Abby Hoover

Managing Editor

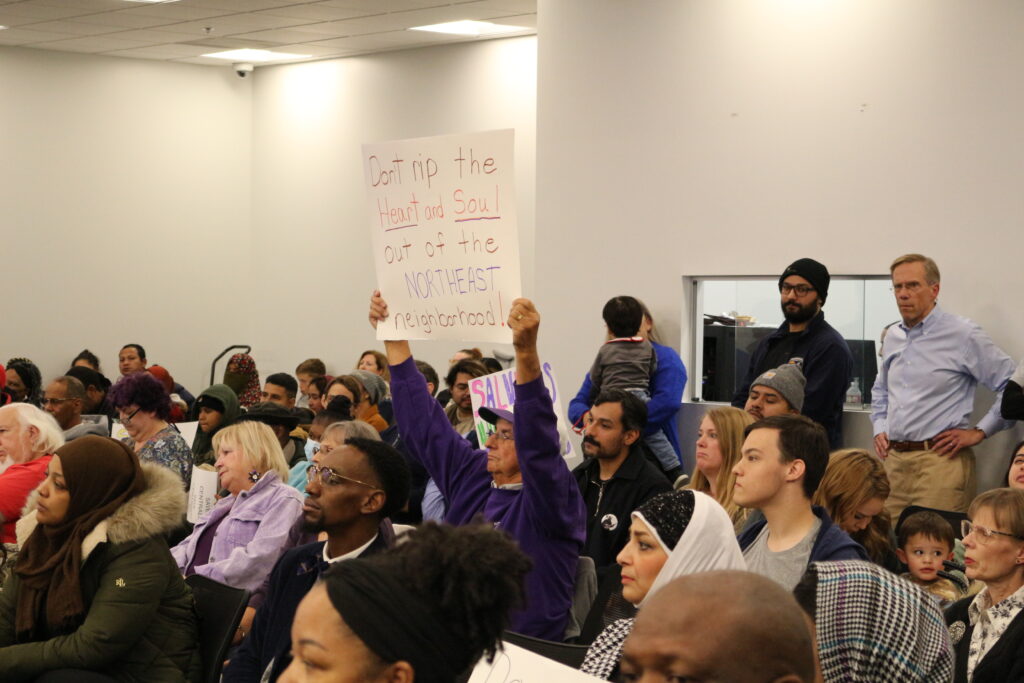

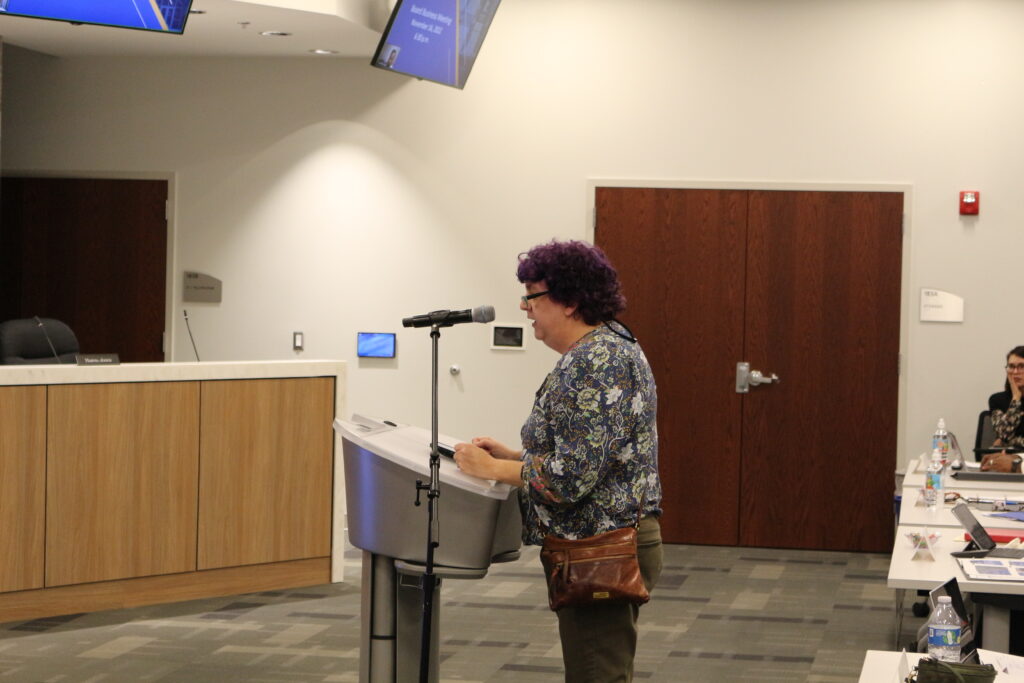

Northeast community members showed up in force to last week’s bi-monthly Kansas City Public Schools’ (KCPS) Board of Directors meeting to oppose proposed school closures.

