By Paul Thompson

Northeast News

Thu Hong Nguyen has been found guilty of six counts related to an October 12, 2015 fire she started in the northeast storage closet of LN Nails & Spa; one that ultimately claimed the lives of KCFD firefighters John Mesh and Larry Leggio.

Division 9 of the 16th Circuit Court of Jackson County was packed to the brim 20 minutes after 8 a.m. on the morning of Monday, July 23, with friends and family of the fallen firefighters waiting in anxious anticipation for Judge Joel P. Fahnestock to issue a verdict in the case The State of Missouri vs. Nguyen, who stood accused of two counts of arson, two counts of assault, two counts of murder in the second degree and one count of causing a catastrophe.

At 8:34 a.m., Fahnestock entered the courtroom and promptly delivered the verdict, beginning with a not guilty verdict on the first count of causing a catastrophe. Prosecutors would later acknowledge a brief rush of concern before the following six counts delivered the results they had fought for during the tense, week-long bench trial: guilty on each of the six remaining counts. The verdict was met with audible gasps of raw emotion throughout the courtroom.

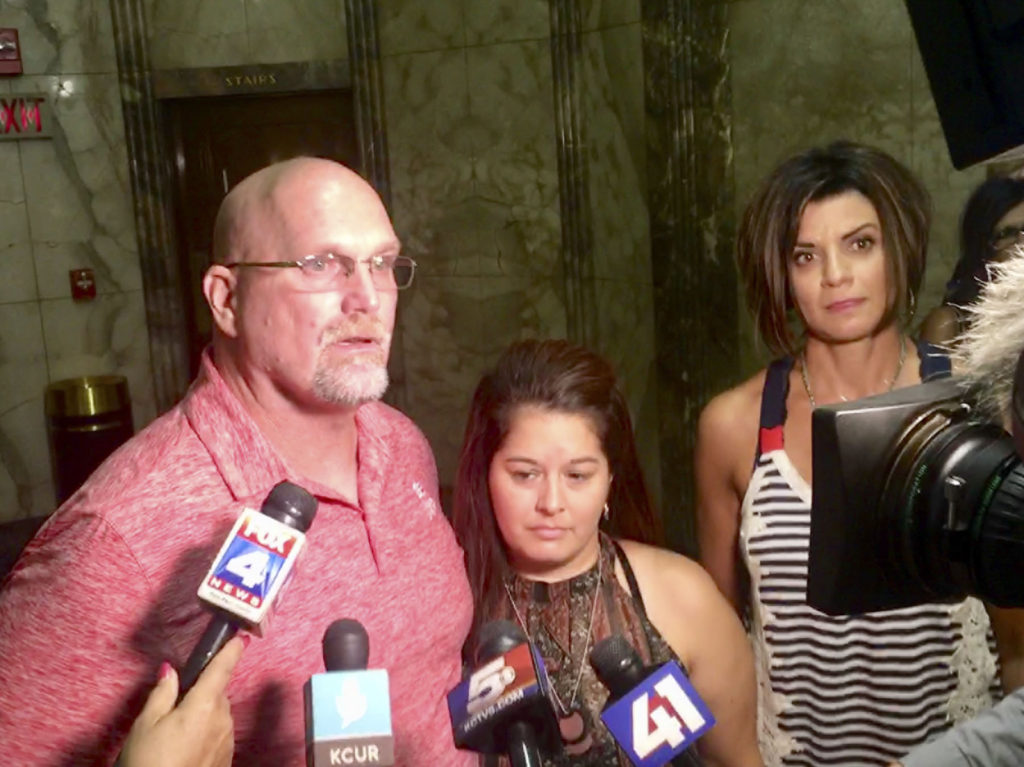

The tense moment capped an emotional two and a half year saga for the loved ones of the victims. After the verdict, Missy Leggio, widow of Larry, spoke on behalf of the Leggio family. She thanked the prosecutors, Judge Fahnestock, and the team at the department of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) for all of the hours dedicated to the case.

“It answers a lot of questions that we’ve all had deep down in our hearts, and it has lifted a little bit of weight off our chests, to where we can finally continue on with our healing process,” Leggio said.

Jim Mesh, brother of John, spoke on behalf of the Mesh family.

“I’m very happy with the verdict,” said an emotional Mesh. “It’s relief lifted off our chest, like Missy said. We’re real happy with the outcome and we’ll see what happens from here. It’s been a long couple of years.”

Nguyen was led from the courtroom in handcuffs and awaits a sentencing hearing, which has been scheduled for Friday, September 14.

The bench trial in the case of The State of Missouri vs. Nguyen began on the morning of Monday, July 16. On that day, opening statements were delivered and the first witnesses were called to the stand to provide testimony. In what was described as an emotional day in court, first-person testimony was provided from firefighters who were standing alongside Mesh and Leggio on the day of the deadly blaze.

As the rest of the bench trial proceeded throughout the week, the Northeast News was on-hand to provide daily dispatches from the courtroom. The prosecution team of Dan Nelson, Dan Portnoy and Theresa Crayon presented expert testimony from fire investigators, electrical engineers, interpreters, financial analysts and first-hand witnesses, while defense attorney Molly Hastings conducted cross examination in an effort to prove reasonable doubt in the case.

Key inflection points included an intense, comprehensive breakdown of Nguyen’s history of insurance claims, which included $267,000 in payouts over an eight-year period; all of which were the result of catastrophic events at nail salons. In another hectic moment, the last day of testimony on Friday, July 20 included a vital presentation about the nail salon’s Open sign that was frantically pieced together by the prosecution over the final lunch break of the week.

