Michael Bushnell

Publisher

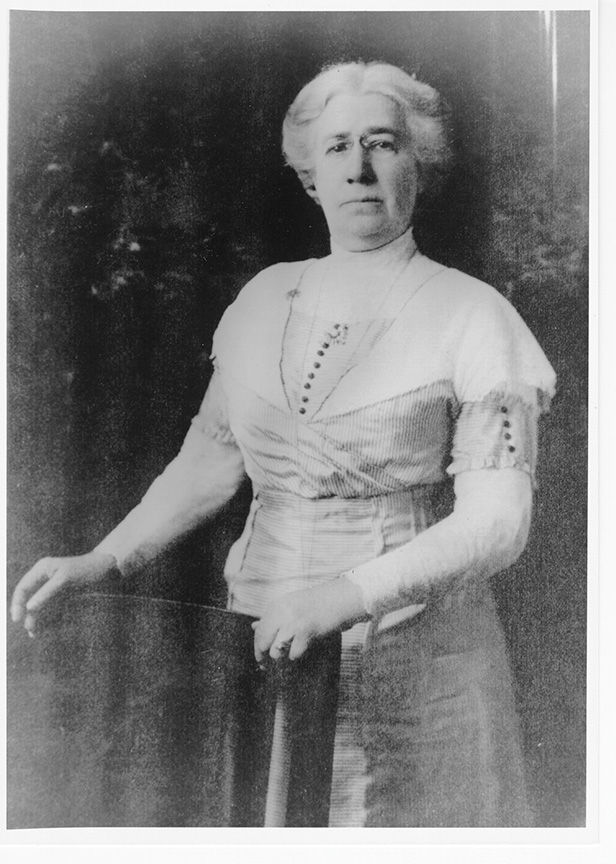

Born near Lexington, Ky., on June 6, 1843, young Leannah Loveall would go on to live a long and very interesting life, laced with tragedy, several dust-ups with the law, a conversion to Christianity at an advanced age and ultimately, donating the property that would eventually become today’s City Union Mission.

At a young age, Leanna wanted to participate in a parade in her home town that honored Abraham Lincoln, who happened to be campaigning in her town. Without her father’s knowledge, Leanna crafted a colorful yellow dress, stole her father’s horse and rode in the parade. This enraged her father, who was a staunch Southerner, and he immediately gave Leanna the boot from the family house.

She took up with an aunt for a period of time then began teaching school. She was courted and eventually married a man, much older than her, named William Chambers. The union, however, was fraught with tragedy as both of her children were stillborn and Mr. Chambers was killed in a buggy accident.

One of Leanna’s childhood friends had taken to working in a house of ill fame in Indianapolis and wrote her to come there for work in that field under the name Annie Chambers.

“I believed everything was against me,” she said in an interview for the Kansas City Journal Post in 1932. “I decided to go to Indianapolis and have a short but fast life, and a merry one. When I arrived, I asked the hack driver to take me to the best ‘resort’ house in town. He did and I became a member.”

Indianapolis was kind to Chambers and soon she had her own operation. A police raid, however, forced her to think of a different location for her Bordello. Two of her girls were from Kansas City and told of good prospects in the growing frontier town. Once again, Annie was on the move.

In the late 1860’s, Kansas City was known as a wide open boom town. With a population of roughly 50,000, mostly single men engaged in the cattle or railroad trade, spelled instant success for Chambers. Another plus, the city didn’t have an organized police force until 1874 and the prospects were even brighter.