Blueprint 2030 will serve as an update to the KCPS 2018-23 Strategic Plan and guide the district’s work over the next decade by outlining five and ten year goals. Following Community Chats at three locations in Northeast, neighborhood leaders, stakeholders, teachers, parents and community members, stepped up to fight the closures.

A Lincoln College Preparatory student kicked off the lively public comment session by asking the Board not to close her former school, Central High. She noted the vibrant sports programs that encourage strong academics, the dedicated band teacher who personally lent her a saxophone, and the many mentors and advocates who support the students. She also recognized the school’s struggles, including the loss of their debate team, and fights with other schools.

“You’re just not another person, but you are like a family,” the student said. “The reason why the board wants to keep Central open is for the amenities like the pool and the indoor track, but those students are so much more than just the amenities there, and they deserve to be able to stay in their school and feel safe there.”

She shared that she could walk to Central, but has to take the bus to Lincoln. It has given her the insight that if Central closes and a student misses their bus to their new school, their education could be impacted.

“We already have a bus shortage in Kansas City, so how are you going to deal with all those students getting back and forth?” she asked.

Larry Cooper, a 2016 graduate of Northeast High School and a committee member for Mattie Rhodes Center, spoke on behalf of the alumni association, which has been very involved in the fight to keep their alma mater open.

“I am one of the many success stories for Northeast,” Cooper said. “A lot of people think that just because Northeast is in the ghetto, not a lot of people can come from there and be successful, but I am one of those.”

Since the 1990s, the Northeast High School Alumni Association has given over half a million dollars of scholarships to the school’s students.

“I don’t think any other alumni association is as active or as involved in our students than we are, so we are disappointed to hear that you want to close our school, considering we give back more than anyone else does to our students, to our food pantry,” Cooper said. “Our food pantry supplies over 100 families, which are primarily minorities, and again, closing that would mean those families don’t get that food.”

The alumni association is opposed to closing any schools in Northeast. James Elementary in Indian Mound and Whittier Elementary in Lykins, which Cooper noted are both high performing, are also being considered. He does not want to see those students bussed to different schools out of the neighborhood, and he asked for the cost the district would have to pay to bus them.

“The culture of the Northeast neighborhood, as you can tell, we’re primarily Hispanic, but we also have a lot of Muslim and other African American students in our community over there,” Cooper said. “Quite simply, if you close our schools, you will show the Northeast community that you would rather build elsewhere, invest elsewhere, than take care of the students in our community.”

Cooper added that the district should not be working to bring back students who fled to the suburbs.

“I know the buildings are old, Northeast was built to stand for 500 years, we’re 109 years into it standing,” Cooper said of James. “It has done many wonderful things. We have a brand new football field that the Kansas City Chiefs bought us in 2017 and now all of a sudden we just want to get rid of Northeast High School. We ask that you guys take the time and realize that you should delay the vote. That it is not time yet to vote. We ask that you wait for a permanent superintendent and a permanent school board.”

Cooper closed, saying he was extremely disappointed that Board Treasurer Manny Abarca, a resident of Indian Mound, is willing to close any of the schools in his neighborhood that he represents.

Gregg Lombardi, executive director of the Lykins Neighborhood Association, spoke in opposition to closing Whittier.

“I’m here on behalf of the 4,000 residents in Lykins, asking you, strongly urging you, to keep Whittier open,” Lombardi said.

“We’re in one of the lowest income neighborhoods in the whole city, 62% of our children speak a language other than English at home, there are more than 15 languages spoken in Whittier, and yet the school has some of the highest academic performance in the whole district,” Lombardi said.

Using the district’s statistics, he pointed out that Whitter is at 82.1% Academic Progress Rate (APR), versus an average 67.9% for the district, and James Elementary is also high at 85% APR.