What follows is a day-by-day account of Northeast News’s trial coverage, beginning with expert testimony on Tuesday, July 17 and culminating with closing statements on the afternoon of July 20.

TUESDAY, JULY 17:

The prosecution alleges that a deadly fire was started in a nail salon supply closet by Thu Hong Nguyen just after 7 p.m. on October 12, 2015, right before she closed up shop for the night. The blaze, which began on the ground floor of a mixed-use, three-story apartment complex, claimed the lives of Kansas City firefighters John Mesh and Larry Leggio. The firefighters died when a brick wall collapsed upon them while working the scene.

Witnesses called before Judge Joel P. Fahnestock in Division 9 of the 16th Circuit Court of Jackson County included Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) fire protection engineer Adam St. John, former ATF engineer Michael Keller, ATF senior forensic auditor Nicole Nguyen-Murley and FBI special agent Ryan Williams, who specializes in cell tower analysis.

St. John testified about lab testing he conducted that involved characterizing the ignition, flame spread and heat release rate for two chemicals known to be in the nail salon at the time of the fire: isopropyl alcohol and acetone. According to St. John, the testing showed that the fire was capable of spreading rapidly and could have ignited other materials.

Defense attorney Molly Hastings, however, argued that no firefighter ever made entry into the back of the nail salon on the night of the deadly fire, though she noted that they did enter other stores, as well as the second and third floor of the building. She further argued that a video of the fire shows no discernible smoke coming from the nail salon, which throws doubt on the theory that the fire originated in the salon’s supply closet.

St. John had concluded previously, however, that the origin of the fire was obscured from the street because the neighboring business had more flammable material near the front of the store. St. John also noted that KCFD thermal cameras registered an extreme heat signature coming from the back of the nail salon.

The prosecution’s second witness, engineer Michael Keller, elaborated on how the fire might have spread throughout the building without engulfing the nail salon. According Keller’s testimony, if flammable liquid had been densely concentrated in the salon’s supply closet, the flames were most likely to build upwards towards the ceiling, rather than laterally. In Keller’s scenario, the flames would begin engulfing the building from the void space between the first and second floor.

Keller was at the scene of the fire, where his initial task was to ensure the safety of the premises and provide assistance with electrical issues. According to Keller, each individual item from the building was examined by trained ATF personnel. Ultimately, Keller ruled out the possibility of an electrical fire.

“The emphasis here is that literally thousands of items were looked at,” Keller testified.

According to Keller, smart electrical meters provided the prosecution with important details about the deadly fire. Though the exterior meters were damaged by falling bricks, they remained unharmed by the fire itself and maintained the capability to download data.

The recovery of the smart meter data allowed Keller to investigate power levels from within the building in 15-minute intervals. In practice, the data helped Keller identify the speed at which the fire enveloped the building by tracking when the interior panel boxes tripped, cutting power to various portions of the structure in the process. Between 7:00 p.m. and 7:15 p.m. on October 12, 2015, Keller said, the fire began hitting power sensors. He testified that 13 of the 16 units in the structure had working smart meters attached, and that 11 of the 13 had gone to zero power by 7:17 p.m. By 7:45 p.m. at the latest, all of the power in the building was shut down.

One of the items of concern for Keller was that the nail salon is alleged to be the origin of the fire, but its power is not one of the first to go offline. The reason, according to Keller, is that the fire first reached the ceiling of the nail salon, before spreading into the void space between floors. Keller testified that a sheet rock wall protected the panel box that was located next to the area of origin, which at least temporarily allowed power to remain on in the business that was the source of the fire.

Keller’s testimony led to the most contentious interaction of the trial’s second day, as Hastings worked to establish that the building, constructed in 1947, had a history of electrical issues. She cited one tenant who described an outlet that would spark and smoke whenever something was plugged into it.

According to Hastings, there was also photo evidence that the nail salon’s Open sign – which Nguyen acknowledged was left on permanently – remained lit until 7:25 p.m. on the night of the fire, and that it was the very last business in the building to lose power. Keller concurred that the electricity in the nail salon went out after the electricity in the apartments above, though he pushed back strongly when Hasting suggested that it would be logical for the fire to have shut off the nail salon’s power first, had the fire’s origin indeed been the supply closet. Keller noted that the sheet rock wall that separated the supply closet from the panel box is designed to be fire retardant, which could have shielded the power supply from the neighboring flames.

Hastings worked to cast doubt on Keller’s theory.

“I would suggest that there is enough fuel to blast through this sheet rock wall,” she said. “One alternative reason that the light could have stayed on longest in the building, just one possible alternative, could be that maybe the area of origin was not in that closet.”

Keller’s testimony was followed by that of ATF senior forensic auditor Nicole Nguyen-Murley, who served as an interpreter for Thu Hong Nguyen when the defendant was interviewed about the deadly fire on October 26, 2015.

On July 17, Nguyen-Murley was led through a transcript of the interview, with the prosecution highlighting the conflicting statements provided by the defendant. For instance, Nguyen initially suggested that she doesn’t know how to use credit cards and doesn’t have a bank account, only to concede later that she used to have a credit card until her ex-husband destroyed her credit score.

Nguyen also indicated during the interview that she was merely an employee and that the nail salon was owned by her boyfriend Nhat Pham. Later, she suggested that she ran the business as an owner and paid $10,000 for a stake in it.

