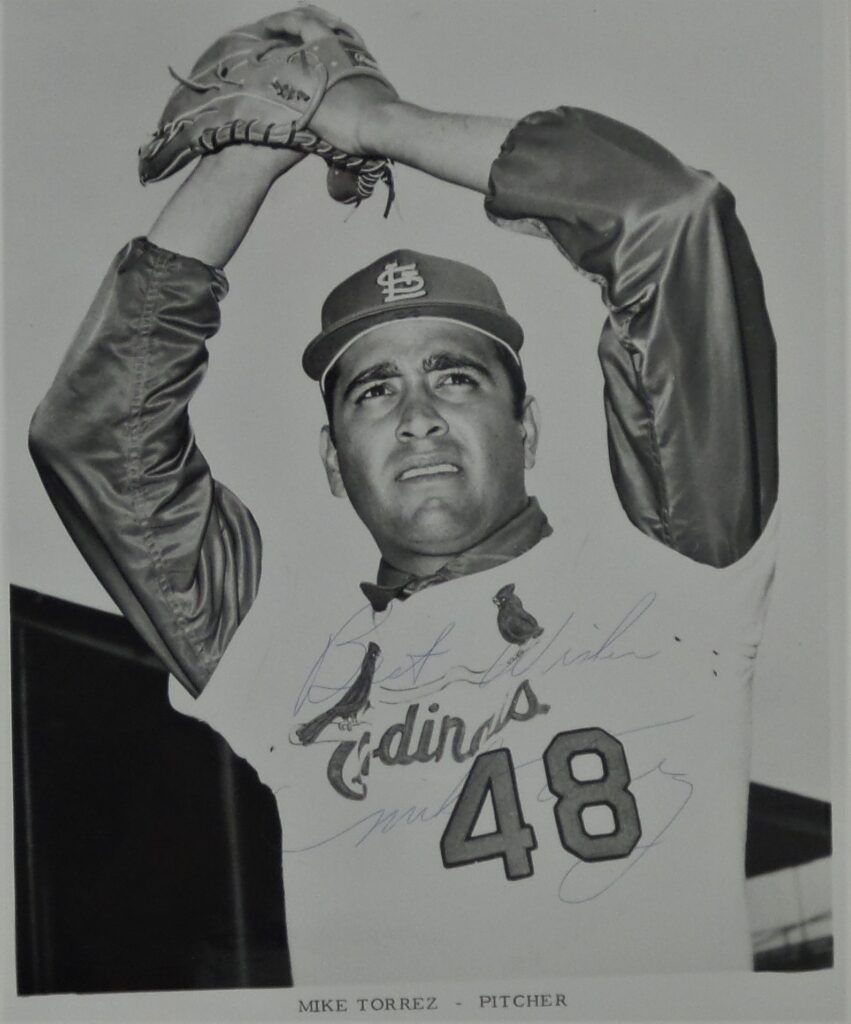

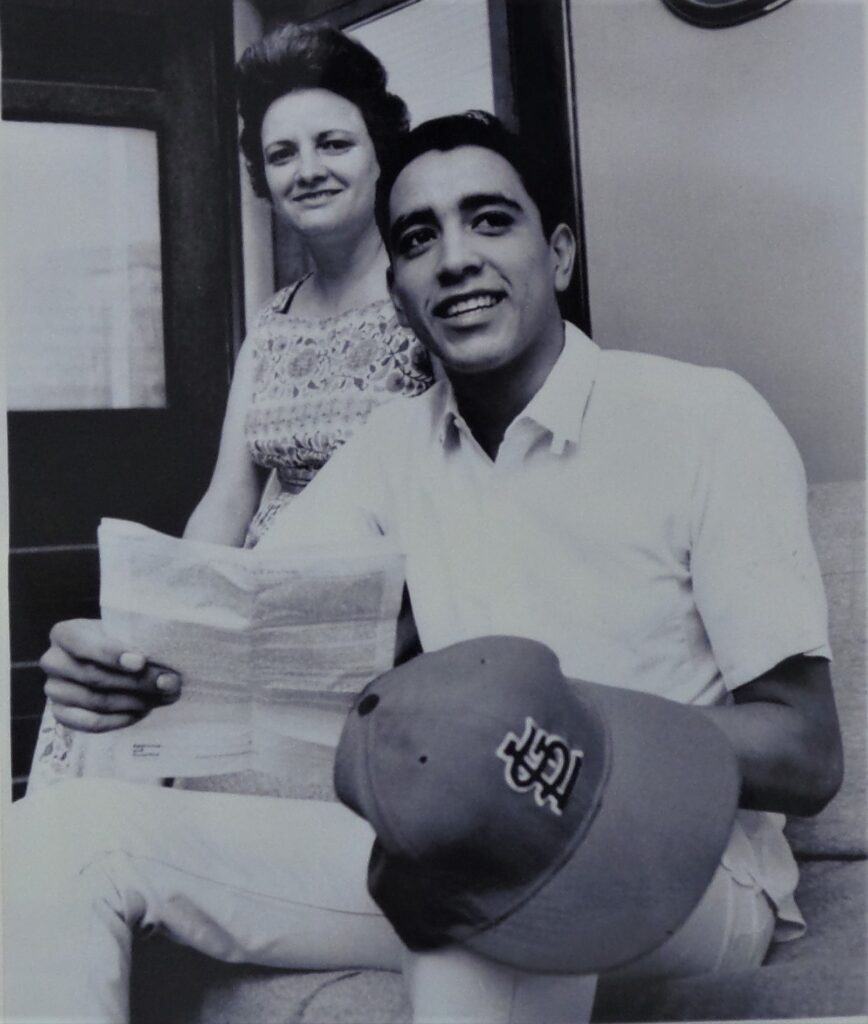

MB: You came up through Topeka High School and the American Legion leagues and then you were drafted as an 18-year-old in 1964.

MT: September the 10th, 1964 by the St. Louis Cardinals. But let me tell you something, which may have saved my arm and, maybe, possibly my career, because when I got into Topeka High School, they had just stopped the baseball program, and I never knew why. They were big in track and also in swimming, and for some reason for the three years that I was in high school, we never had a high school baseball team, and possibly that could have saved me because I know that I would have been probably pitching a lot. In American Legion ball, honestly I didn’t pitch until my senior year because the first two years in American Legion there was a kid by the name of Mike Griffin, his father was the coach, and Mike ended up getting a scholarship going to Arizona State. He was a left handed pitcher, but his father would always pitch him in all the big games, showcasing him.

