Kansas City tenants are 19 times more likely to be evicted if they live east of Troost, according to new research conducted by the Kansas City Eviction Project.

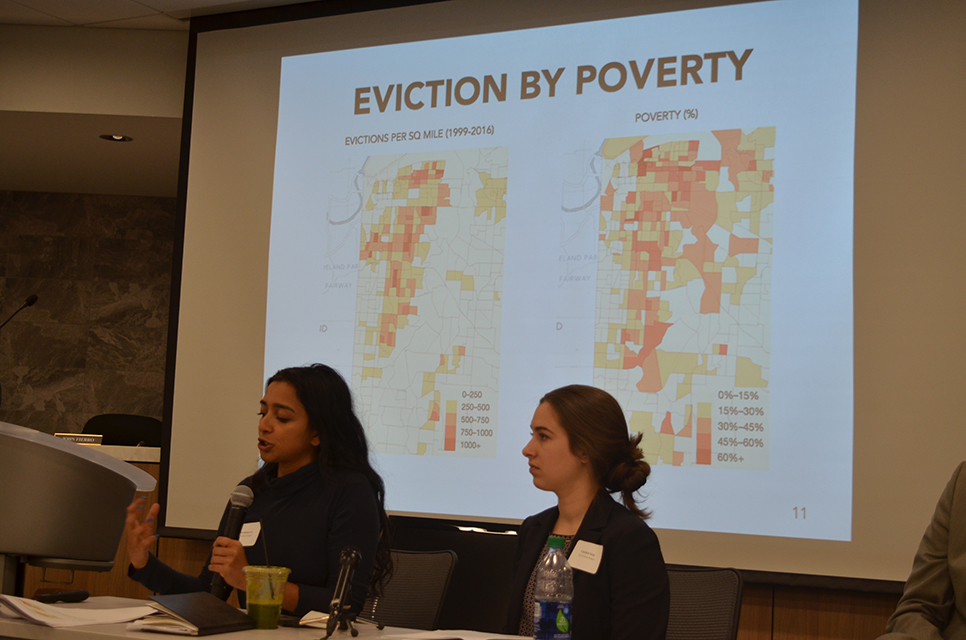

Researchers with the organization unveiled alarming data during a special forum convened at the Kansas City Public Schools headquarters on the afternoon of Thursday, March 15. Internal mobility data from KCPS was combined with case-level data from Jackson County eviction court as part of the preliminary study.

The analysis showed that every year, somewhere between 20% and 30% of students transfer into the district, while another 20% to 30% of students transfer out of KCPS. What’s more, the data showed that 40% of KCPS students don’t remain enrolled in the same school for the entirety of an academic year. One cause of the high mobility rate, research shows, are evictions. Roughly 4% of KCPS students experienced a formal eviction – evicted through a court of law – between 2008 and 2012.

The stark contrast in eviction data on either side of Troost was readily apparent in a series of heat maps presented by the Kansas City Eviction Project. Though population per square mile appeared relatively balanced, evictions per square mile – along with the percentage of people living in poverty and Kansas City’s black population – skyrocketed east of Troost.

KCMO Mayor Sly James said that the Kansas City Eviction Project team has already produced some “amazing data” with its initial findings.

“While we’ve been working on ways to address student mobility since 2015, we’re only now starting to have the data and the analysis to be able to understand how eviction is an issue in this city,” James said. “The harmful effects of eviction are clearly a part of a student’s performance in the classroom. Imagine if you come home one day, and all your stuff is on the street. Now you’re spending the rest of the night and the next day and who knows how much longer trying to find a place to stay. You would have to be the single most dedicated, focused, mature student to be able to focus totally on your classroom studies and academic behavior while there is absolute disruption in the basic necessities of life.”

Kansas City Eviction Project’s Tara Raghuveer is a Harvard-educated researcher who has been studying eviction in Kansas City for the past five years. Raghuveer presented the organization’s findings during the March 15 forum.

“Really, this is the issue that keeps me up at night,” Raghuveer said. “I’m totally obsessed with it.”