She initially told authorities that she was a simple woman who wasn’t plugged into the financial aspect of the nail salon, and that she subsisted on $250 in food stamps, $200 in monthly childly support, and what she earned as an employee of the business. Later, she revealed that she actually took home the cash portion of the business’s sales, while Pham collected the credit card revenue. Despite her suggestion that she spoke little English, Nguyen-Murley testified on July 17 that the defendant spoke English at various points throughout the interview, including during the entire second half as Nguyen-Murley watched from a monitor.

That proved to be a point of contention for Hastings, who questioned Nguyen-Murley about why she would leave the interview. Hastings pointed to a portion of the transcript where Nguyen indicated that she needed an interpreter. Hastings cited the incident as an indication that her client was having trouble communicating.

When Nguyen asked again for a translator, the lead investigator called her out; saying that her English is strong enough to speak without an interpreter. In a strange development, Hastings also pressed Nguyen-Hurley to acknowledge that the six and a half hour interview ended with Nguyen vomiting.

Hastings asserted that the interview was aggressive, especially considering that Nguyen-Murley stated at the beginning of her testimony that the defendant was not yet a suspect at the time. Hastings pointed to an entire passage that shows Nguyen-Murley talking to the defendant in Vietnamese.

“Stop talking, cut it off, this is going to take a long time,” Nguyen-Murley said, according to the transcript. “If you want to go home with your kids, just tell me the truth.”

Nguyen replied: “I just told you the truth.”

Prosecutors, meanwhile, focused on Nguyen’s inconsistencies and suspicious behavior. For instance, she acknowledged that she bought between $400 and $500 of flammable beauty supplies on or around the same day as the fire. Nguyen also told authorities during her interview that Pham helped her close the shop on the night of the fire, though by that time investigators had determined that Pham’s phone had been pinged at Argosy Casino while Nguyen was closing up the business.

The final witness of the day, FBI agent Williams, laid out how exactly investigators were able to determine the whereabouts of both Pham and Nguyen on the evening of October 12, 2015. Williams is a member of the FBI’s Cellular Analysis Survey Team (CAST), a group of 60 agents and task force officers that specialize in deciphering cell phone records.

Williams was part of the team that monitored the cell phone records of Pham and Nguyen. According to Williams, those records show a flurry of activity between the pair from 7:40 p.m. to 8:10 p.m. – the hour following the fire – on October 12, 2015. During this time, Nguyen initially told authorities that she and Pham were together, but Williams’ testimony proved otherwise.

Nguyen’s phone did indeed ping in the area surrounding the nail salon, and later in the vicinity of her home on St. John Avenue. During that time, however, Pham’s phone registered at a Burger King in North Kansas City. His phone later pinged at Argosy Casino, and only well after 8 p.m. did the phone return to the Historic Northeast.

Pham was allegedly with another girlfriend when the fire occurred. That individual submitted testimony approved by both the prosecution and defense that corroborates the prosecution’s version of events, including time spent at Argosy Casino and the Burger King location in the Northland, where the witness acknowledged that Pham had dropped her off at her car.

She added that at one point, Pham received a telephone call, during which she claims to have heard a deep male voice say that the nail salon was on fire.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 18:

Five more witnesses were called to the stand on Wednesday, July 18 in the case against Nguyen.

The third day of Nguyen’s bench trial on charges of 2nd Degree Murder and Arson was dominated by the testimony of ATF special agent Ryan Zornes, a Certified Fire Investigator (CFI) who worked the arson case related to the deadly October 12, 2015 Independence Avenue fire.

The prosecution worked early on to characterize Zornes’s credentials as impeccable. He was required to work 100 fire scenes and complete at least 80 hours of courses in order to be certified as a CFI – a certification earned by only about 100 ATF agents. Since becoming a CFI, he has worked approximately 250 additional fire scenes. Named as the lead investigator in the deadly Independence Avenue fire, it was Zornes who ultimately declared that the fire was incendiary, or caused by a human act. It was also Zornes who initiated the criminal case against Thu Hong Nguyen.

While on the witness stand, Zornes ran through the order of steps in a fire investigation: 1) determine the location of origin; 2) determine cause of the fire; 3) determine classification: Accidental (electrical, spontaneous combustion), Natural (lightning strike), Incendiary, or Undetermined; 4) if classified Incendiary, a criminal investigation is conducted.

In describing his methodology, Zornes described his deference to the scientific method, suggesting that as a highly-trained CFI, he was keenly aware of the dangers of presumptive bias when conducting a fire investigation.

“There are just as many accidental incidents as there are incendiary incidents,” Zornes said. “Again, when we arrive we don’t know what the cause is; that’s why we’re there.”

The prosecution established the level of detail that went into the ATF investigation throughout the morning. The origin and cause investigation included more than 30 firefighter statements, more than a dozen resident statements, seven business statements, three statements from adjacent businesses, conversations with the building owner, 10 days of excavation, and extensive cognitive and laboratory testing. The investigation was described as a team effort; in total, 138 personnel assisted with the fire investigation between national and local components, all of whom were there within 24 hours of the incident.

When the work was over, Zornes concluded that the fire originated in the northeast corner of the storage closet in Thu Hong Nguyen’s nail salon (LN Nails & Spa), and that the cause was intentional.

Many of Zornes’s findings were informed by firefighters who responded to the scene. One reported seeing a white-hot heat signature in the area around the nail salon, while another reported that the flames in Apartment C of the three-story, mixed-use building – located directly above the nail salon – was the hottest he had ever felt at a scene. That firefighter further stated that he felt like he was “being baked from the floor” while in the apartment. Two more firefighters said they punched a hole in the northeast wall of the African Store, which was directly next door to the nail salon, where they observed significant fire coming from the area of origin.

