Michael Bushnell

Northeast News

During the early days of the 20th century, Kansas City’s Black population enjoyed only limited access to the tennis courts on The Paseo and in Swope Park where specific days were allotted for “colored” people to attend.

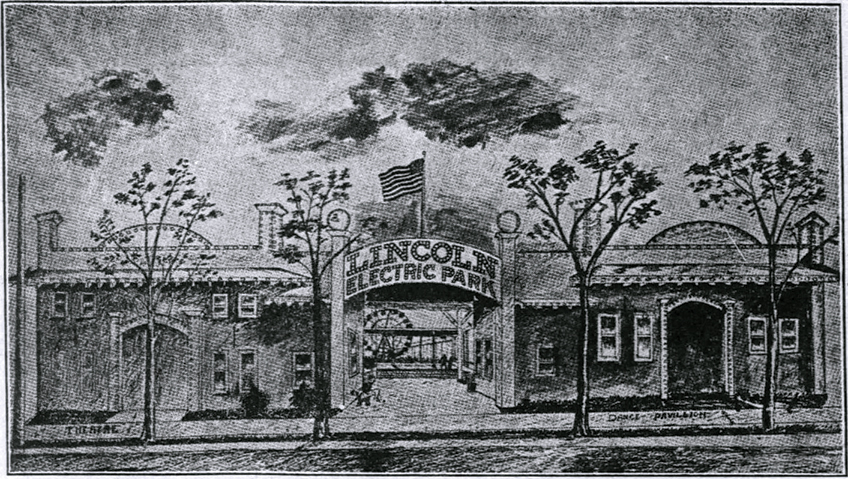

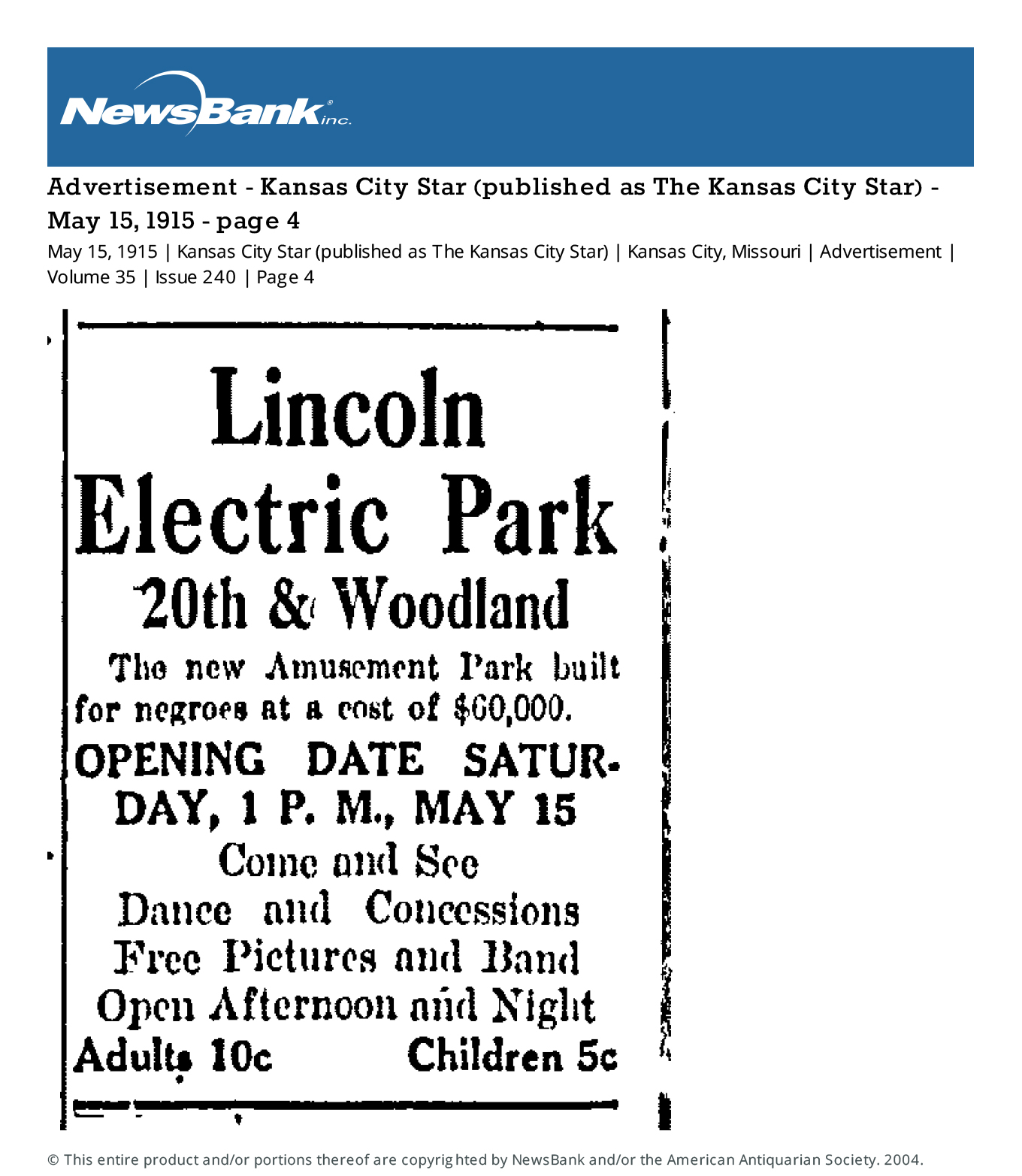

That changed in April of 1915 when a group of publicly-spirited financiers filed paperwork with the circuit court in Jackson County to establish an amusement park near 20th & Woodland Avenue for the enjoyment and patronage of the city’s Black community. Lincoln Electric Park was financed by local concrete contractor George Siedhoff, president, Locis Hector, vice president and Earl S. Ridge, secretary.

Financed for $60,000, the park stretched from Mayfield Avenue south to the Belt Line railroad between Woodland and Euclid Avenues. It opened to much fanfare in the local Black-owned press outlets on Saturday, May 15th, 1915, and boasted that it was the only park in the city being under “Negro management.” Its corporate motto: “Order at all times.”