That obsession has led Raghuveer to spend hundreds of hours over the past few years in landlord/tenant court, watching eviction cases. Approximately 72% of the 106,000 eviction summons filed in Jackson County between 2006 and 2016 ultimately made it into a courtroom. By the time those cases get into court, Raghuveer found, the result was practically preordained: 99.8% of the time, the tenant is evicted. It’s no wonder, then, that tenants appeared for those court dates just over 30% of the time. And these are just the formal evictions: Raghuveer suggested that there are countless more families confronted with eviction in less formal circumstances.

“In my qualitative research in Kansas City, it became clear that the data from the courts do not represent informal evictions that happen outside of the court system, with no data to represent them,” Raghuveer said. “Forced moves, even when they’re not mandated by the court, can also be considered evictions.”

To illustrate her point, Raghuveer described one example of an informal eviction she came across in her research. In this case, a woman moved into a fully furnished apartment. When she fell behind on rent, however, the landlord removed the furnishings from the apartment without permission. Included among the removed items was a refrigerator which still contained the tenant’s food.

“It’s illegal, but it happens,” Raghuveer said.

Every year, roughly 9,000 formal evictions are filed in Kansas City. In total, Raghuveer and her team have scraped data from 182,992 eviction filings spanning 18 years, drawn from Jackson County court records. Similar data from Platte and Clay counties weren’t included, however, and informal evictions aren’t quantified at all. According to the Kansas City Eviction Project, this means that the true toll of eviction is likely far greater than the statistics surrounding court-ordered evictions might indicate.

“This is not a comprehensive story, by any means, of all the evictions that are happening in Kansas City outside of the courts, with no data to represent them,” Raghuveer said.

According to Raghuveer, the threat of eviction has become a fact of life for low-income Americans. These evictions are closely tied to affordability. In today’s America, a minimum wage job simply can’t support a family.

“In 2018, a person working full-time at minimum wage cannot afford a two-bedroom apartment in any county in the United States,” Raghuveer said.

Roughly 40 evictions are filed every day in Jackson County, and Raghuveer has found that for some landlords, eviction has become a business practice.

“There are some new players on the scene in terms of landlords that kind of mix up this story of how eviction impacts our community,” Raghuveer said. “Some of the biggest evictors now, relative to 10 years ago, are out of state property managers. They’ve been buying up single family homes and rental properties across the city. That’s led to massive churn.”

What the researchers need now is more data to help them piece together a clear picture of where students go when they’re evicted, and how the toll of eviction impacts academic achievement. Raghuveer and her team have already partnered with KCPS and Independence public schools to mine that data, and are currently working on new data-sharing agreements with Fort Osage, Grandview and North Kansas City. Hickman Mills representatives, among others, were also in the audience for the March 15 presentation.

Kansas City Eviction Project’s Carolyn Stein said the preliminary data shows that academic success is less common at schools where eviction rates are highest. Stein called the work of understanding the link between eviction and achievement “the last piece of the puzzle” in the team’s research.

“Some schools have up to 8% of their students facing eviction,” Stein said. “Schools where students are very likely to face eviction are the schools where the standardized test scores are lower. It’s certainly suggestive and I think deserving of a lot of further research.”

To that end, the Kansas City Eviction Project is making a formal request for new data to help paint a more complete picture. They’re asking for 10 years of data from school districts: student core files, attendance files, DESE assessment data, discipline files, home addresses and parent/guardian names. That way, school district data can be matched to court data with greater certainty.

Stein noted that the organization will take pains to protect the data.

“Personally identifiable information will not be disclosed,” Stein said. “The data will be kept in a secure, password-protected remote server, and the data will be destroyed at the conclusion of the study.”

The City of Kansas City, Missouri is eager to dive further into the topic of eviction. Kate Bender, Deputy Performance Officer with the City, marveled at the data compiled by Raghuveer and her team.

“I was certainly blown away by the research she’d done and the perspective she’s bringing to us,” Bender said. “And also, not to say that Tara herself isn’t amazing, but the data is also really, really amazing.”

“It’s a data set that I don’t think we really knew existed in any form,” Bender added. “It’s not a heavily researched issue across the country, so I don’t think Kansas City is alone in that respect.”

At the conclusion of the presentation, Mayor James urged school districts in attendance to hop on board with the data-sharing efforts needed to build a more comprehensive picture of evictions in Kansas City. Though efforts have been made to pull data on a statewide level, James warned that it could be a long wait for that information.

“If you’re going to wait around for the state to do something, then you’re going to be waiting around forever,” James said.