‘When you prioritize the most vulnerable road users, you make streets safer for everyone’

Elizabeth Orosco

Northeast News

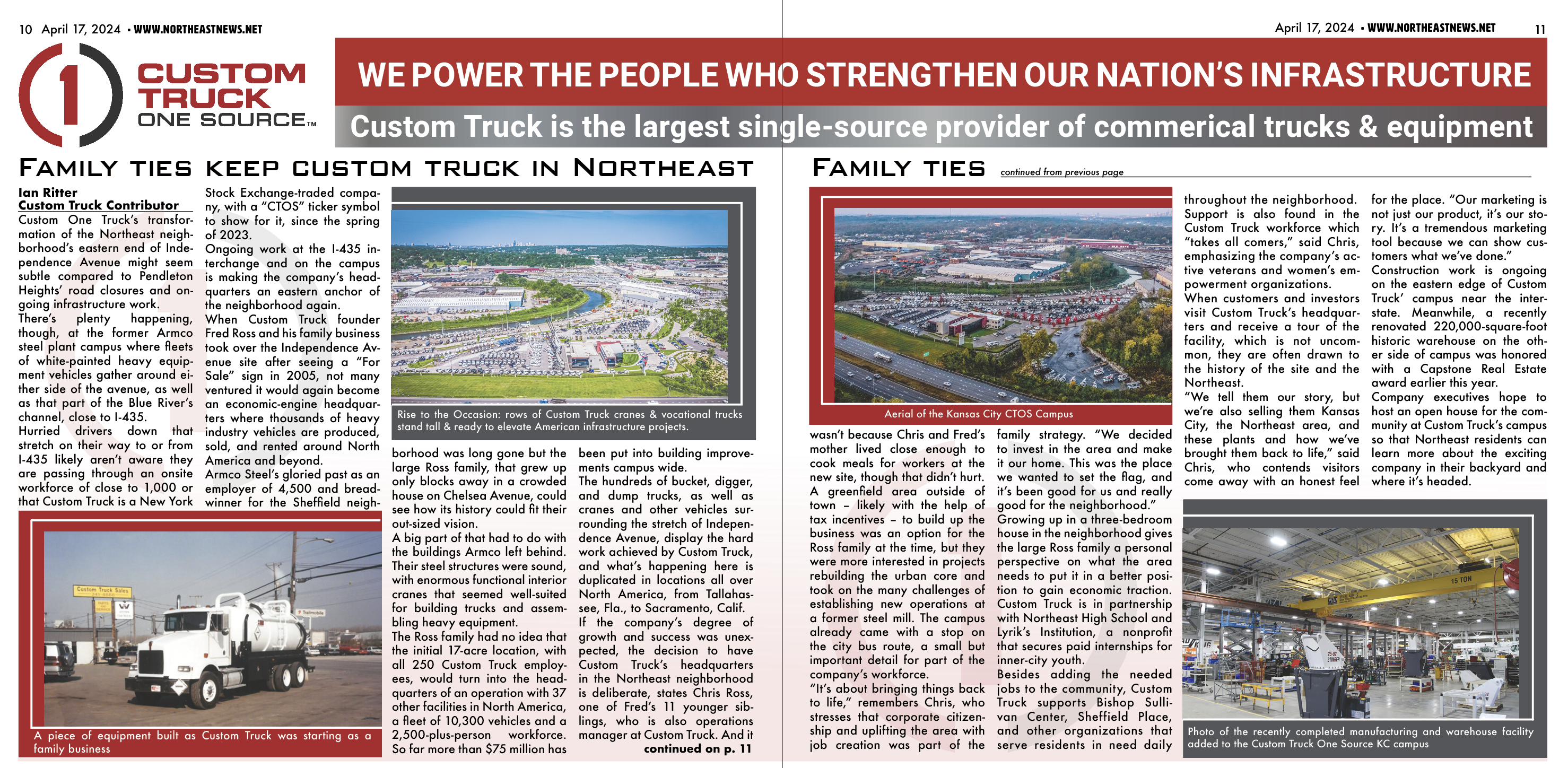

Members of the Kansas City cycling community gathered around The Scout on the first day of 2020 to remember the life of 31-year-old Pablo Sanders, a resident of KC who passed away after being hit by a vehicle on Christmas Eve while riding his bicycle.

At approximately 11:30 p.m. on December 24, Sanders was traveling westbound on Valentine Road, attempting to cross Southwest Trafficway, when he was hit by the driver of a northbound Buick.

Sanders was transported to an area hospital with life-threatening head injuries and passed away Monday, December 30th.

Kansas City Police said while the driver of the vehicle did have a green light at the time of the crash, police are investigating to determine what led to the incident.

According to KCPD preliminary analysis, there were 14 fatal crashes involving pedestrians and 2 fatal crashes involving bicyclists in 2019.