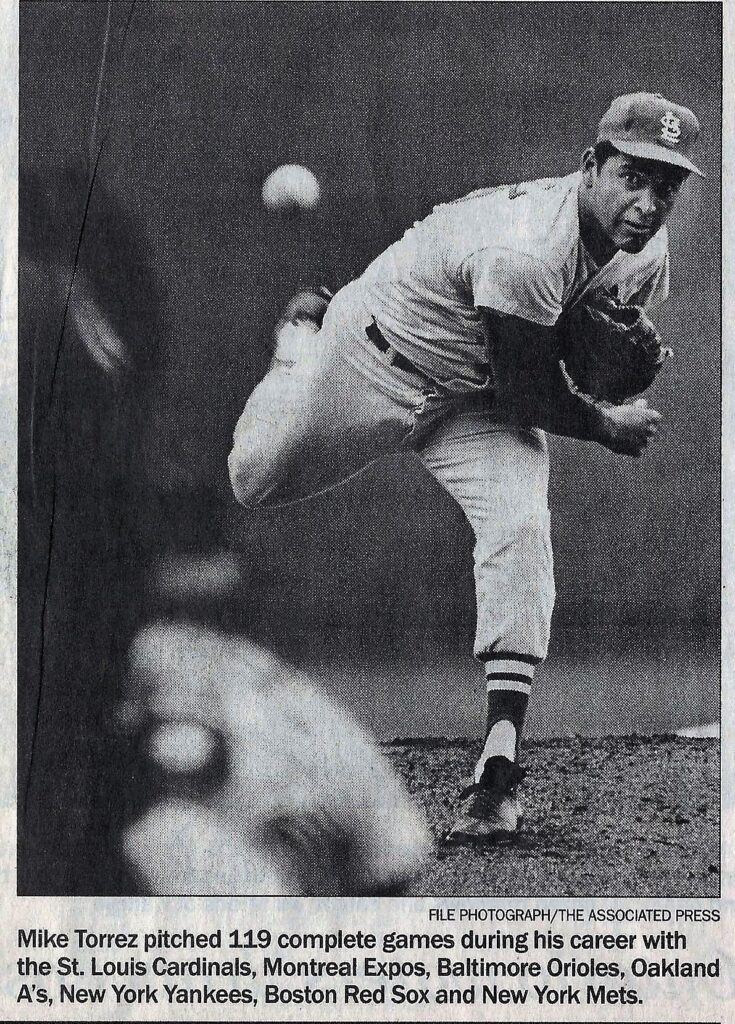

I used to come home and my dad would ask me, “Michael, you pitch today?” I’d go, “No.” He’d ask, “Then why the hell are you there?” and I’d say Mr. Griffin was pitching Mike all the time. My senior year Mike had graduated, he was a year older than I was, went to Arizona State, and then a new coach took on the American Legion managing job, and he told me, “You’re gonna be my main pitcher this year, so let’s have fun,” and I said okay. So, he pitched me and we only played back then like 15,16 games. We didn’t play a whole slew of games like they do today with these kids. But I think that saved my arm. I was able to get bigger and a little bit stronger and built up the right way, I guess, and I had a long career. I pitched 20 years professionally, 18 in the major leagues.

MB: And that first year with the Cardinals, they put you into what was kind of like a training school in Florida?

MT: I went to Hollywood, Florida, for the Winter Instructional League, and that was where a lot of the guys that maybe got hurt – double A or triple A – because there were players some double a triple A they came to the winter program that the Cardinals had back then. There were games that we played and it was funny because Steve Carlton was there, just signed, he signed out of one of the Miami schools, a junior college. He and I were there, a number of other players. There were a number of big players that were there rehabbing. That was in the winter of ‘64.

MB: What was it like for an 18-year-old kid being thrust into that, in the major league system? I would imagine back then it was probably pretty regulated and here you are 18 years old, and there’s somebody like Ron Guidry or somebody like that, what was it like for you coming up at it to peek into an experience like that?

MT: It was something I wasn’t used to. When we’re at home during American Legion, you could sleep all day and then go and play in the afternoon. Once you got into pro ball, it was a real awakening because you had to get up like around six o’clock because you eat breakfast and go to the stadium, in the stadium all day for seven days a week. It was no off days or anything, I mean, it was all day. Back then, they probably had 100 guys that were there at this camp and they would separate all the guys to go to different fields and do all these fundamentals all day, it was unbelievable. The Cardinals were big at teaching you fundamentals. If you were a pitcher you learned to bunt, practice swinging, hit the ball. I love hitting because I was getting to be a pretty decent hitting pitcher. But that was all day. It was a rude awakening because I never was used to that. Now I’ll tell you, talk about soreness, so sore you come home after practice, you didn’t want to go anywhere, just wanted to go lay down in bed, and just crash.

It was a seven-day-a-week deal, every day, every day. Repetition, repetition, repetition. But we had great coaches back then, the Cardinals organization. That’s why they’ve always been successful, I believe, they’ve always taught good, fundamental baseball. Back then, there was hitting runs, you’d play one-run games, two-to-one games. Today there’s nothing. There’s guys that don’t even hit and run, they don’t know how to put the bat on the ball with two strikes on. It’s either a home run, or swing or strike out anymore today.

MB: What you’re saying is back then it was just to get the base hit? It’s all about the base hit.

