Paul Thompson

Northeast News

Hickman Mills C-1 school district superintendent Yolanda Cargile sat at the edge of her seat during the City Council’s business session on Thursday, August 16, eager to hear the results from a years-in-the-making assessment of Kansas City, Missouri’s economic incentive policies.

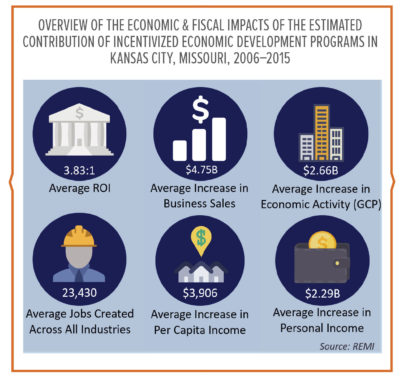

The City was triumphantly touting the new study, which shows a return of $3.83 in tax revenue for each dollar invested into incentive programs during a 10-year period between 2006 and 2015. The study was conducted by the Council of Development Finance Agencies (CDFA) for a cost not to exceed $350,000. The goal, according to a KCMO press release, was to examine “the historic impact of economic incentives on creating jobs, eliminating blight and generating new investment.”

Mayor Sly James praised the transformative impact of incentive projects in a press release announcing the study results.

“The information in this study helps ensure that future decisions regarding incentives are data-driven, not anecdotal, and shows how incentives have been essential in growing our city’s thriving economy and exciting momentum,” James said.

So Cargile watched with great intent. Those incentive policies, after all, incentivized health information technology behemoth Cerner to build a $4.4 billion complex at the former site of Bannister Mall. In the spring of 2016, the Kansas City Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Commission approved just over $1.1 billion in reimbursements over 23 years for the project, which was billed as the largest economic development project in Missouri’s history.

The Hickman Mills Board of Education initially voted against endorsing the project, though the district’s concerns were overpowered before the TIF Commission. Cerner agreed to set aside $8 million for the neighborhood surrounding its complex, with $6 million going to the Hickman Mills district over an eight-year window. Those funds are earmarked for specific uses, such as STEAM curriculum improvements, and are currently being held by the Economic Development Corporation (EDC) of Kansas City. Hickman Mills must submit proposals for spending those dollars to a three-person committee; if approved it then goes to the EDC for payment. As of now, none of the $6 million has been expended by the district.

Meanwhile, before this school year, Hickman Mills was forced to slice $3 million from its budget. That included transportation cuts, the closing of 19 teaching positions through attrition, slashed travel budgets, and a reduction from 175 days to 172 days in the student school year.

For Cargile, the district’s financial concerns remain permanently affixed at the forefront of her agenda.

“What changes can we make currently this year to try to offset the financial blow?” Cargile wonders. “There’s always this fear each year that we’re going to lose staff members to higher-paying districts.”

The story of Hickman Mills stands in contrast to that of the CDFA analysts, who were brought in to present the study to the KCMO City Council on August 16. CDFA highlighted a plethora of study findings from its executive summary, including an average increase of $4.75 billion in total business sales; an average increase of approximately $2.66 billion in economic activity; an average of 23,430 jobs created across all industries; an average per capita income increase of $3,906; and an average personal income increase of $2.9 billion in KCMO over the course of the study’s target window.

The story of Hickman Mills stands in contrast to that of the CDFA analysts, who were brought in to present the study to the KCMO City Council on August 16. CDFA highlighted a plethora of study findings from its executive summary, including an average increase of $4.75 billion in total business sales; an average increase of approximately $2.66 billion in economic activity; an average of 23,430 jobs created across all industries; an average per capita income increase of $3,906; and an average personal income increase of $2.9 billion in KCMO over the course of the study’s target window.

“The study shows that using incentives accelerates the rate at which assessed value increases,” said City Manager Troy Schulte in the press release. “The data validates that incentives work, and we want developers to use this data to take their projects into economically-distressed areas that need them the most.”

Not everyone at City Hall is viewing the study from such a rosy perspective, however. When City Council members were presented the data on August 16, a flurry of pointed questions ensued.

Alissia Canady, for instance, wanted to see data that compared growth in areas that received incentives to areas that didn’t. She also cited a recent white paper which suggested that a greater economic impact could have been realized by investing in start-up businesses, rather than business expansion. While Canady suggested that there are benefits to incentivizing development projects, she openly wondered after the presentation whether taxing jurisdictions are receiving fair value.

“This data does not provide sufficient information; it’s not conclusive in any manner,” Canady said. “I don’t think anybody can argue that we’ve had some benefit from how we’ve invested dollars historically. The question is, ‘Is the juice worth the squeeze?’”

To Canady, the main issue revolved around which entities were actually benefitting from the wealth generated by the city’s economic incentive program. What good is the program if it creates deficiencies in other vital areas?

“Now we’re trying to find ways to solve all of the deficiencies we’ve created in all those other areas: mental health, the school districts, the library, Metropolitan Community Colleges,” Canady said. “Everybody else is struggling, but we’ve got shiny buildings.”

Quinton Lucas expressed similar concerns, while lamenting the length of time that it took CDFA to complete the study. He also sought answers for whether blight remediation – a common rationale for incentive packages in Kansas City – was actually accomplished through the City’s incentives policies.