Though Zornes and his team did not uncover any heat sources (lighters, matches, etc.) in the proposed area of origin, ATF guidelines allow investigators to infer that a heat source such as a lighter has been removed from the scene of an incendiary fire.

The fire investigator was also able to obtain surveillance footage that showed Nguyen and nail salon employee Long Pham leaving the business on October 12, 2015. The surveillance footage, shot from the Safari Cafe restaurant across Independence Avenue, shows one individual leave the store at 7:10 p.m., and a second individual turn off the interior lights and follow shortly thereafter at 7:12 p.m. Store employee Long Pham later testified that he was first out the door, where he waited for Thu Hong Nguyen to close up the shop. By 7:17 p.m., the building’s electricity had begun to shut down as a result of the flames reaching the structure’s electrical system.

Later in the investigation, Zornes looked at the insurance and financial pictures of the building. The owner of the three-story structure was a man named Bo Tran, but Tran could no longer insure the building after a January 2015 apartment fire. Tran’s insurance was changed after January 2015 – from a policy that paid out to him to a policy that would pay out to the mortgage company, Country Club Bank, which held the note on the building.

The prosecution argued that nail salon employee Long Pham also stood to gain nothing from the fire. In fact, Long owned the tools he used for the business, and they were destroyed in the fire. Because they were valued by Pham at more than $1,000, and he lost his place of employment, Zornes concluded that Long was actually hurt financially.

Defense Attorney Molly Hastings, meanwhile, questioned the recollection of firefighters at the scene and worked to establish that the building had been plagued with electrical issues prior to the blaze during her cross examination, which lasted almost as long as Zornes’s direct testimony.

One focus was the fact that a firefighter forced entry into the front door of the nail salon, but none of the firefighters actually entered the salon. It stands to reason, Hastings opined, that if firefighters on scene had seen fire in the salon, they would have entered.

Hastings also focused on the statements provided by tenants of the second and third-floor apartments, who lived above the first-floor retail businesses. One couple, the Bui’s, said that they saw smoke at around 7 p.m. If accurate, Hastings said, that would have been while Nguyen was still in the salon. Zornes responded, however, that the statement from the Bui’s was an approximation.

Another tenant, Ricky Davidson, told authorities that his fan started smoking on the evening of October 12, but he never said what time it started smoking at. The building’s owner, Bo Tran, told one tenant not to talk to the investigators or mention any electrical work that had been done in the building. A resident named Rodney Blasche said that the smoke smelled like burning electrical wires, while tenant Lawrence Lee said he had numerous problems throughout the apartment, and that he would often blow the breakers. At least two tenants, Hastings added, said that there was exposed wiring in their apartments.

The second witness of the day was Misty Levron, an informant who was first introduced during the testimony of Zornes.

Levron told Zornes that while incarcerated with Thu Hong Nguyen, the defendant acknowledged culpability for starting the deadly fire. According to Levron, Nguyen told her that she set a fire that killed people using liquid from her nail salon. Nguyen said that she didn’t expect things to go wrong, and that she had done it before, but that she had never been investigated for it.

Levron suggested that when she was initially told the information, she called her husband from jail and told him she had important information she needed to tell someone about.

Hastings was quick to question the story of Levron, who she said was being held on a warrant related to providing false or inaccurate information in an effort to get pills from a hospital.

While Zornes contended that Levron was never offered anything in exchange for her testimony, Hastings countered that Misty Levron made 51 phone calls before she sat down for her interview with ATF. Recorded calls from jail revealed that Levron told her husband she was only going to meet with law enforcement if her charges were dropped.

Zornes agreed that in his understanding, Levron initially intended to withhold information on Nguyen’s case unless her charges were dropped. Ultimately, though, he said that Levron provided information without help from authorities. That said, Hastings pointed out that Levron was released from prison two weeks after the interview, and was never extradited back to Florida, where her initial infraction occurred.

In her own witness testimony, Levron said that she first met Nguyen after the defendant’s more than six-hour interview with ATF officials in late October of 2015. Levron said that she felt bad for Nguyen, who seemed scared, and that the two huddled together for warmth while locked in a cold cell. After hearing what amounted to a confession from Nguyen, Levron developed a plan: to take the information she had been given to try and convince law enforcement to help her with her charges.

Levron eventually contacted a case manager in the Jackson County jail, asking about the timeline for her own case and implying that she had important information from another inmate. That didn’t pan out, so roughly two weeks later, Levron says that she reached out to a corrections officer. In the meantime, Levron had seen on TV that Nguyen had been charged with murder.

She ultimately abandoned her plan to leverage that information, she says, feeling a change of heart based on the severity of the case.

“That could have been my kids,” Levron said. “I didn’t want that blood on my hands.”

Hastings pressed Levron on that issue. During Levron’s prior deposition with Hastings, she had suggested that by the time she met with ATF officials, she would have turned down help with her outstanding warrants, even if authorities had offered it as a sort of in-kind donation. Hastings pointed out that Levron seemed to waver between extremes; in one moment hoping to leverage the damaging information about Nguyen, and in another, at least hypothetically rejecting it.

“You wanted to use the information to leverage a benefit for yourself, and you admit that was your initial plan,” Hastings said.

Eventually, the topic moved to Levron’s outstanding tickets in Jackson County. Hastings wanted to know: was Levron going to take care of that ticket right after court?

“I have the money to pay my ticket,” Levron responded.

Hastings repeated the question: you’re going to take care of that right after court?

Levron repeated her reply: “I have the money to pay my ticket.”

“I’ll take that as a no,” Hastings responded, before telling Judge Fahnestock that she had no further questions.

