By LESLIE COLLINS

Northeast News

February 27, 2013

Angela Richmond cried when she learned the Kansas City Municipal Drug Court (KCMDC) lost its funding for transitional housing.

Seventy-five percent of the drug court participants are homeless when they enter the one-year long program and transitional housing plays a critical role in the success of the program, said Richmond, a Drug Court case manager.

When the KCMDC began offering transitional housing in 2007, thanks to a grant, the program’s success dramatically increased. Prior to the housing component, slightly more than 40 percent of individuals successfully completed the program. With the addition of transitional housing coupled with case management services, the success rate rose to 65 percent, she said.

Now, the grants have expired and funding ran out Feb. 1, 2013. KCMDC applied for additional funding but to no avail. Due to tighter municipal budgets across the U.S., grants are becoming more competitive, said Drug Court Coordinator and Probation Manager Stephanie Boyer.

Representatives from the Drug Court presented their dilemma during the city’s Feb. 20 Public Safety Committee meeting and requested the city assist with funding.

Within the past three weeks, Drug Court employees have already witnessed the detrimental effects from losing transitional housing, said Joe Locascio, Kansas City Municipal judge in the 16th Judicial Circuit. Participation in substance abuse treatment has decreased, reporting to Drug Court has decreased, positive drug screens have increased as well as new arrests and charges, he said.

A significant number of Drug Court participants hail from the Historic Northeast, Locascio told Northeast News.

“Now, we’re in a situation where we have chronic offenders who have maybe 60 days of clean time who are now being forced to go back out on the street or are couch surfing with relatives, which really undermines their recovery and undermines what we’re trying to do with this population,” Locascio said. “Since many of them are chronic offenders, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see they’re going to end up back in jail, and they do.”

Drug Court history

Established in 2002, KCMDC is an “intensive court-supervised comprehensive treatment program” targeted at individuals charged in Kansas City, Mo., who display signs of a chronic and severe substance abuse problem. Those chronic users have abused substances anywhere from 11 to 40 years, Locascio said. The youngest age they accept is 17. Admission to the program is voluntary and participants must have plead guilty or have been previously found guilty and must accept a 180-day sentence at the Municipal Correctional Institution. Participants must also attend an in-patient treatment facility for 21 to 30 days and be placed on probation for two years. Following in-patient treatment, participants must complete outpatient treatment, attend a minimum of one substance abuse group meeting per week, submit to random drug testing, check in to court on a regular basis and adhere to directives from the Drug Court coordinator, treatment counselor and Drug Court judge, among other requirements. Transitional housing is another component, which provides 24/7 supervision through a house monitor and keeps participants accountable.

“I have great communication with them (house monitors). If anything goes wrong, if anyone is breaking any type of rule, they let me know immediately,” Richmond told Northeast News.

In addition to accountability, the housing provides a safe place to relax and establish a new, normal routine, Richmond said.

Currently, Drug Court serves 70 participants and of those, 51 percent lack a GED or high school diploma and 38 percent are living with a mental health issue. Without transitional living, those issues further hinder a participant’s recovery.

“Transitional living is such a critical piece and we truly believe in it. I cried pretty hard. I really did,” Richmond said of her reaction to the funding loss. “It was a very bad day. As soon as I told the clients, some of them just starting crying immediately. I cried and held them. I hugged my clients and told them we’ll try to figure something out, to not give up. But, they were devastated, devastated. All they kept asking me was, ‘Angela, what am I going to do and where am I going to go?’”

That’s a question Richmond is desperately trying to figure out. Dismas House of Kansas City, which offers outpatient treatment and recovery support services, is providing housing vouchers, but those only last up to six weeks, Richmond said. ReStart is also providing transitional living, but beds are scarce and turnover is slow, she said. She’s also trying to secure Section 8 housing vouchers, but those are also “hard to come by.”

Some individuals are moving in with friends or significant others, but it’s not an ideal situation, she said.

“They’re just coming up with these random people (to live with) and it doesn’t work. Some people have ended up right back in jail,” Richmond said.

“We are in an emergency situation,” Locascio said. “We desperately need to keep this population in transitional living. Our numbers in Drug Court are now increasing. We’re getting really good now at identifying the chronic offender.”

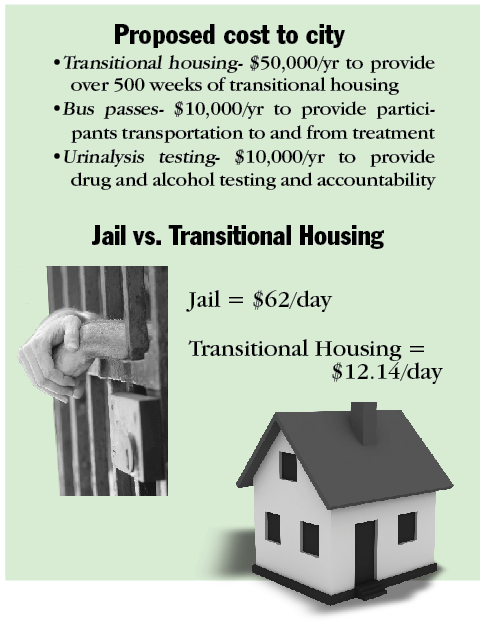

When these individuals reoffend, it costs the city resources and money, Locascio said.

Locascio used the example of John, who police arrested 50 times in Kansas City in 2011. Within a 40-day period, EMS personnel transported John to the hospital 21 times because he was highly intoxicated. Within a 40-day period, Truman Medical Center saw John 35 times for intoxication and he was admitted to detox 23 times in 2011. The average cost of each arrest was $1,060, which adds up to $53,000 for John. His EMS transports totaled $21,000, his ER visits averaged $56,000 and his detox visits in 2011 alone cost $23,000. John’s total cost to Kansas City is $153,000.

Kansas City Police Department Officer Nathan Kinate submitted a letter to the Drug Court requesting that John be placed in the program.

“Every time he is transported he occupies the time of two police officers, a paramedic, an EMT, and many times a KCFD pumper crew (at least four firefighters) for approximately 20-40 minutes while on scene,” Kinate wrote. “Once transported to the hospital there are several staff members that have to tend to his condition.”

John participated in the Drug Court program, which only cost the city $6,550, which included jail time, substance abuse treatment and six months of transitional housing. John has now remained clean and sober for one year and currently serves as a house monitor at Isaiah’s Place. Richmond said there are plenty of success stories and another includes a 41-year-old man who used cocaine for years and recently celebrated his one-year anniversary of being clean. He now works at a local BBQ joint and is attending barber school. One woman is attending college at Penn Valley and has been sober for at least two years and another young woman has been sober for a year and still calls and visits the Drug Court staff, even though it’s no longer a requirement for her.

City Council member Michael Brooks said he’s hopeful the city will be able to secure funding for transitional housing, even if it requires seeking out community partners.

“You’re going to spend the money one way or another,” Brooks said. “It makes sense to spend it on treatment and housing rather than detox and arresting.”

City Council member Scott Taylor agreed and said it’s a “pretty clear cut choice.”

“The program has worked, it gets results – we’ve got documentation,” Taylor said. “It’s just a matter of finding money to invest.”