Michael Bushnell

Publisher

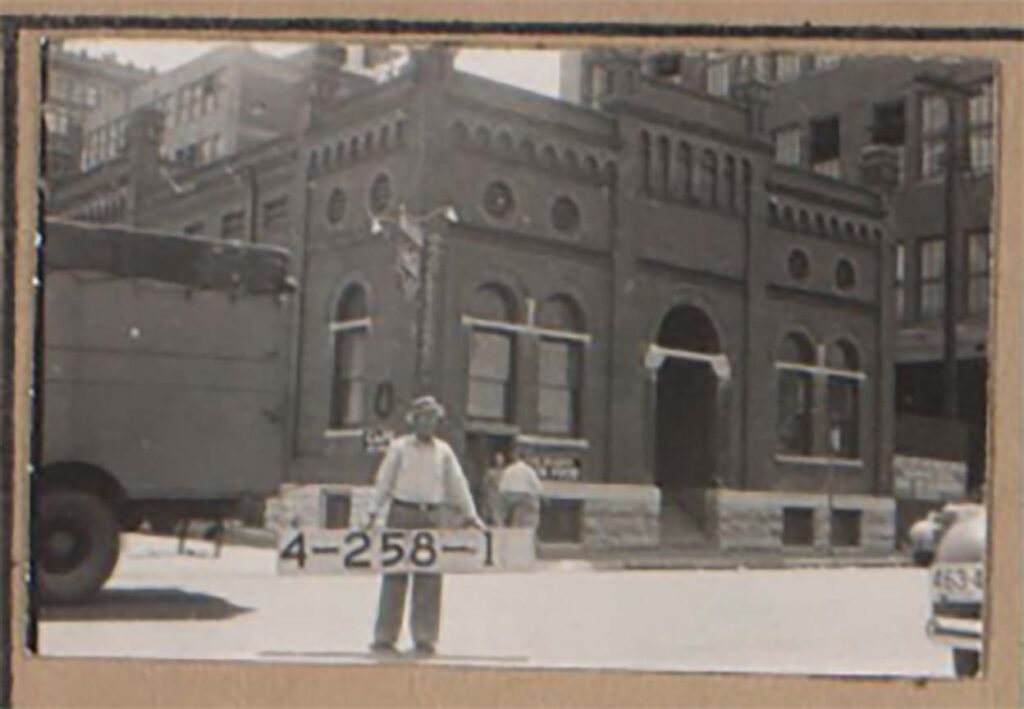

While William J. Lemp Brewing Company did not have a brewing presence in Kansas City, the Romanesque and Gothic-styled, one-story Lemp Depot at 215 E. 20th Street in the Crossroads District is the last remaining standard of the Lemp or Falstaff brands in Kansas City.

Johann Adam Lemp was one of a number of German immigrants who arrived in the United States in the 1840’s and 1850’s and began producing lager beer, having a significant impact on the beer culture in many cities, specifically in the Midwest.

Lemp is credited with introducing lager beer to Missouri in 1840 after purchasing a small grocery store in St. Louis, where he brewed small batches of Lager in the back for sale to his customers. Two years later, he founded Western Brewery and began selling his product exclusively in Lemp’s Hall, a saloon on the brewery’s premises.

By 1860, Lemp’s production had swelled to 8,300 barrels per year, eclipsing then-three-year-old Anhueser-Busch, the upstart partnership between soap-maker Eberhard Anheuser and his brother-in-law Adolphus Busch.

Brewery founder Adam Lemp died in 1862. According to the website beerhistory.com: “In his will, Adam Lemp bequeathed the Western Brewery to both his son William Jacob Lemp and grandson Charles Brauneck, along with “all of the equipment and stock. There may have been friction between the two inheritors of the brewery, as the will contained the condition that if either contested the will, the other would receive the property. Charles Brauneck and William J. Lemp formed a partnership in October 1862, and agreed to run the business under the banner of the William J. Lemp & Co. This partnership, however, was destined to be short-lived, as it was dissolved in February 1864 when William J. bought out Charles’ share for $3,000.”

Following the end of the Civil War, the brewery expanded and moved to a five-block area on Cherokee Street, above a network of caves. The location was key because, prior to the advent of artificial refrigeration, year-round brewing of lager was impossible because there was no way to keep beer at a constant 35-40 degrees. By building cellars in the caves, Lemp was able to utilize a system of flues from the above ground ice houses to keep the beer cold during the fermentation process.

