By Michael Bushnell

Northeast News

Kansas City is known far and wide as a “river town.” Being a river town means Kansas City has had to weather floods from time to time throughout its 157-year history. Some of those events, specifically the floods of 1844, 1903, and 1951 respectively, rank as some of the greatest flood disasters in the United States. In terms of water level and cubic displacement, those three floods also rank as the most severe in Kansas City’s history.

Brush Creek, however, has flowed quietly through the valley developed in the early 1920s by Jesse Clyde (J.C.) Nichols. Soon after the development of the Country Club Plaza as Kansas City’s premier shopping destination, tiny Brush Creek was “tamed” and re-channeled amid much controversy into a concrete trough poured by then-political boss Tom Pendergast’s Ready-Mix Concrete Company. The creek flowed peacefully through the heart of the upscale shopping district, only occasionally rearing its head into what locals called a “minor threat.”

“It’ll never happen,” was oft the statement uttered by Plaza merchants and regulars alike when referring to the possibility of problems. It was just a tiny creek in a trough where people waded on a regular basis.

That would all change on September 12 and 13, 1977.

On the night of September 12, 1977, following two days of heavy rain that had saturated the ground, a wall of water raced eastward along the creek’s channel and bore down on Country Club Plaza businesses and scores of unsuspecting patrons.

On the night of September 12, 1977, following two days of heavy rain that had saturated the ground, a wall of water raced eastward along the creek’s channel and bore down on Country Club Plaza businesses and scores of unsuspecting patrons.

In a period of minutes, dozens of parked cars were swept away, block after block of shops were ravaged by the flood waters, and millions of dollars of inventory was either immediately destroyed or washed away.

In one Plaza restaurant just off Ward Parkway, flood waters surged to over five feet deep in a little over a quarter of an hour. Employees and customers fled, often with nothing more than the clothes they were wearing and what they had in their pockets.

Where there is water, there’s fire

Witnesses reported a “15- to 20-foot high wall of water” raging along the creek-bed, coming down from State Line toward the swank shopping district at close to 20 miles per hour. The low-lying bridges that spanned the creek at Wornall Road and Ward Parkway and Madison only compounded the flooding by catching all manner of debris in the narrow channel underneath, backing up floodwaters to higher levels than ever before.

Logs, debris – even cars – washed from the Plaza-area streets blocked the flood water’s passage under the bridges, creating great snags that tested the bridges superstructure. Floating debris knocked loose natural gas meters and lines from buildings, causing numerous natural gas leaks, some of which sparked explosions that created blazing fireballs throughout the night.

When the water receded less than 24 hours later, damage assessments began to run into the millions of dollars. The raging torrent had left over 1,000 people homeless, and scores more were missing. Electricity service was knocked out for over 25,000 customers, and over 15,000 homes and businesses lost telephone service for at least two days.

When the water receded less than 24 hours later, damage assessments began to run into the millions of dollars. The raging torrent had left over 1,000 people homeless, and scores more were missing. Electricity service was knocked out for over 25,000 customers, and over 15,000 homes and businesses lost telephone service for at least two days.

The grim final tally included 25 dead and over $100 million in damages.

Moving on quickly

Fewer than two days after the flood, a massive clean-up campaign was initiated by the merchants on the Plaza, as well as Kansas City at large. The merchants’ goal: be ready for the annual Plaza Art Fair scheduled a scant 10 days later.

The effort was gallant and paid off in spades. Only nine or 10 businesses wiped out by the flood opted to not re-open. Those businesses that could reopen immediately did so. The 1977 Plaza Art fair was a huge success, according to organizers. That year, on Thanksgiving Day, the Plaza lights were turned on, right on schedule with nary a sign that fewer than 60 days prior, the area had been mired in mud and wreckage. That year, more than 100,000 people attended the lighting ceremony and saw the use of 152,000 new, brighter bulbs that were installed to celebrate the success of the district following one of the worst disasters in its roughly 50-year history.

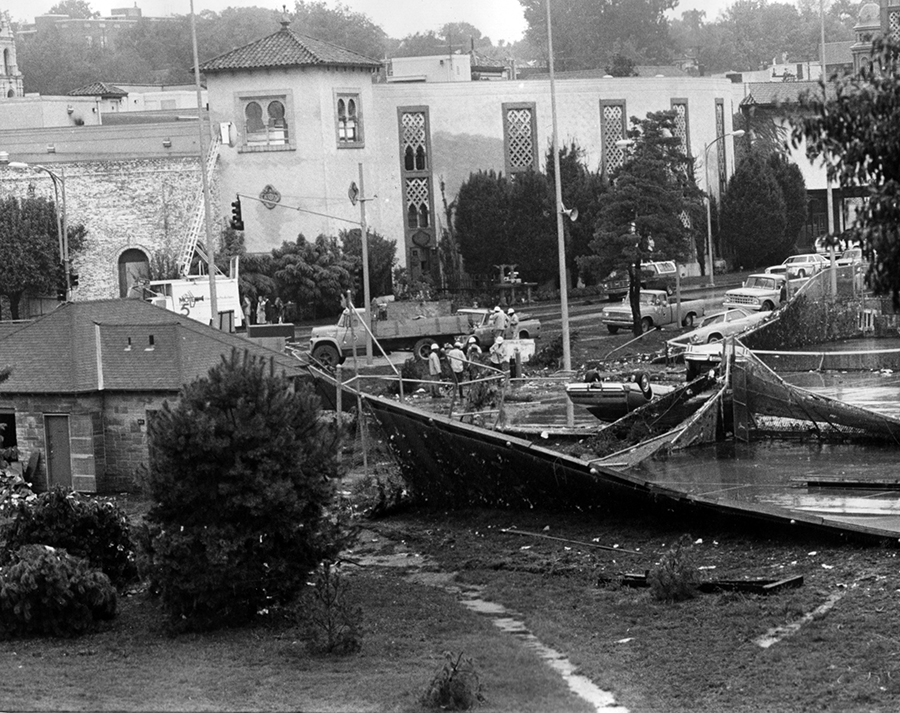

The pictures that follow on these pages of The Northeast News were pictures taken by former staff photographers following the flood. They were discovered at the office in an unmarked box tucked away in an old mahogany desk with hundreds of other pictures taken through the years.

On this 40th anniversary of the Plaza Flood, we display these pictures to memorialize those people who lost their lives in the flood and also to celebrate the Kansas City spirit that led to one of the greatest recoveries in the city’s long and storied history.