MT: Yeah, guys need to make contact, get the bat on the ball. Today, watching Major League hitters, they don’t know how to make contact with two strikes. They’re swinging from their heels and either they’re striking out or trying to get a home run, it’s unbelievable.

MB: So you played for a number of major league teams including the Boston Red Sox and the Expos, and of course the Cardinals. Walk us through a typical day in the life of a major leaguer when you were up to the big show.

MT: Get up at home, have your normal breakfast, wait – this is when we’re at home – go to the ballpark around two o’clock. Traffic sometimes, but get there say 2:30, have a soda, get ready, because a lot of times we had to get on the field around 4:30, we’d be out there shagging balls for the hitters and everything. The home team would hit first, and then, we get off the field to let the visiting team hit. On the road, we’d gone to stay in a hotel where you get your butt up and eat breakfast and then a lot of times you’d sleep in until like 10, 11, then you get up, maybe bypass breakfast and you go have lunch. There was always a bus that left like three hours before game time to get to the stadium, then we’d get to the stadium and get dressed and then we’d go on the field to have batting practice. The pitchers, like myself, we’d go out and shag for the hitters, and it was repetition. That was basically how everything was every game, whether we were traveling or not.

MB: This exhibit that is part of the Smithsonian is going to be a big deal. They’ve got the 18th and Vine Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, but there’s a couple of brand new baseball fields down there that are used primarily by junior college kids. There’s going to be games tomorrow, that’s kind of a big thing for the Latinos in Baseball program. What are your thoughts on that and how that developed, and how that’s being showcased now and the Latino baseball history starting to come to the forefront?

MT: Gene Chavez, who started this, has done a wonderful job and he’s gotten together with the Kansas City Museum and the exhibit and all that, and I’m so happy that he has started something like that to keep the Latino kids involved in baseball in the Kansas City area. You need that because there was nothing really going on with any of this. Latinos have always been kind of quiet and not really try to push to make things better for the kids as they’re growing up. Gene, when I’ve talked to him a number of times, he’s so interested in trying to get the Latino kids in the neighborhood that can’t afford to play baseball, and wants them to play baseball. Baseball is a great, great sport, don’t need much, but when you’re growing up a glove, some tennis shoes and the bat, everything is furnished anyway as far as equipment goes. I’m just happy that they’re doing it and it’s making people aware that, “Hey, there’s opportunity out there.” You just have to really go for it and believe in yourself and go do it.

MB: Growing up in Topeka, did you ever play – in the American Legion or some of the other leagues – did you ever play any of those Latino teams from Kansas City’s West Side?

MT: No, back then they only had softball. My brother and them played softball. And they were big in the fast pitch, but no I never saw any of them playing back then. I never knew of any of the Latino teams in the Kansas City area. I grew up just in Topeka, never really did a lot of traveling. I knew they had a lot of softball teams. Did they have hardball teams?

MB: There were a few. Being over here on the northeast part of the city, it was an Italian enclave back then and three-two baseball was big here. So we’ve got a lot of guys, one guy in particular, that came up through the Dodger system, and played a couple of years in their minor league system, his name is Moe Lago. He was really active in the three-two leagues over here in Northeast, but they had a whole separate deal on Kansas City’s Westside with the Latino softball and baseball teams. That’s the exhibit that Gene curated at the Kansas City Museum here a couple years ago that was real, real good and he got a lot of people to come out and a lot of families to share some of their history for that exhibit.

MT: I see some old photos, it’s really funny, my dad and then my uncle played baseball and they had a Mexican team back then. And they wore the old uniforms and that’s pretty cool. My uncle was a pitcher, he said, “Michael, I hurt my arm. Don’t throw curveballs until you get a little bit older, like in high school. I started throwing curveballs at a really young age and I ended up hurting my arm and I never was the same after that.” He always reminded me don’t throw curveballs until you get older, like in the senior year in high school, and I never did. I never did and I listened to him.

MB: Well you had a slider that even Hank Aaron commented on, didn’t you?