The last three witnesses of the day focused on Lee’s Summit, Missouri, where another of Thu Hong Nguyen’s nail salons suffered fire damage back on July 25, 2013.

The first of the three Lee’s Summit witnesses was Melissa Vaughn, who was at the salon in question on the day of the fire. Vaughn was having her tires changed at a nearby auto shop, and had enough time to get her nails done at Nails U.S.A., where Thu Hong Nguyen worked. Vaughn had never been there before, and she said it took about a half hour.

When the pedicure was finished she went outside to let her toes dry and smoke a cigarette. Eventually she saw the three employees leave the store, and realized that they were leaving early. She didn’t think much more of it, and went to a tanning salon to browse the shelves. When she left the tanning store, she walked back past the nail salon and saw amber lights inside the store. After a beat, she identified the lights as a fire and called the police. Vaughn then went to alert neighboring businesses that there was a fire in a nearby store.

The next witnesses were Lee’s Summit Police Officer Eric Hennig and Lee’s Summit Fire Department fire investigator Shawn Burgess. Hennig responded to the fire at Nails U.S.A. on July 25, 2013, while Burgess served as the fire investigator at the scene.

Hennig was working crowd control, allowing firefighters to do their job.

“Once the fire was contained, I was approached by three women,” Hennig said. “One said she worked at the business and was the mother of the owner.”

That woman said that they closed up at approximately 6:30 p.m. due to lack of business, and added that approximately 10-15 minutes after she had left, she received a phone call from her son, who said that she needed to go back because there was a fire at the building.

Burgess classified the cause of the Lee’s Summit fire as a probable accident. Since that time, though, he suggested that he has received additional training as a fire investigator. He now acknowledges that he never talked to the Lee’s Summit Police Department, the 9-1-1 caller, other employees of the nail salon or the insurance investigator before he made his determination.

Burgess added that his conclusions about the fire would be different today, thanks to the additional training and experience he has gained over the intervening years.

“I would have classified it as an undetermined fire.”

THURSDAY, JULY 19:

The prosecution worked to establish a pattern of insurance abuse during a bombshell fourth day of testimony on Thursday, July 19.

Prosecutors presented evidence aiming to prove that the Independence Avenue fire was intentionally ignited as part of an ongoing scheme that netted five businesses owned and/or operated by Nguyen $267,000 worth of insurance claims over a roughly eight-year period.

Forensic auditor Nicole Poirier testified that she was contacted by ATF special agent Ryan Zornes in October of 2015 and asked to conduct a financial analysis of Thu Hong Nguyen. Poirier said that she worked over 400 hours on the case, pulling credit reports, property records, bank records, insurance records and tax records.

In the course of her work, Poirier focused her attention on five nail salons that have been owned by Thu Hong Nguyen and her family since 2008: 1) PS Nails in Uvalde, Texas; 2) AV Nails in San Antonio, Texas; 3) Perfect Nails in Grandview, Missouri; 4) USA Nails in Lee’s Summit, Missouri; and 5) LN Nails & Spa in Kansas City, Missouri.

What Poirier uncovered through financial records, drawn primarily from 18 financial institutions and five insurance companies, was a familiar theme: each of the businesses connected to Nguyen – either in her name or that of her ex-husband, son, or boyfriend – eventually succumbed to a catastrophic event before collecting an insurance payout that exceeded the initial purchase price of the business.

The following was revealed in rapid-fire succession, during a back and forth between Poirier and Jackson County Chief Deputy Prosecutor Dan Nelson:

– PS Nails, the only nail salon that Nguyen owned in her name, was purchased for $27,000 and remained open from December 2006 until July 2008. It suffered fire damage in July 2008 and Nguyen collected a $30,286 insurance payment. The business never reopened.

– AV Nails was purchased for $38,000 in June 2009, with ex-husband Michael Nguyen and teenage son Cuong Nguyen listed as signatories. The business operated for four months. After a fire in October of 2009, the business received an insurance payout of $62,344. The nail salon never reopened.

– Perfect Nails was purchased for $15,000 in October 2010, with Cuong Nguyen listed as the signatory. After 7.5 months in business, the nail salon increased its insurance policy on June 9, 2011. On June 11 the salon was burglarized, after which a $41,855 insurance payout was collected. The business never reopened.

– Nails USA was purchased for $20,000 in January of 2012. After operating for 18 months, there was a fire. The nail salon received an insurance payout of $51,873. The business never reopened.

– Finally, LN Nails & Spa was purchased for $20,000 in July 2014. According to witness testimony, Thu Hong Nguyen split the cost of the business down the middle with her then-boyfriend, Nhat Pham. In January of 2015, a fire in an above residential apartment led to flooding in the building. Pham filed an insurance claim and received a $40,000 payout. The business nevertheless remained open until October 2015, when a deadly fire destroyed the building in which it was housed. Pham filed an insurance claim and received an initial payment of $2,000. However, he was later advised by his attorney to withdraw the claim.

Poirier testified that following a catastrophic event, companies have to provide information about how much money they would have received during the months when they were claiming lost income. According to her analysis, those figures were routinely inflated by Nguyen and her business partners.

“The defendant claims almost double what she was actually able to support,” Poirier said. “That tells me that she overinflated her receipts for the purpose of the insurance payout.”

During cross examination, defense attorney Molly Hastings called out Poirier for selective research, suggesting that Independence Avenue building owner Bo Tran had also racked up roughly $700,000 in insurance claims related to fires over a similar timespan as Nguyen.