In a recent Facebook post, Mayor Quinton Lucas extended his condolences to Sanders’ friends and family.

“I’m saddened to hear of Mr. Sanders’ death. Too many cyclists and pedestrians here have died over recent years. We have to complete our unfinished work and seek new ways to protect all, not just some, traveling throughout our city. My heart goes out to Pablo’s friends and family.”

Sanders’ tragic death highlights an issue that has been discussed heavily in the bicycle community in Kansas City: just how safe are KC streets for those who choose to walk or ride a bike?

Members of BikeWalkKC, a nonprofit organization that advocates for safer streets, said something has to be done regarding the number of vulnerable road users, those who are pedestrians and cyclists, who are hurt, killed, or put in harm’s way while traveling.

The intersection where Sanders was hit is part of the Midtown Complete Streets plan, which identifies Southwest Trafficway as a major barrier to walking and biking in Midtown.

The Draft Bike Master Plan designates Valentine Road as “bike boulevard” or slow street, which would better enable cyclists and pedestrians to cross the Trafficway safely and comfortably.

However, the plan has yet to be implemented on Kansas City streets.

Liz Harris, marketing and events coordinator with BikeWalkKC, outlined several risks that vulnerable road users face at the intersection of Southwest Trafficway where Sanders was hit.

First, Southwest Trafficway is six-lanes wide, creating a large area of traffic that pedestrians and cyclists must navigate to cross.

Second, the signal does not stay green long enough to allow individuals to safely cross Southwest Trafficway.

“At that intersection, the light is very short,” said Harris. “We have seen several reports from people, who, even driving their car, struggle to get through the light while it’s still green. So you can imagine that someone walking, trying to roll their wheelchair, or biking across that intersection is really going to struggle getting across the intersection in the ‘green’ time of the light.”

Third, Harris noted that the intersection is one of the many in Kansas City that does not detect the weight of an individual on a bicycle.

“It seems that the signal is a weighted signal, so you need something far heavier than a 200-pound person and their 20-pound bike trying to trip the signal,” she said.

In Missouri, it is legal for cyclists and motorcyclists to cross through a red light in certain circumstances.

Senate Bill 368, signed in July 2009, allows motorcyclists and cyclists to safely continue through a red light if their bike has not been detected, without fear of getting a ticket.

The law provides an affirmative defense to bicyclists and motorcyclists who continue through red lights if the light does not change from red to green in a reasonable amount of time.

This bill does not allow cyclists and motorcyclists to simply run red lights. Instead, the motorcyclist or cyclist must make a complete stop and be stopped at a red light for an “unreasonable amount of time” before proceeding.

If the traffic signal is malfunctioning or if it is programmed to change only upon detecting the weight of a vehicle and the light has not changed, motorcyclists or cyclists are allowed to proceed through the red light as long as no other motor vehicle is approaching.

This, of course, poses issues of safety for cyclists who choose to continue through a red light and many are instead calling for traffic engineers to recalibrate traffic signals to detect bicycles.

“There are a few signals in town that will never pick up just a person,” said Harris. “That can be convenient because sometimes it will never turn green and you will be waiting forever, but it can also be dangerous in situations like this.”

According to the Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation, “all modern traffic signals that actuate on traffic should be capable of detecting bicycles and motorcycles.”

According to Kansas City’s Public Works traffic team, the intersection of SW Trafficway and Valentine Road is equipped with video detection. Public Works staff said they are discussing what additional safety improvements can make at the intersection in the short term with existing funding, such as evaluating the signal detectors, reviewing the signal timing, and ensuring street lighting is adequate at all points of the intersection.

In the longer term, Public Works said they are committed to building out Complete Streets around the City by integrating bike lane striping as appropriate into the Street Preservation Program (the annual resurfacing program), utilizing dedicated funding to build Complete Streets-specific projects, including multi-modal improvements with major capital projects, and piloting multi-modal facilities like on-street scooter and bike parking.

Fourth, Harris also noted that the speed limit on Southwest Trafficway is 35 miles per hour, but due to street design, drivers are often going 50 to 55 miles per hour.

“Even if you are trying to drive the speed limit, it’s difficult because of the way the road is designed and because of the way the other cars are driving on it,” she said. “It feels unsafe and unnatural to drive the actual speed limit there. That is one of the reasons that we advocate for safer road design because road design can actually make you think that you are supposed to be driving faster. Southwest Trafficway feels almost like a highway in the middle of neighborhoods where people live. Their driveways empty into Southwest Trafficway even when people are driving down it at 50 miles per hour.”

As vehicle speeds pick up, so does the risk of injury and death for pedestrians.

According to a 2011 study by Brian Tefft, a researcher at the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, the average risk of death for a pedestrian reaches 10% at an impact speed of 23 mph, 25% at 32 mph, 50% at 42 mph, 75% at 50 mph, and 90% at 58 mph.

