Michael Bushnell

Publisher

Making the floods of 1903 and 1908 seem insignificant in comparison, the flood of 1951 was dubbed “The Great Flood” with the local mantra, “May there be no next time.”

Souvenir booklets and postcard folders were published about the ‘51 flood by enterprising area photographers and authors like Jo Anne Graddy, who self-published the photo essay booklet entitled “The 1951 Flood in Greater Kansas City: A Picture Review.”

Another was “Flood Disaster Kansas City, 1951,” published by Warner Studios of Kansas City. Warner Studios also published a postcard folder with the same title. The description inside reads, “This is the story of the Flood of July 1951, the costliest in the nation’s history, over three-quarters of a billion dollars-worth of destruction.”

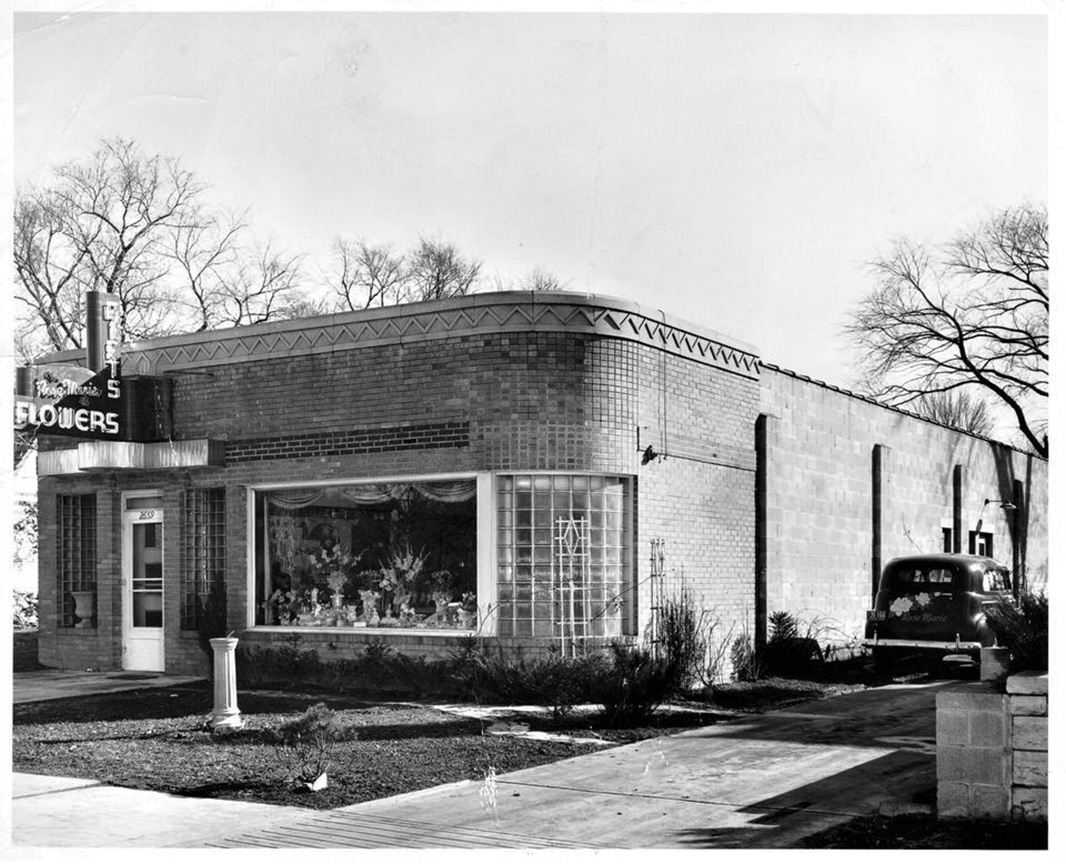

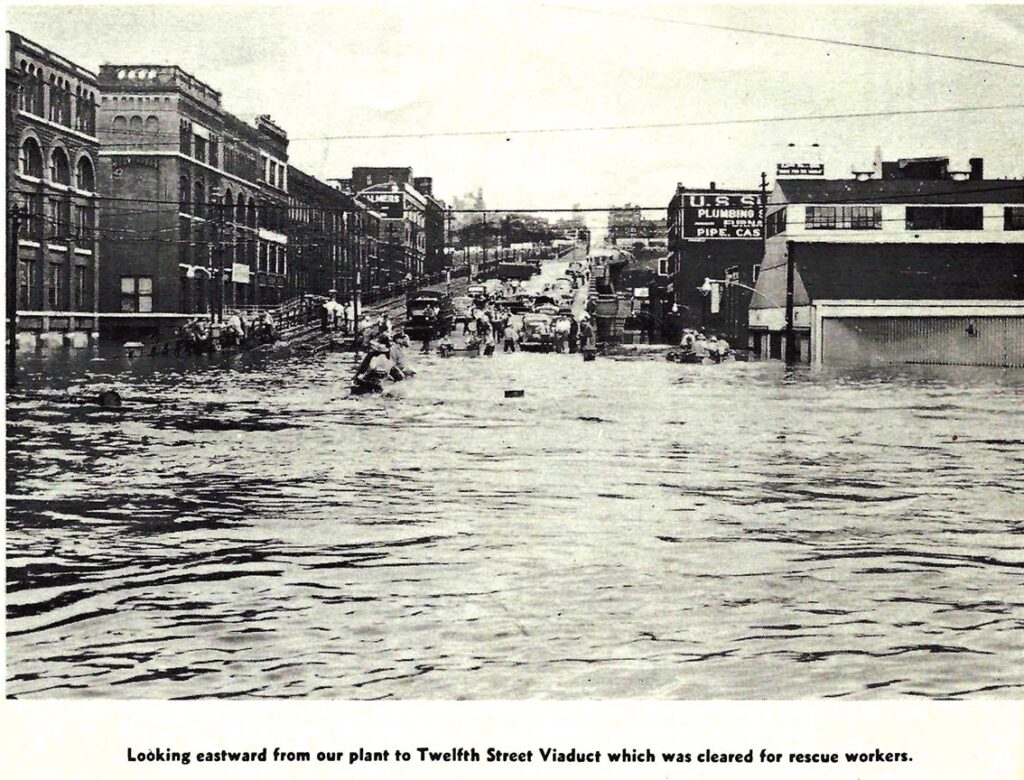

Columbian Steel Tank Company, located at 1401-1701 E. 12th St., also published a booklet that covered how their business and employees fared during the flood. (see image above) Company President Joseph M. Kramer penned a moving forward to the 16-page photo booklet that offers an extensive view of the flood both outside and inside of their manufacturing facility at the foot of the 12th Street Viaduct.

It is a story dramatized by hundreds of thousands of individual tragedies: by homes and belongings being swept away in the flood waters; by thousands of railroad cars lifted off the tracks and slowly moving downstream like huge battering rams; by huge accumulations of debris against rail bridges obstructing the flow of water; by cattle and livestock swimming aimlessly in the swollen waters in the stockyards district; and by submerged bridges, highways and buildings.

The July 1951 floods were caused by a huge storm of unusual size and intensity for the central Great Plains. Excessive rainfall in central and western Kansas during May and June of 1951 caused major flooding and saturated the soil, sapping its capacity to absorb any additional rainfall.

On the afternoon of July 9, the rain began to fall heavily and continued through the morning of July 10. Following a brief lull, rain began again the evening of July 10 and continued through July 12. By midnight July 13, unprecedented amounts of rain had fallen since the beginning of the storm.