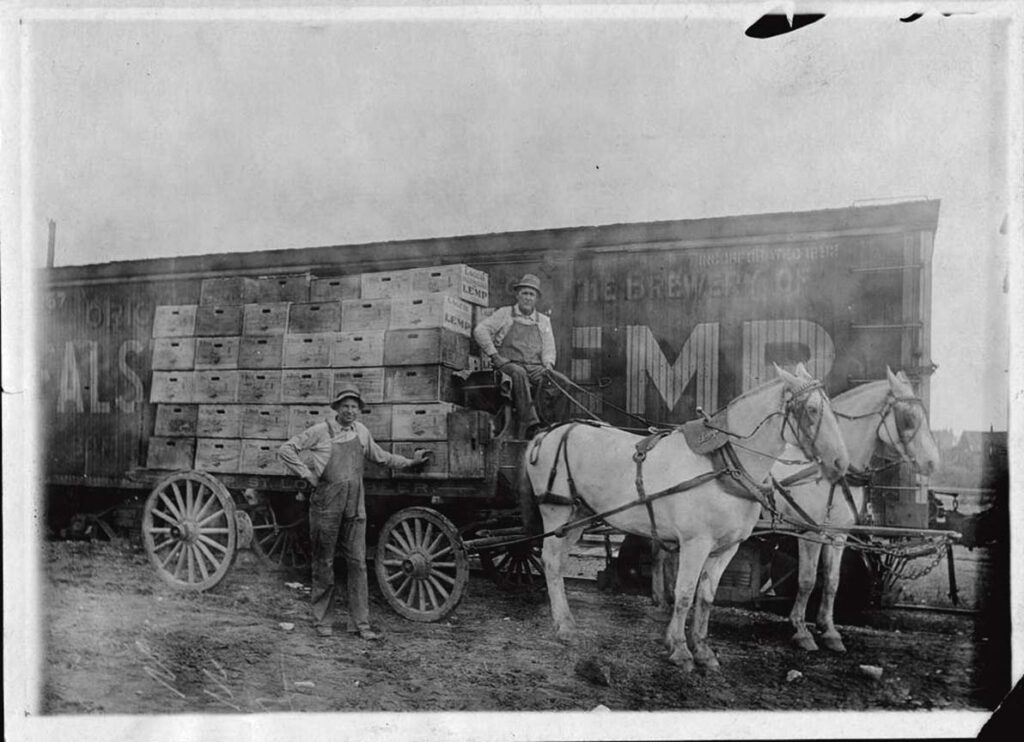

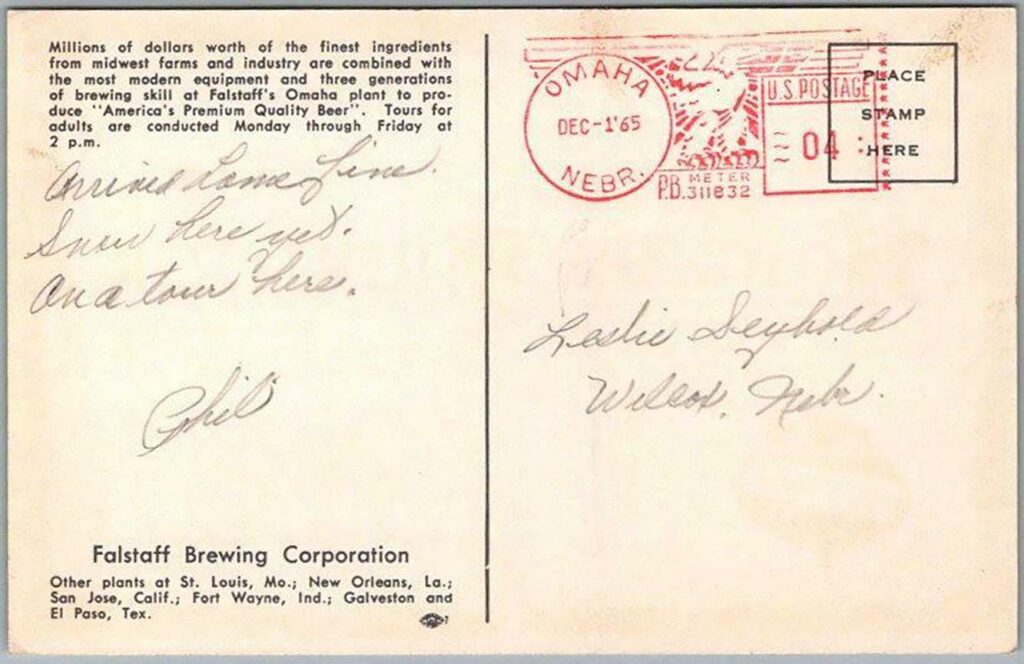

By 1895, Lemp Brewery had become the country’s eighth largest brewery, producing over 350,000 barrels per year and employing over 700 people. It was at this time Lemp released plans to construct a brick beer depot and a two-story stable at 215 E. 20th Street in Kansas City. This allowed easier access to the rail lines that brought the beer to Kansas City via rail car. The Kansas City Depot became one of over 60 depots in 29 states in which the Lemp Brewery did business. The most popular brand of beer at the time was the brewery’s Falstaff brand.