Eric Bunch, 4th In-District Councilman and co-founder of BikeWalkKC, said his attempts to cross the exact intersection where Sanders was hit, have often been difficult.

“My experience of crossing there on a bike is that you have that double whammy of a light that doesn’t change for you and the traffic moving often at legitimately a lethal speed.”

Compared with other states and communities nationally, how do streets fare in Kansas City in terms of bicycle-friendliness?

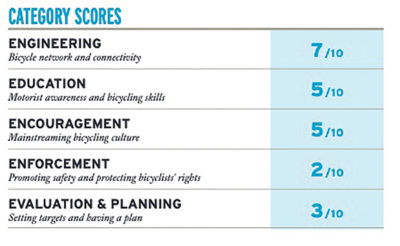

The League of American Bicyclists Bicycle Friendly America program ranks Missouri as 35th in the nation in bicycle-friendliness and rates Kansas City at a bronze level, the lowest level attainable.

These rankings are determined based on the “5 E’s for a Bicycle Friendly America,” which include Engineering, creating safe and convenient places to ride and park; Education, giving people of all ages and abilities the skills and confidence to ride; Encouragement, creating a strong bike culture that welcomes and celebrates bicycling; Enforcement, ensuring safe roads for all users; and Evaluation, planning for bicycling as a safe and viable transportation option.

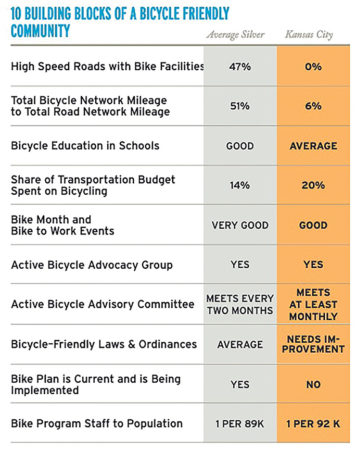

The League also lists “10 building blocks of a bicycle-friendly community,” which include high speed roads with bike facilities, total bicycle network mileage to total road network mileage, bicycle education in schools, share of transportation budget spent on bicycling, bike month and bike to work events, an active bicycle advocacy group, an active bicycle advisory committee, bicycle-friendly laws and ordinances, a bike plan that is current and being implemented, and bike program staff to population.

As vulnerable road users continue to navigate bicycle-unfriendly streets in Kansas City, many in the community are asking what can be done.

Advocating for safe streets to City Councilmembers is a way to create change, Harris said.

“What we really need to see is people who value safer streets regardless of your mode of transportation. People who value safer streets need to speak up and let their council people know it’s important to them. When you prioritize the most vulnerable road users, you make streets safer for everyone, regardless of their mode of moving through the city. If you make a road safe to cross for someone in a wheelchair, then you make it safe for a car to travel through that intersection as well because it’s going to be a more controlled intersection and it will be safer.”

Harris added that the focus should not be on the individuals themselves, but more on safe infrastructure and the built environment, which often create deadly situations.

“Instead of focusing on the people who are driving their cars or walking across the street, we need to focus on the built environment and how that can help protect people and help change our culture.”

Bunch echoed this sentiment, noting that often, victims are blamed for their injuries when they cross the street outside crosswalks or in areas that do not have a signal to cross.

“We set people up to put themselves in dangerous positions,” he said. “That is a decision that we have made as a city to not give people safe places to cross the street, so people will cross where they think it’s the safest or it’s the most convenient. Then we want to blame them for their death, but we have designed it in a way where they’re never going to be safe.”

Bunch will be introducing a Vision Zero Action Plan to City Council this week that aims to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries in Kansas City by 2030.

Vision Zero is a multi-national road safety project that aims to create a highway and road system that results in zero fatalities or serious injuries from traffic crashes and is based on a guiding principle that it is “not ethically acceptable that individuals are killed while traveling on the road transport system.”

The action plan states that serious traffic crashes are entirely preventable through better street design and will implement a data-driven approach to identify high-need areas to implement design solutions such as traffic calming elements, road diets, narrower lanes, bicycle lanes, and better pedestrian accommodations.

The resolution asks the City Manager to create and implement Vision Zero Action Plan, create a Vision Zero Task Force no later than May 1, 2020, and present the Vision Zero Action Plan to City Council no later than Sept. 1, 2020.

The action plan also includes an equity component that acknowledges the high number of pedestrian injuries on Kansas City’s east side, and asks that the plan be considered for inclusion in the five-year capital improvement plan.

Ultimately, Bunch said the mission with implementing safer streets is to save lives.

“At the end of the day, if our goal is to save human lives and we’ve accomplished that, we have done the right thing.”

Comments are closed.