Lucas pointed out that Crown Center received a second Chapter 353 designation from this City Council. To get a second designation, Lucas argued, the implication would be that the first designation did not help the area achieve all of their policy goals.

Lucas wanted to know simply: “Did it work?”

The answer is complex. Certainly, money has been generated through the use of economic incentives; that much was clear in the CDFA presentation. Less certain, however, were the benefactors of that wealth. In other words, at what cost to services was that wealth generated?

At least one person in the room for the CDFA presentation has first-hand experience handling the unseen costs of the City’s economic incentive program: Hickman Mills superintendent Cargile. So when KCMO City Council members wanted to know if economic incentive programming in Kansas City is having a trickle-down effect on the those surrounding these projects, the question begs: what does Hickman Mills think about economic incentives?

There have certainly been some headaches along the way. Hickman Mills Finance Director Shellie Wiltsey detailed recent negotiations with the Jackson County Board of Equalization, an independent body tasked with establishing the assessed value of properties and handling any disputes that arise. Initially, according to Wiltsey, the Board of Equalization set an assessed value of $40 million for Cerner’s Bannister campus. Cerner disputed that figure, arguing that they shouldn’t be paying taxes on any of the buildings constructed after the TIF was agreed to. Ultimately, the Board of Equalization agreed, reducing the assessed value of the campus to $7 million.

There was only one problem: the Board of Equalization inadvertently left the value of the campus at $40 million when it assessed the value of the Hickman Mills district at $427 million in 2017. The $33 million overstatement – equivalent to $2.474 million to the district – left Hickman Mills scrambling to make up nearly $2.5 million in a budget that had already been slashed by $3 million heading into the 2018-2019 school term.

While Wiltsey was clear not to blame Cerner for the mishap, the adjustment has left the district trying to make up for a sudden 4% reduction in its general fund balance.

Following the August 16 presentation, the Northeast News inquired as to how the Cerner incentives have spurned economic development in the Hickman Mills area. Cargile noted that some new businesses and restaurants have opened around the Cerner complex, but added that the district is still waiting to see the full impact of those economic incentives.

“Would we have liked to see the tax payments for the assessed valuation of Cerner? Absolutely,” Cargile said. “We just reduced our budget for this school year, so you always think about what we could have done had we had that amount.”

Faced with similar issues, the Kansas City Public Schools (KCPS) Board of Education has created its own legislative priorities related to economic incentive reform. District spokesperson Ray Weikal hadn’t thoroughly reviewed the incentives study by the morning of Monday, August 20, but he did relay the KCPS Board of Education’s stance on incentive reform.

KCPS wants to place limits on the amounts of real property tax abatements and incentives that are allowed to flow out of public education and into non-education and for-profit economic development projects. In addition, the district is seeking repeals of existing legislation that allows economic development statutory boards to function with limited public school representation appointed to those bodies. Furthermore, KCPS is seeking legislation that will require representatives from the impacted K-12 institutions to be on those boards, while requiring votes for economic incentives to be approved by a super-majority.

“We believe that the entities that are impacted by economic development tax incentives should have more say in how those incentives are approved,” Weikal said. “Because we bear the brunt of these incentives, we should have more say in their approval.”

Though Weikal insisted that KCPS isn’t anti-development, he also acknowledged the strain tax incentives have placed on the district, which presently has approximately $200 million in facility maintenance and improvement needs that have gone unfilled.

“Our position is pretty clear: every year, approximately $25-$30 million in real property tax collections are diverted from Kansas City Public Schools because of economic development incentives,” Weikal said. “One of the things that we could do with that $25-$30 million per year is to help provide for universal Pre-K.”

Of course, not every development project in downtown Kansas City would have been completed in the same manner without economic development incentives, which is what left so many on the Council with lingering questions following the August 16 presentation.

“How can we use this data to ensure equity going forward?” Canady asked. “The response I got was, ‘Well, we don’t know.’”

Mayor Pro Team and 1st District Councilman Scott Wagner described the 10-year study as an important first step, though he also succinctly distilled the uncertainty that remains in its wake. While there is plenty of data piled into the complete CDFA report – more than 150 pages worth – it will also inevitably serve as a lightning rod for further inquiry.

“If you get a Cerner that pops up there, does the presence of that Cerner property raise the value of all of the properties around it that you didn’t incentivize?” said Wagner. “Therefore, were there actually more taxes generated to provide to Hickman Mills, or for any other jurisdiction?” “I think what you heard today was, ‘we don’t know.’”

According to the City, the study represents a step towards unprecedented transparency in Kansas City. Though the process took longer than expected, the City’s press release suggested that the end result effectively yielded three studies for the price of one: 1) An economic impact analysis using only KCMO data; 2) A geographic analysis using tax data from overlapping taxing jurisdictions; and 3) A process improvement analysis with recommendations to enhance data collection, data management and reporting incentives data for the future.

Moving forward, CDFA recommended that KCMO provide annual updates, rather than a 10-year retrospective. CDFA also recommended incorporating incentive data on KC Stat, tracking and reporting actual performance data separately from projected performance data, and hosting community forums to identify other economic indicators to track.

Ultimately, the legacy of the economic incentive study is likely as a baseline for the City as it moves forward with economic incentive policy.

“I’ve found that every piece of information is used to verify everything. Will someone refer to this? Maybe. Will the jurisdictions say, ‘You haven’t proved the validity of the programs?’ They could,” Wagner said. “But something is better than nothing.”