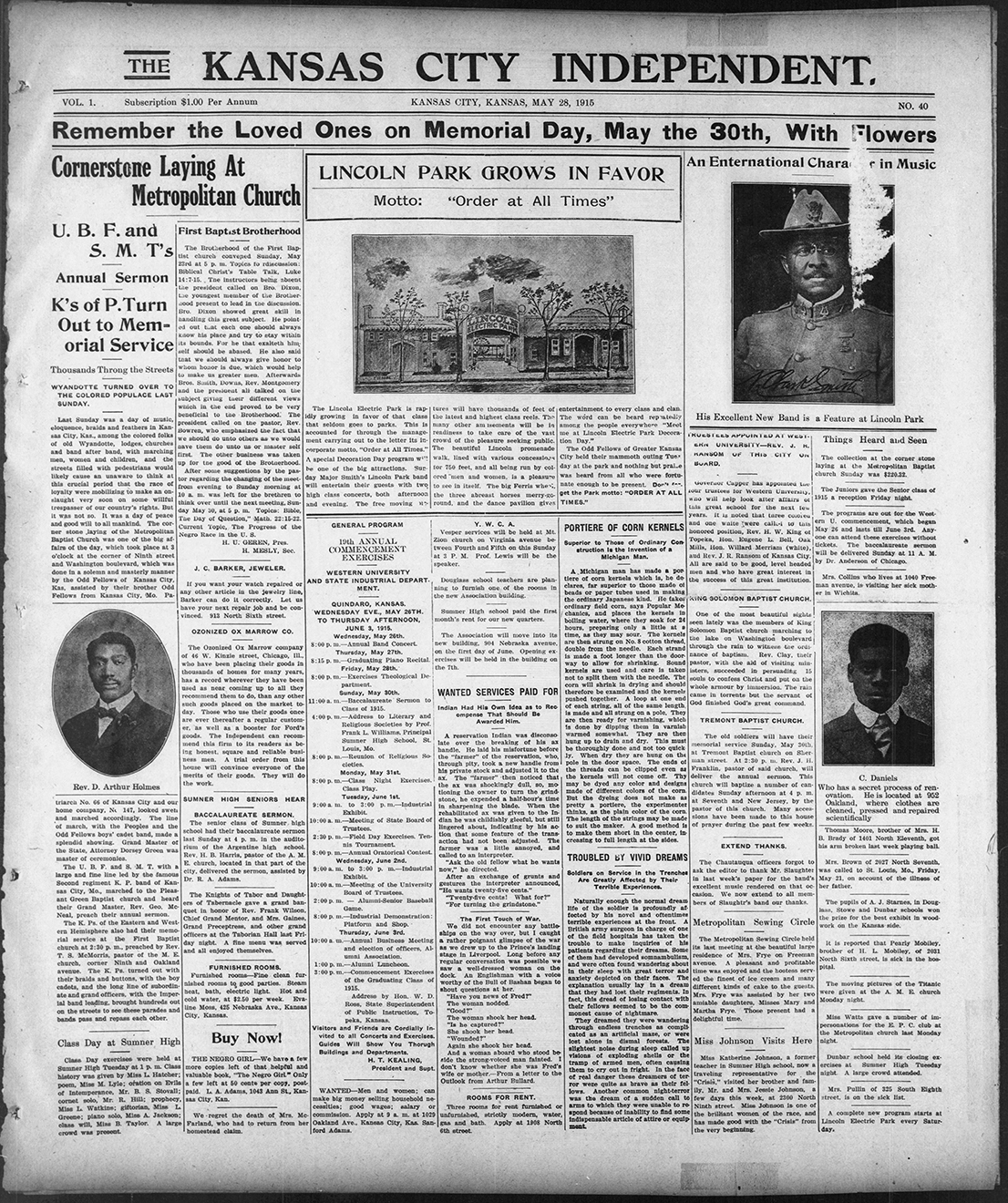

Lincoln Electric Park had an Eli Ferris wheel, a large, three horse abreast merry-go-round, a dance pavilion with a live orchestra directed by Major N. Clark Smith, and a 750-foot promenade of Black owned concession booths. An article in the May 28, 1917 edition of the Kansas City Independent stated that the park was swiftly gaining favor among patrons as “the” place to be and be seen. While an opening crowd of 8,000 might not seem notable by today’s standards, it was something to cheer about for the Black community.

“The success along any line is to give your patrons the best on the market and that is where I figure a big season for Lincoln Electric Park as my attractions booked are nothing less than stars,” said the General Manager of the Park upon the prospect of the upcoming 1917 season. The opening “figured conspicuously in the nation’s patriotism by raising the stars and stripes at 12:30 pm, followed by a few short patriotic speeches.”

The park’s life was short-lived however. 1925 Sanborn maps and city plat maps show no indication that an amusement park had occupied the site. The same 1925 map shows a row of commercial store fronts occupying Mayfield Avenue subdivided into two smaller residential plats. Mayfield Avenue was graded over sometime afterward, creating a larger, industrial use lot. Today the site is occupied by a beer distributor, a towel and linen laundry business, and an auto body paint distributor. Some quick calculations show that Mayfield Avenue would have roughly been where the entrance to the United Beverage parking lot.

Special thanks to Mr. Logan Thompson for clueing us in on the existence of Lincoln Electric Park and the role it played as a recreation destination for the city’s Black community. Additionally, the Black newspapers of the day, The Kansas City Independent, The Kansas City Sun and the Kansas City Advocate. Thanks also to the Missouri Valley Special Collections staff for their ongoing assistance and research in the crafting of our weekly historic postcard column.