MT: Yeah, Bob Gibson taught me that slider when I was with the Cardinals. When I started to pitch, I didn’t have a slider. Gibby lockered right next to me and I looked at him and said, “Gibby…” and he looked at me like, “Hey, what do you want?” “Would you show me how you do that slider?” and he looked at me and he said, “Yeah, man. I’ll tell you what, you get your ass out here at three o’clock tomorrow. And don’t be out here and if you’re not out here,” he said, really pissed off. I said, “No! No! No! I’ll be here, I’ll be here.”

So, the next day I get there we go out and we start on the slider and he showed me how to grip it, how to start. And we started maybe about 20 feet back, didn’t go the distance. We just started little by little backing up, backing up, so that way I could learn to see the rotation of the ball. That’s how I learned his slider, and I did have a really good slider, I mean, that was an additional pitch that I had besides the fastball changeup. When I won 20 games in ‘75 with the Baltimore Orioles, George Bamberger worked with me on my curveball, and I think that made it even better for me because I ended up having a pretty decent curveball. A lot of teams early in my career didn’t realize that I came up with that. That helped me in the World Series, too. I know the Dodgers, when I was in the American League, I know they didn’t remember me ever throwing a curveball, so a lot of my strikeouts were curveballs in that ‘77 World Series.

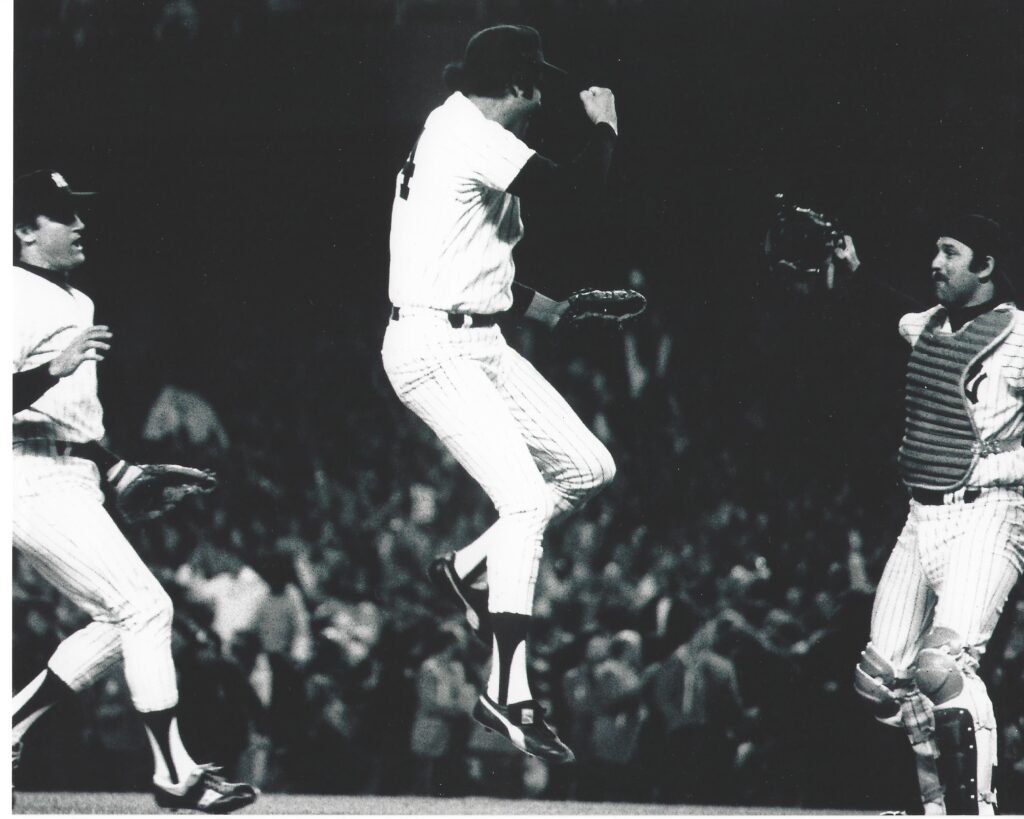

MB: What was your most memorable experience being a part of that World Series winning team in ‘77?