Hastings also took issue with the insinuation that Nguyen had access to all of the $267,000 in insurance claims that have been paid out to her businesses since 2008. After all, she pointed out, nearly every nail salon Nguyen has worked at has – at least on paper – been owned by another individual. What’s more, Hastings noted, insurance companies have an opportunity to investigate any insurance claims they feel are improper.

“All of these claims that we have seen to date; none of them except for the first were written to Ms. Nguyen,” Hastings said. “They don’t see a problem, and they are issuing compensation based on what they feel the claim is worth.”

“It makes sense,” Hastings continued. “The insurance company is not going to hand out money to people who are ripping them off, right?”

The day began with less dramatics, as most of the testimony focused on the 2013 fire at the Lee’s Summit nail salon, Nails U.S.A.

The first witness called to the stand on July 19 was Kirk Hankins, a former private fire investigator. Hankins investigated the July 25, 2013 fire that occurred at the Lee’s Summit nail salon. Hankins took the stand to offer his own interpretation of the Lee’s Summit fire, which he investigated on behalf of the State Farm insurance company.

Hankins testified that he wasn’t able to determine a cause of the fire: he considered many hypotheses in his investigation, but he ruled them all out through fire pattern analysis. He recommended that his client bring in an electrical engineer to eliminate the hypothesis that electrical failure was the cause of the fire.

According to his testimony, Hankins believed that the hypotheses related to electrical failure and incendiary fire needed “further testing and validation.” He ultimately classified the Lee’s Summit fire as undetermined, noting a lack of evidence of incendiary causation. Hankins said the reasons for the classification included the fact that items weren’t removed from the store prior to the fire, and that there was no evidence of an exotic accelerant; though there were ignitable liquids in that cabinet where the fire originated.

The second witness of the morning was former ATF engineer Michael Keller, who had previously provided testimony related to his analysis about the October 12, 2015 fire. Keller also got involved in the analysis of the Lee’s Summit fire, at the behest of special agent Ryan Zornes.

Keller conducted a simulation: he bought roughly a dozen power strips of the same make and model as the power strip found in the area of origin for the July 25, 2013 Lee’s Summit fire. While analyzing pictures of the power strip found in that blaze, Keller was surprised at its condition.

“It struck me during the analysis…we might have expected to see more damage,” Keller said.

Keller recalled that the researchers had access to one cabinet from the scene that was replicated for the laboratory fire testing. They conducted multiple versions of what were referred to as failure tests: some were conducted with the cabinet opened, some with it closed, and some with various materials inside the cabinet.

Keller was able to develop an expert opinion based on the testing, testifying that he did not believe that the power strip was the failure mechanism that caused the fire.

During cross examination, Hastings pointed out that Keller never conducted any fire tests with flammable materials in the cabinet. She also recalled prior testimony which suggested there were at least three items plugged into the power strip at the time of the fire, suggesting that Keller’s simulations did not appropriately mimic the Lee’s Summit fire. Keller responded that the items plugged into the power strip during the Lee’s Summit fire didn’t have an effect on the power strip because they likely weren’t turned on, which would mean that there was no current going into the strip.

“In order for something to have a failure, there has to be some sort of current flowing through it,” Keller said.

Next up was Trevor Maynard, a fire research engineer who has been working at the ATF since April 2015. Currently, Maynard is the Engineering Section Chief of the ATF Fire Research Lab.

Maynard conducted laboratory testing with the hope of determining the cause of the 2013 Lee’s Summit fire. That testing included: 1) identifying appropriate materials for desks, 2) observing effects of simulated power strip failure/evaluating variables (door position, contents), and 3) evaluating the time required for fire to grow to a size similar to that described by witnesses.

At one point, the prosecution showed a photograph of a roll of paper towels physically touching the power strip used for the simulation. Maynard explained why that test was conducted.

“As soon as you start heating a thermally thin material, very quickly the entire material heats up,” Maynard said.

So what happened? According to Maynard, in all of the tests there was discoloration, but they did not observe a sustained ignition, even when a single piece of paper towel was draped over the power strip.

“A very thin piece of paper towel is among the easiest items to ignite,” Maynard noted.

Some of the fire tests included acetone, at the request of special agent Zornes, though those tests did not include a power strip. In one example, crumpled paper towels, foam nail supples in a plastic tray, one 1/3 full acetone bottle and one 1/3 full isopropyl bottle were burned with the cabinet roughly three inches open. In that test, full fire involvement occurred after 9 minutes and 57 seconds; cabinet damage similar to scene observations occurred after roughly 15 minutes.

That said, Maynard conceded that a test conducted with the same materials – but with a half-open cabinet door – failed to induce cabinet damage similar to scene observations.

Hastings seized upon the fact that all of the burn tests conducted with acetone in the cabinet were done without a power strip present.

“This is only attempted when you’re lighting it with a barbecue lighter, never with a power strip,” Hastings said.

The defense attorney also argued about a separate inconsistency: that the power strip was plugged into another power strip during the salon fire, while it was plugged into nothing in the subsequent experiment. Along those lines, Hastings reminded Maynard that at least three items were plugged into the power strip at the time of the Lee’s Summit nail salon fire. If that was the case, why didn’t Maynard plug anything into the power strip while conducting his follow-up experiments?

Maynard responded by reiterating the point made by Keller: that items plugged into the power strip would have no effect on the ignition sequence, and thus weren’t necessary for the sake of his experiments.

After a break for lunch, Zornes was brought back to testify about his investigation into the Lee’s Summit blaze.

Zornes testified that three investigations were conducted, and three different conclusions were reached: Lee’s Summit fire investigator Shawn Burgess ruled the fire accidental; State Farm’s private investigator Kirk Hankins ruled the fire undetermined; and his own ATF investigation from December 2015 concluded that the fire was incendiary in nature.