“It doesn’t make sense to close schools that are your highest academic performing schools in really challenged environments,” Lombardi said.

Lombardi showed the board on a graph that there is a serious flaw in the statistics that the school district is using as a basis to close the school.

“They’re telling us that there’s this trend downward in enrollment, and they’ve given us this chart, which shows a trend downward at the start of the school year, but this is not the most recent data,” Lombardi said. “As of today, there are 375 students in Whittier Elementary school, the school’s at 93% capacity and is now on track to be at 100% capacity by the end of the school year. Again, it just doesn’t make sense to close down a school that is performing so well and will be at 100% capacity.”

Lombardi said if a school needs to be closed down in the Northeast, it should be Garfield Elementary, which he showed is one of the lowest performing schools in the district at 45% APR.

“The school district could mothball Garfield and when the bond passes, instead of using $20 million to build a school – a new school that nobody needs – you could remodel Garfield and turn it into an excellent school for maybe $8 million,” Lombardi said. “So save lots of money, don’t shop for kids all around to different schools back and forth, preserve the best schools that you’ve got in the system. So listen to us, please, and work with us. We, together, can come up with a great plan to make our schools better without damaging the students and without damaging neighborhoods.”

Kate Barsotti, president of the Columbus Park Neighborhood Council, shared her perspective as a leader in a neighborhood with no schools left. Today, they have a hard time attracting families, and she envies her neighbors to the east.

“The Northeast needs support,” Barsotti said. “The greatest vote of confidence comes from keeping, not closing, these schools. Please delay this decision until a new superintendent can lead us forward. I know what it’s like to live in a neighborhood that has little hope of attracting families. We don’t have enough to offer. The Northeast still does. If you close these schools, you’re making a generational change. Families will not adapt, they will leave.”

Rebekah Wampler, a 5th and 6th grade English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher at Whittier, has been at the school for nine years.

“It is good to look at history and see where injustice has made a deeper wedge between the community and the district,” Wampler said. “I don’t need to tell you that even though over 60% of our population is ELL [English Language Learners), we still hold firm in our numbers.

“When I came to this district, I had a 10-month-old baby on my hip and a handful of garage sale items to set up my classroom,” Wampler said. “The faculty and the families at Whittier helped me get ready for my 34 students. They tended to my child while I hung bulletin boards and sharpened pencils.”

Wampler said her students have changed her. They taught her languages and phrases so they could help one another, shared meals and stories.

“When students change grades, the teachers here sit down, discuss strategies that work, details about the children’s personalities, so we can better welcome our students into our new classroom,” Wampler said. “We become a community that grows stronger, no matter the differences or the difficulties. This is about looking out for our families we serve in the best and most efficient ways possible. As a district we constantly push the phrase to do what’s best for our students. We do our best. We do our absolute best to keep students at the center of every topic. So let’s do that.”

There are 15 languages spoken at Whittier. They have four ELL teachers, four ELL paraprofessionals, and a bilingual liaison to help serve their population.

“If we were to close, there would be a geographically large hole in which our families would be without their central familiar home base for school,” Wampler said. “During parent teacher conferences, we were able to partner with the Lykins Neighborhood Resource Center for a family who needed items for the household. That’s because we were both walking distance for them.”

Examining the demographic map and calculating the median income, Wampler said a potential closure would create a massive gap between the opportunities of education to lower income families.

“To me, it looks like a strategic plan to force a certain demographic out, whether they grew up in KCMO or arrived here seeking a better life,” Wampler said. “Whittier needs to remain consistent for them. What is best for these families? What is best if their child falls ill and they need to pick them up, but they don’t have the transportation to arrive at one of the four different schools we’ve been divided into?”

Wampler said she would never forgive herself if she didn’t speak up.

Christine Shuck, an author, artist and business owner in Kansas City for a decade, moved her family to Northeast from a suburb. She was initially interested in homeschooling because of the district’s lack of accreditation, but after she became the caretaker for her father, her daughter entered 5th grade at Whittier.

“What happened next was an amazing surprise,” Shuck said. “I had a team of teachers dedicated to my daughter’s future, and to this day, five years later, I’m friends with two of her teachers, her homeroom teacher, her science teacher, that provided amazing service for her and educational care and love.”