An excerpt from Kramer’s forward to the Columbia Steel Tank flood booklet reads: “‘Black Friday’ the 13th, July, 1951, Time: 11:20 a.m., Place: The concrete flood wall on the Missouri side of the Kaw River, man’s puny barrier protecting the Central Industrial District of Kansas City from a flood swollen torrent. Here at a point where the Santa Fe Railroad cut the dikes, a sandbagged gate suddenly gave way and the great Kansas River roared through the opening, then sloshed over the revetments to its juncture with the Missouri.”

The break sent a wall of water three feet high cascading northward down Genesee Street at 15 miles per hour. Four hours later, the water was over 15 feet deep. Later that night, it had risen to a depth exceeding the Great Flood of 1903 by over five feet.

Some workers had less than 20 minutes to clamor to a higher spot, some climbing out building windows and heading up the fire escapes for refuge. More than 15,000 residents trod from their homes in a ragged line with whatever belongings they could carry as flood waters swirled around their ankles, then knees, and ultimately inundated the entire district.

Armourdale came next, then the Central Industrial District, and then the Fairfax area and Riverside. Some people fled to relatives and friends; others took advantage of the emergency shelters hastily set up by the Civil Defense and the Red Cross. Along Southwest Boulevard, floating petroleum storage tanks from the Southern Oil Company sparked fires at Schutte Lumber Company and the Battenfeld Grease Warehouse.

By comparison, the ‘51 flood outpaced the Great Flood of 1903 by over 15 feet, with the Kaw River cresting at over 42 feet above normal. Both were outpaced by the 1993 flood that crested at 49.6 feet.

For an in-depth look at the 1993 flood, visit the new exhibit at the Kansas City Museum entitled “Documenting a Disaster: the Flood of 1993 Through the Lens of Kenneth L. Kieser,” on view from July 6 to October 22. This exhibit is a 30-year look back at the flood of 1993 through the lens of outdoor photographer Kenneth L. Kieser and his images of areas hard hit along the Missouri River. This exhibit compares the flood to others in Kansas City’s history over the last 175 years and describes the unique weather events that led to the flood. Mostly on view are over two dozen remarkable photos that remind us just how powerful Mother Nature can be.

The exhibit is free to the public and is located in the Meeting Room & Education Space on the third floor of the Kansas City Museum.