To reach the conclusion that the Lee’s Summit fire was incendiary, Zornes ran through six hypotheses: 1) Failure of power strip light circuit, resulting in ignition of lightweight combustibles; 2) Failure of power strip through leakage current; 3) Failure of other electrical appliances (This one was eliminated before lab testing); 4) Ignition of ignitable liquid (acetone); 5) Ignition of lightweight combustibles; and 6) Intentional ignition of nail bath.

While Zornes was able to disprove the potential accidental causes through lab testing, he testified that his team was unable to disprove all three ignition scenarios. Thus, they classified the fire as incendiary.

FRIDAY, JULY 20:

The testimony has been presented, closing arguments have been delivered and a verdict in the bench trial of Nguyen is set to be delivered at 8:30 a.m. on the morning of Monday, July 23.

After a week of testimony, the prosecution’s closing argument was delivered by assistant prosecuting attorney Dan Portnoy. Portnoy began by reiterating the prosecution’s timeline, which starts with Thu Hong Nguyen lighting a fire in the northeast storage closet and leaving LN Nails & Spa at 7:12 p.m. on October 12, 2015. Five minutes later, at 7:17 p.m., the flames cut power to the 16 apartments on the second and third floors of the building. By 7:25 p.m., the Open sign at the front of LN Nails & Spa went out, and by 7:26 p.m. smoke became visible, prompting the first 9-1-1 call. The Kansas City Fire Department (KCFD) responded to the scene by 7:29 p.m. At 8:06 p.m., the east wall of the three-story building at 2608 Independence Avenue collapses, burying the four firefighters in rubble.

“This goes from being a relatively minor arson for profit to a murder,” said Portnoy. “For firefighters Leggio and Mesh, this was their last call.”

Portnoy argued that the fire was too intense by the time the fire department arrived for it to be accidental. Without an accelerant, he added, the fire would not have grown out of control with such haste. Portnoy recalled testimony from firefighters that suggested they were shocked when they arrived at the scene to see how well-developed the fire already was. One firefighter told prosecutors that it was the hottest fire he’d ever felt in 25 years of duty, and that he felt as if he was being baked from below while standing in the apartment located directly above the nail salon. Portnoy described how the heat was so immense, the floor was burning their knees and their testicles through their turnout gear.

Portnoy then turned his attention to a key argument from the defense, which goes something like this: if the nail salon had indeed been the area of origin for the deadly fire, then why did the Open sign at the front of the business shut off at 7:25 p.m., while smart electricity meters show that the power to the second and third floor apartments had shut off by 7:17 p.m.?

Initially, the prosecution had argued that a sheet rock wall that protected the panel box along the north wall of the nail salon served as a temporary shield from the flames. But that argument evolved during rebuttal on Friday, July 20, after defense witness Scott S. Cramer, a forensic engineer, delivered an opinion that the wiring which fed the Open sign would likely have connected to the panel box through wiring strung from the ceiling. If that was the case, Cramer suggested, then the Open sign wiring would surely have shut down along with the wiring connected to the second and third-floor power supply. The implication from Cramer’s testimony, if accurate, was that a flaw existed in the prosecution’s area of origin; a potential bombshell on the final day of testimony.

Hastings also questioned the area of origin identified by special agent Zornes – the basis of the prosecution’s case – on the morning of July 20.

“If Mr. Zornes’s place of origin is correct, then the fire went through the ceiling, causing the power to be cut to the apartments but dodging the panel box that serves the nail salon,” Hastings said to Cramer, who was testifying under oath.

“I don’t really understand how you can have a fire that’s in this room…how it wouldn’t have effected the circuit for the lighted sign,” Cramer replied.

A forensic engineer was now on the record providing testimony which undercut that of the prosecution’s own expert witness, former ATF engineer Michael Keller. So the prosecution brought Keller back to the stand for a rebuttal, where he was presented with a pre-fire close-up photograph of the Open sign, along with post-fire images of ground-level electrical outlets that powered the salon chairs.

“We identified receptacles in the west wall close to floor level that powered the salon seats,” Keller said.

Back to Portnoy’s closing argument: the west wall receptacle (or outlet), in Portnoy’s eyes, represented a potential alternate explanation for how the Open sign could remain on until 7:25 p.m. What if it wasn’t connected through the ceiling, but rather plugged into an outlet?

“The defendant turned off the lighting circuits before she walked out of the door. That Open sign is plugged into an outlet,” Portnoy said. “If that Open sign was plugged into a lighting circuit, it would have gone off when the defendant flipped off the lights. It didn’t.”

The arson for profit claim is also at the center of the prosecution’s case, because it establishes a financial motive for Nguyen to have intentionally lit the fire. Though Nguyen wasn’t the signatory on the vast majority of her previous nail salons – which, according to previous testimony, all succumbed to catastrophic events – the prosecution argued that she benefitted from the $267,000 in insurance payouts nevertheless. After all, Portnoy argued, it didn’t make sense that Nguyen wouldn’t benefit, especially when the signatory was her teenage son, as was the case in at least one of the catastrophic events.

“The financial motive for these fires is clear,” Portnoy argued. “She survives in part from insurance proceeds.”

In the case of LN Nails & Spa, Portnoy argued that the allure of another insurance payout was the motive.

“There’s a $40,000 insurance policy, and this is the result,” he said.

Hastings presented the closing argument on behalf of the defense, maintaining that there remains reasonable doubt as to the origin of the deadly fire. If the fire originated in the nail salon, she argued, why did none of the more than 100 fire personnel at the scene see the flames through the glass windows that fronted the business?