MT: I came in relief in the fifth game against the Royals in Kansas City. Ron Guidry started it, and we were down already, like by three runs or four runs early, in the first couple innings. Cloyd Boyer, the bullpen coach, said, “Mike, get up! We’ve gotten in trouble in the second inning.” Well hell, I’ve just got up and I swear to God, I only do like six or seven pitches, warming up in the bullpen – I knew I needed nine more before I faced the hitter – and here comes Billy Martin back back out and I’m gone. You gotta be kidding me. I think I ran the fastest 100 yard dash anybody ever ran just to get my blood circulating, my body going.

I got there and I did the pitches and thought, “Bases loaded, shit.” I got out of it, two strikeouts and the pop-up, and they didn’t score any more runs for about six and a third innings off me. I held Kansas City and thought if I don’t hold Kansas City, without them scoring, we’re never in the World Series. I look back, if I didn’t pitch the way I did in the fifth game of the playoffs against the Royals, we would never have made the ‘77 World Series, And there never would have been a Reggie Jackson hitting three home runs as MVP. And I should have been called MVP that year, I pitched two complete games in the World Series. So no one’s really done that ever but maybe one guy – myself. Pitching two complete games, and I caught the last out of the ‘77 World Series and that was great, just the feeling of winning and knowing I got my team to be in a World Series. That was my highlight of what I look back on. Every kid wants to get into the World Series, but I had a big, big part of it. Of course I broke a lot of hearts in Kansas City and a lot of my high school friends were Kansas City Royals fans. I got a lot of kidding from it, but they were happy for me.

MB: I do remember the 77 series because that’s my first year in college and everybody in the dorms at Missouri Western was watching those games. What kind of advice would you give to urban kids today growing up in regards to your experiences in organized sports, how it helped you and kind of propelled you up into the major leagues for 20 years?

MT: First of all, and I’ll be honest, you got to have talent, you got to have some talent to be a baseball player and I think God gave me the talent. I just loved it and I loved practicing. I was practicing not knowing I loved it, and it’s one of those deals where I just love to get on the field, and the kids have to believe in their heart that that’s what they want to do, because baseball is tough. It’s a tough sport, it’s an individual game, and your mind and your heart gotta love baseball, you got to sleep with the baseball. You gotta want it, it’s just like anything else. If a person wants it and if you have the talent, you definitely can make it. But you gotta want to, you gotta work hard at it, you gotta be dedicated to it. And sleep and talk baseball, that’s what you got to do, and you just gotta honestly have the talent as well, the God-given gift.

MB: We’ve talked a little bit about this in regards to growing up in Topeka and some of the systems you grew up with versus today, and parents are just like, “I’ve got to get my kid exposed,” it’s almost like it’s rabid – what advice would you give parents today?

MT: The kid’s trying his heart out, first of all, a young kid that is just playing, and a parent should never downgrade the kid if he makes a mistake. I mean, life is mistakes anyway, so you just say, “You tried your best. Whatever mistake you made, just try to remember why or how it happened, and just try to improve it, or try to say to yourself, ‘Okay, I’m not going to make that same mistake again.’” And that’s what it’s all about. Parents, you just got to live with the kid, make him happy – my parents never hollered at me that I had to do this, be this way, you gotta do it this way – they made sure to let me do what I had to do myself and they gave me encouragement, they were never negative towards me and made it fun. Make it fun for your kids, make it a fun thing. I believe that that’s the way it has to be, a lot of parents get on their kids that they messed up in the game, and then that kid, right then and there, just didn’t want to play anymore, they quit. Don’t even worry about it, just have fun and try to do your best. “We’re proud of you, no matter what.”

MT: I want to wish everybody success with the exhibit, and I’m looking forward to it. I’m just going to come in probably within a month and come in and see that.