In 1901, tragedy struck the brewing family when William Lemp’s son Frederick passed away. Two years later, head of the Pabst brewing family and close friend Captain Frederick Pabst also passed away. A month later, the senior Lemp, distraught over the death of his son and closest friend, would take his own life. It would be the first of four Lemp family suicides over the next 44 years.

In 1919, following passage of the Volstead Act that ushered in Prohibition, the brewery closed. This was followed by two more Lemp suicides, Elsa Lemp-Wright in 1919 by a self-inflicted gunshot through the heart and in 1922, William Lemp Jr., following his very public divorce from Lillian Hadlan-Lemp.

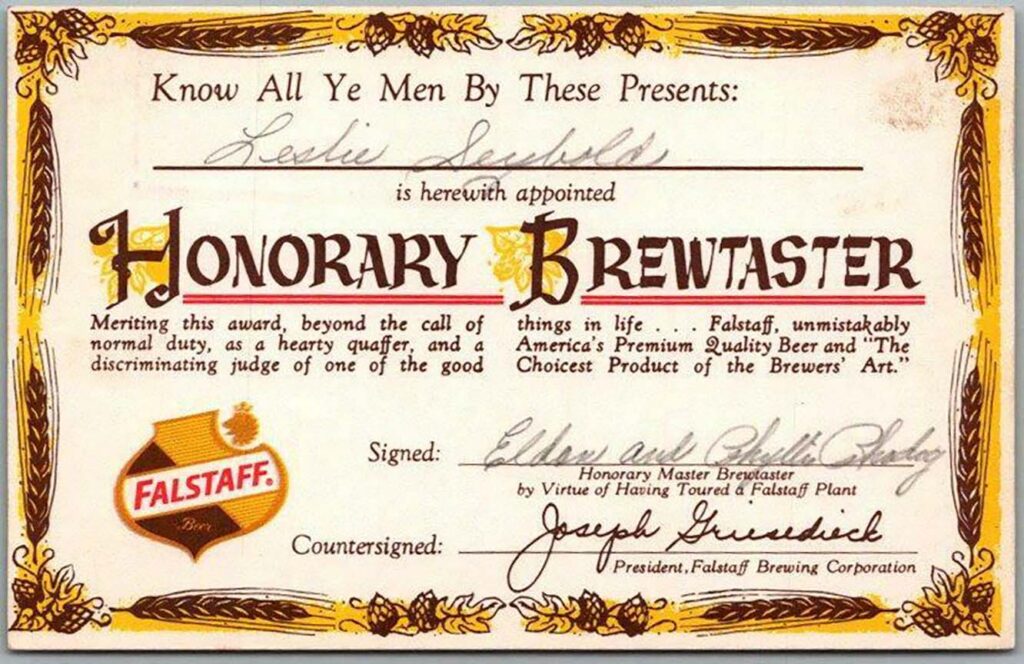

Two years after the shuttering of the brewery, the family sold the rights to the Falstaff brand, as well as the famous shield trademark, to Joseph Griesedieck , the man whose signature is on this week’s advertising postcard. Griesedieck changed the name to the Falstaff Corporation. By 1948, roughly 14 years after the repeal of Prohibition (1934), Falstaff had become the fourth largest brewer in the country. One year later in 1949, youngest son Charles Lemp took his own life.

By the early 1960’s, Falstaff had risen to become the country’s third largest brewery with plants in Omaha, Neb., El Paso, Texas, San Jose, Calif. , New Orleans, La., and Fort Wayne, Ind. The 1970’s, however, proved challenging for the company as consolidation and mergers swept the industry. By 1975, after being acquired by the S&P Company, Falstaff had slipped to 11th in sales nationally. S&P’s owner also had interests in Pabst, Pearl, Stroh’s and Olympia.

In 1985 all domestic production for Falstaff was suspended and moved to China under the Pabst brand. Fortunes continued to slide and by 2004, a little over 1,400 barrels of Falstaff were sold. Production was discontinued in 2005, ending an over 150-year brewing history.

The fate of the old Lemp Brewery depot in Kansas City has fared far better than that of the Lemp family. After landing in a tax sale on the courthouse steps in 1985, the stately old depot was slated for demolition by a real estate developer who was representing a fast-food chain.

Enter local attorney John McCay, who assembled a team of restoration and renovation types and out-bid the fast food chain and acquired the building on what equated to a promise and a handshake. Work began on the building and in 1992, McCay’s law firm, McCay, Bell and Byerly, moved into the space. That same year the firm was awarded the Cornerstone Award for completion of the project and in 1994, the Historic Kansas City Foundation presented the firm with its Preservation Award for the saving and restoration of a historically significant structure. The law firm, now McCay & Byerly, still occupies the space today.

Kansas City Public Library, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City 1940 Tax Assessment Photographs, “Hometown Beer: 1999, A history of Kansas City’s Breweries” by H. James Maxwell and Bob Sullivan Jr., www.beerhistory.com,