She has since become a foster mother and adopted mother of two. Her youngest daughter is in first grade at Whittier.

“I realized she has friends in the neighborhood, and I watch them play – I’m half a block away from the school – and I see all these kids getting together, I realize Whittier is the heart of our community, our little neighborhood, and if you take away Whittier, you’re taking away this heart and what is left?” Shuck asked.

She’d hoped to put her daughter all the way through sixth grade at Whittier, and that her 14-month-old son would be able to do the same.

“We have a great team every year, we have great academics, and I don’t care what the school looks like,” Shuck said. “I care about the people that are inside it, and you can’t take that chain, break it up and hope for it to repeat itself somewhere else. It’s great right where it’s at.”

Alissia Canady, former 5th District councilwoman and Deputy Executive Director with the Lykins neighborhood, said she believes this district has to decide who its customers are and how to serve them more effectively.

“All we’ve been hearing about is the buildings and that people here tonight are concerned about the families,” Canady said. “I work in Neighborhood Legal Support as an attorney, and we represent the Lykins neighborhood where Whittier school is located.”

NLS has worked extensively over the last three years on focused community development to rehab houses, to provide affordable housing, to remove blight, and to bring families back into the community. Canady said one of those assets is Whittier.

“There was no discussion in the last three years with that neighborhood about this plan or the possibility of taking away schools,” Canady said. “Millions of dollars have been invested in this community and you’re proposing to take away a strong community asset without any involved discussion.”

She said the immigrant, refugee and ESL families use Whittier not only for education, but as a hub of information and community resource center.

“When we look at the map of who’s been impacted disproportionately, it continues to be Black and brown families,” Canady said. “It’s like this mindset of ask for forgiveness instead of permission. I’ve served as a policymaker, elected official, and we have never gone into established, financially established, politically and civically astute neighborhoods and taken anything away from them without real engagement. Never.”

She said she saw this in 2010 where 30 schools were closed, and watched the district lost accreditation immediately following that. The district regained accreditation earlier this year.

“You guys haven’t even had a chance to put on the effective campaign to promote that to engage more students and you’re already presenting the plan to concede you’re going to lose,” Canady said. “But guess what, you close these schools in Northeast, there are charters that are going to take them… They’re prepared to serve Latino families. KCPS has not done that effectively, including not engaging them around this plan. You have families here today represented by RevED [Revolución Educativa] and others that are saying, ‘We have no idea, no one talked to us.’”

Kelly Allen, a resident of Northeast and employee of the Lykins Neighborhood Association, shared her feelings of hope now that KCPS is fully accredited for the first time since 2011.

“That makes me feel hopeful, and it makes me feel proud,” Allen said. “These kids and educators pulled that off during a traumatic pandemic and that makes me feel hopeful and proud.”

She said she has faith that this is just the beginning of what educators and committed students can do if they continue on this path.