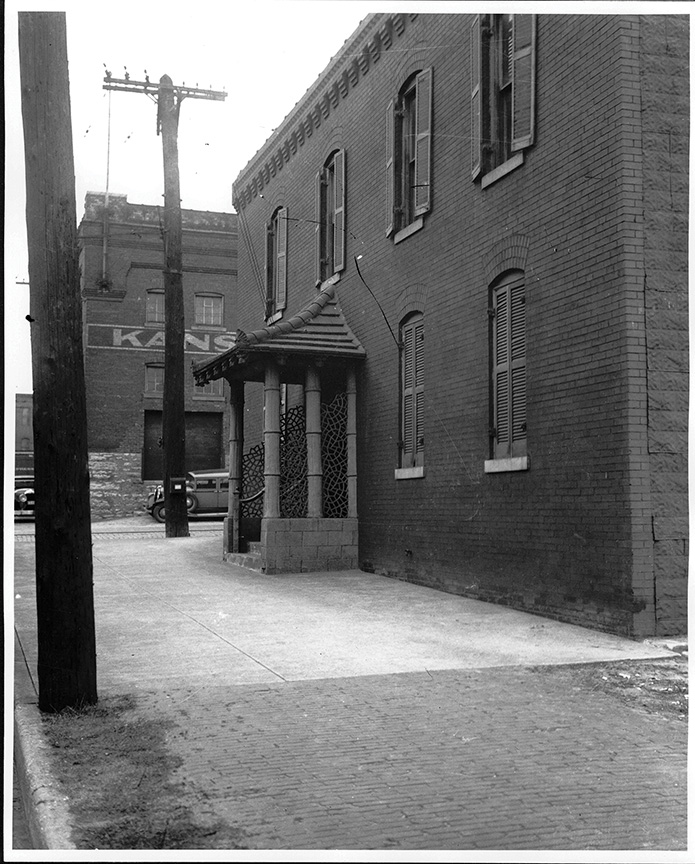

Chambers was already an astute businesswoman, and upon arrival in Kansas City in 1869, she set up shop on the north side of the river near present day Harlem. Business was so good that she soon had saved enough to build her own house in the City Market area at 201 W. Third Street. Her 25-room mansion was built within a stone’s throw of two other highly reputable “houses” on the same corner, Madame Lovejoy’s just to the East and Eva Prince’s on the Northwest corner of Third and Wyandotte.

The Chambers house was a literal palace among the other houses of ill repute in the district. In the entryway, the name “Chambers” was laid out in marble tile. A large, leather settee was in the parlor where large paintings of women in gilded frames adorned the walls. In the center of the parlor was a large, circular red sofa where her girls would “court” their guests, and at the foot of the stairs, a filigreed trim piece with Chambers’ initials hung from the ceiling.

For 40 years, business was booming, despite their close proximity to the new city hall and new county courthouse built only blocks away. Chambers, however, kept the politicians’ hands well greased in order to continue operations, even during a time when police raids were the norm, rather than the exception. Chambers, however, didn’t run a second rate operation. She often bragged later in life that many of her girls found fine husbands, largely because she impressed upon them manners and social skills. While other “resorts” – as she referred to them – charged as little as 25 cents for their services, Annie’s minimum charge was $10.00, her girls keeping half. Wine was offered, as well, but never whiskey. Wine sales sometimes topped $700 for a single night at $5 a bottle.

Times inevitably changed and in 1913 a new city government was elected on the promise of cleaning up the out of control prostitution plaguing the city’s red light district around market square, where over 47 brothels operated. Unlike the three upper end operations at Third and Wyandotte, most of these were not the higher end operations, treating the girls poorly and using them as merchandise.

Chambers kept her operation going, but soon the bribes were not enough. In 1923, Chambers went “legit” and transitioned to operating a rooming house for railroad workers and drovers. Immediately next door, the Madame Lovejoy resort house was sold to Frank Ennis, a coffee merchant and leased to Reverend Bulkey and his wife, Beulah.

One afternoon, one of the area’s working girls from the Prince House knocked on the Bulkey’s door, weeping uncontrollably, asking if the reverend would perform a funeral for her deceased infant. It was during this service, listening to Bulkey’s sermon through her windows, that Annie converted to Christianity. She was quoted in the 1932 Journal Post article as saying it was the first sermon she remembered hearing in her 75 years and she broke down in tears.

She soon approached the Bulkeys and sold her property on the provision that she be allowed to stay until her death and that she be provided with food and shelter.

In her twilight years, Annie often gave tours of her house to curious people wished to see what a house of prostitution looked like. During those tours, she often spoke to her guests about the evils of prostitution and its effects on society, often helping other working girls get out of the profession.

“Isn’t it strange that in this house where so many women have led a life so far from what was right, now I, the worst of them all, have turned the place in to a mission for the saving of just such women and am preaching to them the gospel of salvation,” Chamber said.

On March 24, 1935, at the age of 92, Annie Chambers passed away in her house, lying in the huge brass bed she had purchased for the house almost 50 years before. At her funeral, conducted by Reverend Bulkey at the City Union Mission, flashily dressed women sat next to those wearing the uniform of the Salvation Army. Ragged, disheveled men from the mission stood next to prosperous businessmen of the city, all with their own memories of Annie Chambers. She is interred in Elmwood Cemetery.

The Bulkeys inherited the Chambers property and used it as part of their City Union Mission next door. The mansion was razed in 1946.

Source Material from “Voices Across Time: Profiles of Kansas City’s Early Residents” by Dory Deangelo, Kansas City Public Library, and Missouri Valley Special Collections.