“In simplicity, there is truth,” Hastings said. “If the origin is wrong, the causation is wrong. If the causation is wrong, they cannot prove a crime.”

She added that firefighters went into businesses located on either side of the nail salon, while also entering the above apartments. Not one firefighter, she argued, actually entered the nail salon during the blaze.

“If they didn’t go in there, it’s because they didn’t see the fire,” Hastings said.

“What is more likely and what is more logical? That every person on scene just missed it? Or that maybe Ryan Zornes is wrong,” Hastings added. “I know no one will ever say it, but I’m going to say it; maybe he was wrong.”

Hastings also questioned the reliability of Misty Levron, who testified that Nguyen admitted to the crime while the pair were locked together in a Kansas City jail cell. She referred to Levron as a wannabe detective whose involvement in this case is as an opportunist. Hastings harkened back to the final moments of Levron’s testimony, when she failed to recall when she had even arrived in Kansas City to testify.

“She doesn’t even know when she got to town,” Hastings said.

As for the defendant’s financial incentive, Hastings correctly noted that Nguyen only personally received one insurance payment, back when her first nail salon caught fire in July of 2008. Hastings also argued that the profits from the insurance payouts were inflated by the prosecution because they were not offset by the purchase prices of the businesses.

In closing, Hastings intimated that Nguyen is something of a scapegoat; an easy target that a highly motivated group of investigators latched onto in a noble but misguided attempt to secure justice for the families of the firefighters lost on October 12, 2015.

“What we have is a highly motivated group of people who want her convicted,” Hastings said. “You can feel it. You can feel it. They want to hold her responsible for the death and injuries of these men, but they do not have it.”

In her final rebuttal, assistant prosecuting attorney Theresa Crayon raised her voice as she defended the countless hours devoted to the investigation of the deadly Independence Avenue fire.

“There is nothing, Judge, not one single thing, about this case that has been thrown together,” Crayon said. “The fact that there’s a lot of people working on this should give you confidence that this is right.”

While the closing arguments highlighted the day’s proceedings, there was also testimony provided on the morning of Friday, July 20. Before the State of Missouri rested its case, prosecutors read testimony from Hung Nguyen, the defendant’s brother.

Hung Nguyen told the prosecution that he saw smoke in the building that housed his sister’s nail salon, LN Nails & Spa, on the evening of October 12, 2015. He estimated that less than 10 minutes after he witnessed the smoke rising from the back of the building, the fire department arrived to combat the flames.

In addition, Hung Nguyen told prosecutors about a conversation he’d had with his sister a few years prior to the fire at LN Nails & Spa. The defendant had asked her brother to put a nail salon in his name, but he declined because his sister indicated that the maneuver would provide him no financial benefit.

The testimony stands out when compared to financial testimony provided the day prior which suggested that Thu Hong Nguyen had established a pattern of opening nail salons in other people’s names. Inevitably, the fates of those nail salons were catastrophic events that led to permanent closure, followed by an insurance payout that exceeded the original purchase price of the business.

The defense also brought in the aforementioned Cramer (the forensic engineer) and private fire investigator Kent Harris for testimony. Neither witness actually went to the scene of the fire, but Harris did have access to the origin and cause report authored by special agent Ryan Zornes.

With Harris, Hastings ran through an alternate timeline of events derived from statements included within the origin and cause report:

7 p.m. – Apartment residents, the Bui’s, made approximate estimate of fire first being reported

About 7 p.m. – Apartment resident Blasche reports that power is lost. Hears screaming, goes out into the hallway, and is immediately overcome with smoke.

7:10: Nail salon employee Long Pham left the nail salon

7:12: Nguyen turned out the lights and departed with Mr. Pham

7:17: (prosecution expert witness) Mr. Keller suggests that the building was starting to fail

7:25 – Signage for the salon went out.

7:29 – Firefighter Steven Davis says there is no smoke or fire coming from the south side of the business

7:30 – KCFD’s Chief Gary Wait “..asked what the fire conditions were and Pumper 10 indicated they could not find any fire…”

7:44 – Medic 9 arrived on scene (Avi Elpern): “Elpern did recall intact glass on the first floor business fronts and specifically the nail salon windows.”

8:05 – Medic 40 – Donald Phillips – arrived. “…He could see flames on the ceiling of the first floor of the building.”

Harris seized on the quote from Medic 9, Avi Elpern, that the glass in front of the nail salon remained intact at 7:44 p.m. on the night of the fire. Harris argued that if the glass hadn’t bulged or blown out by that point, then there was nothing significant going on in the salon.

“Heat is going to build on the inside there,” Harris said. “As the heat builds, it builds pressure and starts to bulge the glass.”

During cross examination, however, Portnoy questioned Harris about his credentials and his findings, which the prosecution argued were largely unsupported by evidence. In particular, Portnoy called out Harris for his unsubstantiated alternate hypotheses for how the fire could have originated.

In Harris’s six-page report, Portnoy noted, the private investigator listed four hypotheses without any evidence to back them up: 1) that the fire could have been initiated by electrical failure; 2) that the fire could have been initiated by spontaneous combustion; 3) that the fire could have been initiated by vagrants; and 4) that the fire could have been the result of electrical tools being left in the “on” position and overheating.

During his closing arguments, Portnoy succinctly relayed his impression of the two witnesses put forward by the defense.

“Their experts, your honor, are simply not credible,” he said.

This week’s edition of Northeast News is a special 20-page commemorative edition chronicling the trial of Thu Hong Nguyen. On the streets now!