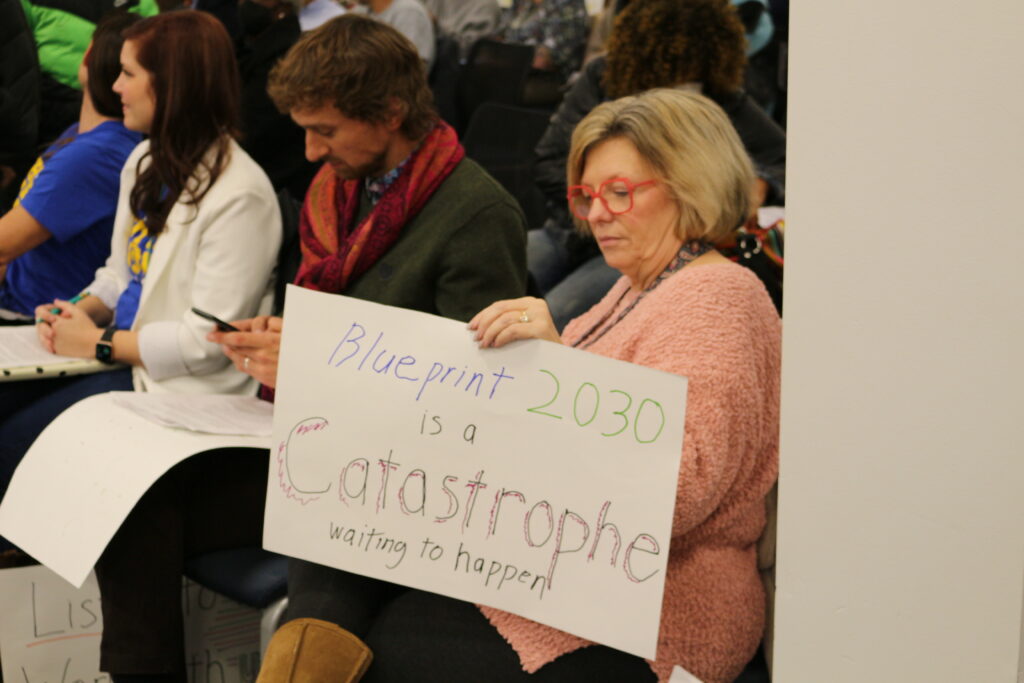

“I want us to let pride and hope steer the ship for these kids while we make big decisions that will impact your city for decades, and I want to see this board treat this district like it is uniquely positioned to educate these kids because it is,” Allen said. “Instead of building on the achievements of these schools, Blueprint 2030 implementation is just going to be the death knell to neighborhood schools in this city. It’ll just be over. Schools that are walkable, rooted in a sense of place, community and legacy will be a thing of the past, and that goes for the schools on the southside and the Northeast.”

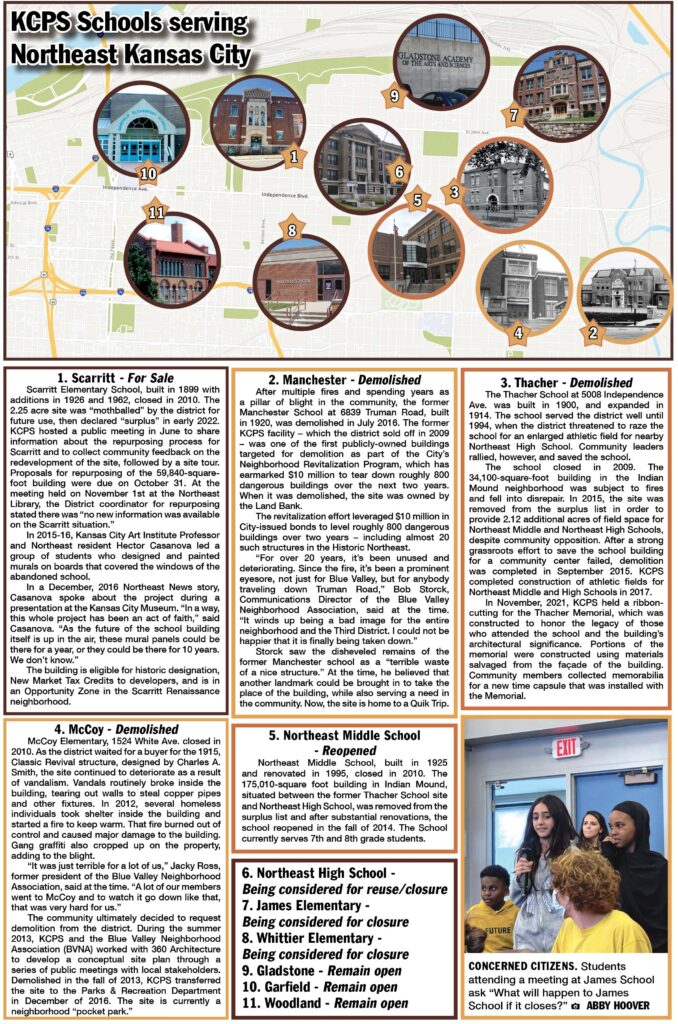

She doesn’t understand why the district is not ambitiously marketing its new accreditation to get kids back in the seats or partnering with the neighborhoods. The plan proposes closing half of Northeast’s remaining schools. Before the district’s right-sizing in 2010, there were 10 schools. Of the schools closed by right-sizing only one remains standing – the vacant Scarritt Elementary at Anderson and Askew. The others burned multiple times before finally being demolished.

“How can we back up this plan when the past and present show us that you guys don’t protect these assets?” Allen asked. “They’re right in the middle of our neighborhoods. I have hope that our kids can continue to advance their achievement. I do not have hope that closing buildings and letting them sit in the middle of our communities and deteriorate or burn is the way to get there.”

