Michael Bushnell

Publisher

Every spring between the years 1841 to 1857, immigrants gathered in towns along Missouri’s western border to begin their long westward journey toward Oregon Territory.

The road was long, arduous, and many did not survive the journey that often, if not started early enough, lasted into mid-October. The area that became Marysville, Kan., just north of the old Alcove Spring, was a major stop along the trail near the banks of the Blue River.

In 1849, Francis J. “Frank” Marshall, a hotel owner and pro-slavery advocate from Weston, Mo., came to the Alcove Spring area and opened a trading post and ferry operation on the Big Blue River at the Independence Road crossing of the California Road.

It was dubbed Marshall’s Ferry until 1849 when Marshall received a commission to open a post office. It needed a name, however, so Marshall chose his wife’s name, Mary and the town of Marysville was born. In 1852, Marshall was granted a commission by the Army to ferry troops and government freight across the river and was also granted a license to trade with the Pawnee tribe.

During most of the year, The Big Blue was easily forded by wagons and livestock, but for a roughly six-week period in late April and early May, it could not be crossed without a ferry. Marshall, who still spent the winter months in Weston with his wife Mary, knew this and traveled west in the early months of Spring to reopen his trading post and ferry operation, ready for the California and Oregon Trail travelers who would soon be crowding the banks of the Blue awaiting the ferry.

In 1852, Marshall’s rate for each wagon to cross the Blue was $3, charging an extra 25 cents for each additional person or animal. By 1853, Marshall’s rate was $5 per wagon and there was often a good long wait to boot, given the number of wagon trains that were headed west during the spring.

Taken from a traveler’s diary in 1853, the scene along the Big Blue at Marshall’s Independence Road Ferry crossing is described as such:

“Mid-May, 1853 River bank full and ‘roaring like a mill-race.’ There were ‘hundreds of wagons’ at camps in the vicinity. The Independence Road Crossing ferry… was a rough flat boat just large enough for one wagon and a yoke of oxen. A stout rope spanned the river, and upon it, a block and tackle run the current, propelling the boat across. The ferry men crossed a wagon every 15 or 20 minutes at $5 a wagon… The approach to the ferry was in deep mud, and had to be constantly renewed by putting down logs and boughs. One man in the ferry crew had been drowned that day and been carried downstream.”

Marshall prospered greatly from the trail trade and ran for governor of the Kansas Territory in 1855 on the pro-slavery ticket as part of what is known as the “bogus legislature.” Marshall lost the election and in 1859, despite having just completed an elegant residence in Marysville, departed Kansas for the gold fields in Colorado.

Shortly thereafter, Marysville would become the first stop on the new overland mail route, founded by Alexander Majors, William Waddell and William Russell, named the Pony Express. Though it only operated for 18 months, the Pony Express still holds a huge appeal today.

A stone barn in what is now downtown Marysville, built in 1859 by Joseph Cottrell, was leased to the Pony Express in 1860 and still stands today, housing a museum dedicated to the westward expansion and the Pony Express.

In addition to being located on the Oregon Trail and the route of the Pony Express, Marysville is located on the Mormon Trail, the St. Joe Road, the Overland Stage and The Military Road. It also holds significance as part of the Otoe-Missouria Trail.

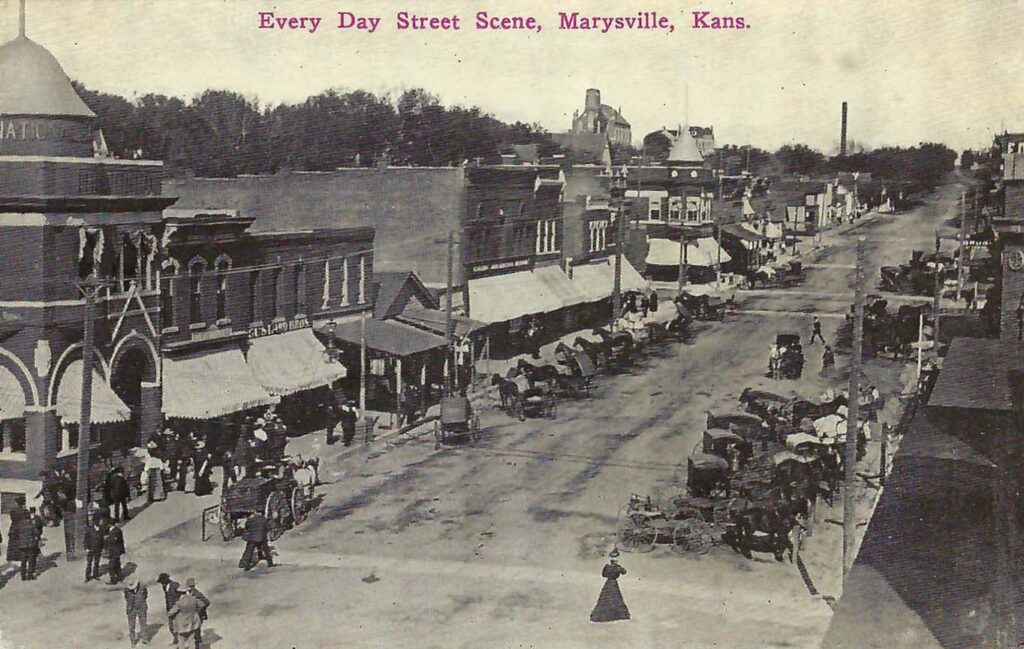

This black and white postcard was published in 1908 by F.A. Arand of Marysville and shows an “every-day street scene” in downtown Marysville.