After recent inquiries into the status of potential budget shortfalls, Kansas City Police Chief Rick Smith said in a blog post Wednesday that if the department is asked to cut additional funds for fiscal year 2021-22, it would result in police stations closing and a reduction in services.

“We are already doing our part to help in these tough economic times,” Smith wrote. “We’ve cut $5.6 million from the current fiscal year’s budget this summer.”

The City Finance Department requested that all city departments work out what an 11% budget cut would look like for fiscal year 2021-22. The city’s new fiscal year begins May 1, 2021.

“That’s nearly $26 million for us,” Smith wrote. “To make that number, we would have to reduce about 400 employees, and the remainder would have to take two-week furloughs.”

Smith said that could have an effect on anyone who visits, lives or works in Kansas City.

If faced with an 11% budget reduction, the department would propose consolidating the North Patrol Division with the Shoal Creek Patrol Division and the Central Patrol Division with the East Patrol Division.

North Patrol currently serves 67,600 people across 84.8 square miles, and Central Patrol serves 62,300 people across 17 square miles.

The department would also propose eliminating the Helicopter Unit, a Traffic Enforcement Squad, Community Interaction Officers (CIO), School Resource Officers (SRO), Police Athletic League (PAL), (CAN) Centers, social workers and a majority of Impact Squad officers, who proactively address crime.

Smith said if that were the case, all of those officers would be reassigned to patrol and answering 911 calls.

The department would implement a hiring freeze and not hold any Police Academy classes in 2020 or 2021. Smith said the department would lose more than 120 officers through this.

“No new hires means no additional way to have staff who reflect the community,” Smith said. “The Academy class we already cut this year was set to be our most diverse ever.”

The department would also reduce Property Crimes detectives and make a reduction of 13 people at the Kansas City Regional Crime Lab, as well as eliminating numerous support staff positions in areas ranging from information technology to fleet operations. Smith said this would result in a backlog in the Crime Lab that will slow the ability to solve cases.

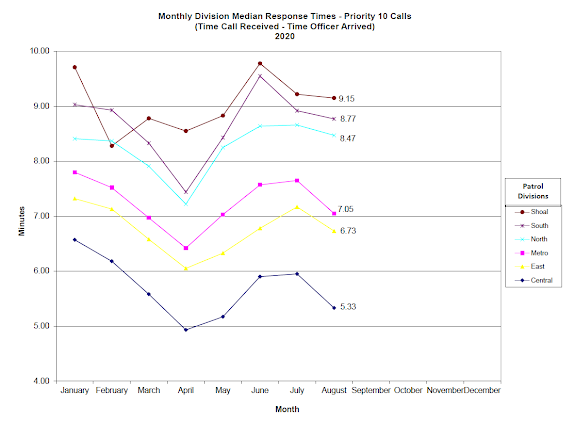

Smith said this means that when people call 911, they will likely be put on hold and response times will be at minimum 11% longer, especially north of the river and in the southland.

If someone does report a crime, Smith said there will be fewer detectives to investigate, and services may be diminished.

“We will have to prioritize response to violent crime,” Smith said. “It’s highly likely we will have to stop responding to non-injury crashes, car and home break-ins and other property crimes. Victims would be asked to report those to police stations themselves. Only the property crimes with [the] greatest losses would be investigated.”

Smith said positions that focus on community policing would be the first to go to focus on the department’s core mission of answering 911 calls and investigating violent crime.

“The people who need police service the most are our most economically disadvantaged,” Smith said. “They’re who call 911 the most and have the least resources. They are who our social workers assist. They are who will be hurt most by cuts to the police department.”

Next, Smith said all youth programming would be eliminated, like the PAL Center at 1801 White Ave., which is funded by a 501c3 that invests $500,000 annually into the urban core.

Smith said that reduced Internal Affairs detectives could impact officer accountability.

“Our community already has stepped up over the years to provide funding for equipment needed to solve and prevent crime and enhance officer accountability, such as license-plate readers, body-worn cameras and ballistic helmets,” Smith said. “What does this mean for all of their contributions?”

The last time the department faced a major budget cut was in 2008, and Smith said it took the department 10 years to come close to regaining the staffing they had then.

“It takes about a year and a half to recruit, process, hire and train a new police officer on our department,” Smith said. “We had more than 1,400 officer positions prior to 2008. We’re now at a little more than 1,300.”

The reductions would put the department at less than 1,000 officers, which last occurred in the 1970s. After the passage of the 1% earnings tax in 1971, the department hired 200 more officers.

“Does Kansas City really want to go backward 50 years?” Smith asked.

He noted the unprecedented increase in violent crime in 2020 and suggested that a reduced law enforcement presence and reduced investigations would change that for the worse.

Smith made note of the reforms that have been implemented at the request of the public such as body-worn cameras, an outside agency investigating officer-involved shootings, and policy changes.

The policy changes include explicitly stating the duty for officers to intervene in an excessive-force situation and revising department tactics during protests.

In addition to the $5.6 million cut from the current fiscal year budget, the department eliminated 90 positions and canceled all Academy classes due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Just like many families have had to do in the past six months, we’ve had to prioritize our budget,” Smith said. “That is something the Kansas City government must do now. In the most recent Citizen Satisfaction Survey, residents placed police services as their No. 2 funding priority, just below street and sidewalk infrastructure.”

The department has faced criticism recently as protests against police brutality have persisted across the nation. Demands have been made by protesters to reallocate KCPD funds, replace Smith and gain local control of the department.