She said Northeast neighborhoods will feel a great impact if these schools close. She noted that she’s run the Lykins neighborhood’s agenda for three years, and they didn’t stop meeting during COVID, but the district has never reached out for engagement.

“Nobody heard one word about school closures until a few weeks ago and then we come to these meetings and you justify it saying you’ve been working on it for three years,” Allen said. “You have not been working with us. Partner with us. We are your assets. We really want to dream and scheme ways to get these kids back in the seats because we’re poised to do it right now. Thank you for your time. Please don’t close these schools. It is not a prideful, hopeful move for us.”

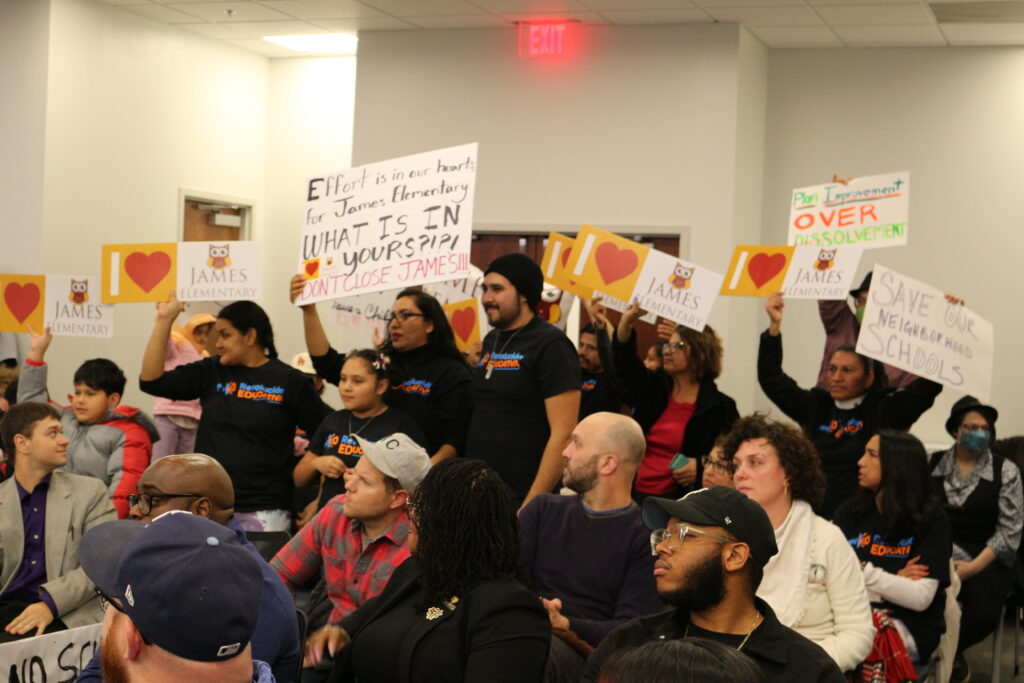

Edgar Palacios, founder of Revolución EDucativa, an education advocacy organization focused on empowering the Latinx community through political engagement and advocacy, lives in the Independence Plaza neighborhood.

“Northeast is a vibrant, diverse community with a strong immigrant population,” Palacios said. “In the Northeast, immigrant families would be hardest hit by the closure of schools – 62% of students at James are limited English proficient, while 50% of students at Whittier are limited English proficient. Forty-seven percent of the combined James and Whittier student population are Hispanic.”

Palacios is most concerned about the voices that are not being heard, voices like Dahlia Rodriguez at James Elementary, who has organized an incredible group of parents committed to keeping James open.

“Language accessibility remains a considerable challenge in the sharing of information and receiving feedback,” Palacios said. “Information being shared is complicated and nuanced, and not easily translated. How do we ensure that those most impacted by the potential closures have access to the best information? As the demographics continue to shift in our community, we must work together to ensure that our community has equity and voice, otherwise our neighbors will remain disenfranchised.”

He asked for additional opportunities for every neighbor in Northeast to share their concerns and hopes for the quality of education their kids deserve, as these are proposed recommendations, not final ones.

Chris Steinauer, STEM teacher at Whittier Elementary and resident of Lykins, is disappointed in the district already, and concerned about the future of his community should the district decide to close his neighborhood school.

“Whittier is on the chopping block, and yet when you ask for community feedback, you reveal yourself as totally unconcerned,” Steinauer said. “Our well funded district decided to cut corners and translate the Blueprint 2030 survey into only one other language – Spanish.”

He asked where the Swahili, Burmese, Pashto, Somali, or Arabic were.

“Where is the equity? Where’s the inclusion? You threatened to close our neighborhood schools and start the process by closing the avenues we can use to speak,” Steinauer said. “This doesn’t happen in Brookside, South Plaza, Hyde Park or Briarcliff, but in the Northeast our unhoused go to abandoned buildings for shelter in the cold. Every winter, buildings here ignite in flames, killing the desperate people inside who just wanted to be warm.”

He asked the board what will happen to the Northeast, James and Whittier buildings.

“What would the district say when it has blood on its hands?” Steinauer said. “Will you all offer thoughts and prayers, and will they only be in English and Spanish?”

Steinauer said the district has shown time and time again that it will offer promises without followthrough.

“Consider, if you will, the 2016 master plan, our classes were supposed to shrink, our walking distances were supposed to shrink,” Steinauer said.

“Instead, our kids walk for longer distances in extreme weather to enter rooms crammed with their peers. Is this equitable? How can I honestly believe the promises of a better experience for our students when it’s documented that you lie? Do not close Whittier. Invest in us, invest in our community. You are responsible for the $6.5 million in repairs we need.”

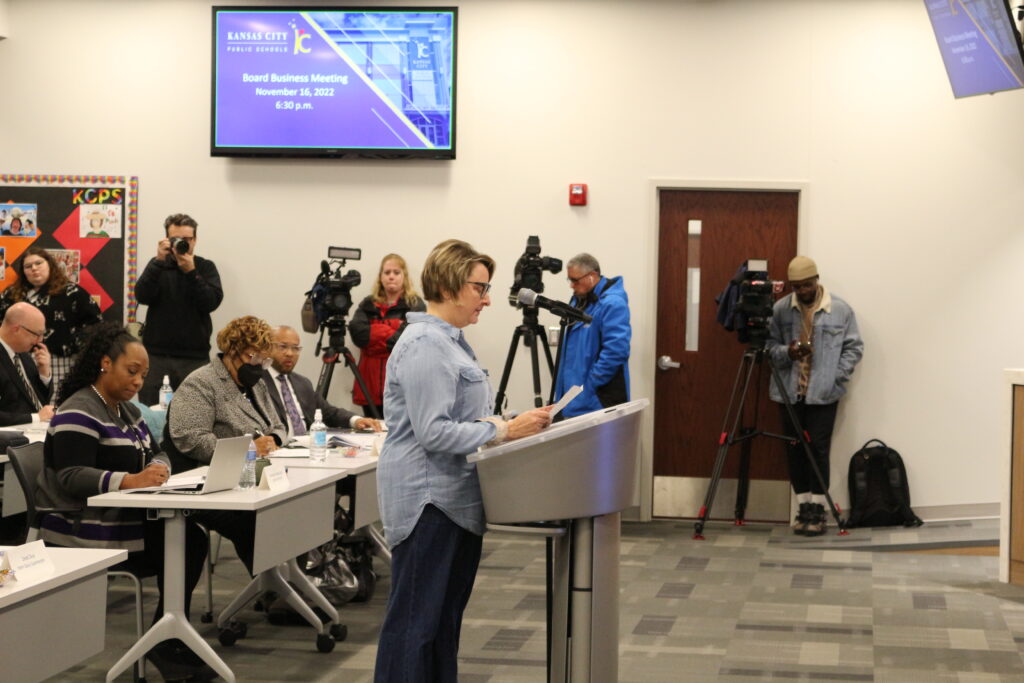

The board plans to vote on the proposed Blueprint 2030 plans at the December 14 meeting at the Board of Education building at 2901 Troost Ave. More info on KCPS Blueprint 2030 and answers to frequently asked questions at public listening sessions can be found at kcpublicschools.org/about/blueprint-2030.

Para Español, https://northeastnews.net/pages/miembros-de-la-comunidad-northeast-rechazan-propuesta-contra-clausura-de-escuelas/.