By Paul Thompson

Northeast News

March 31, 2017

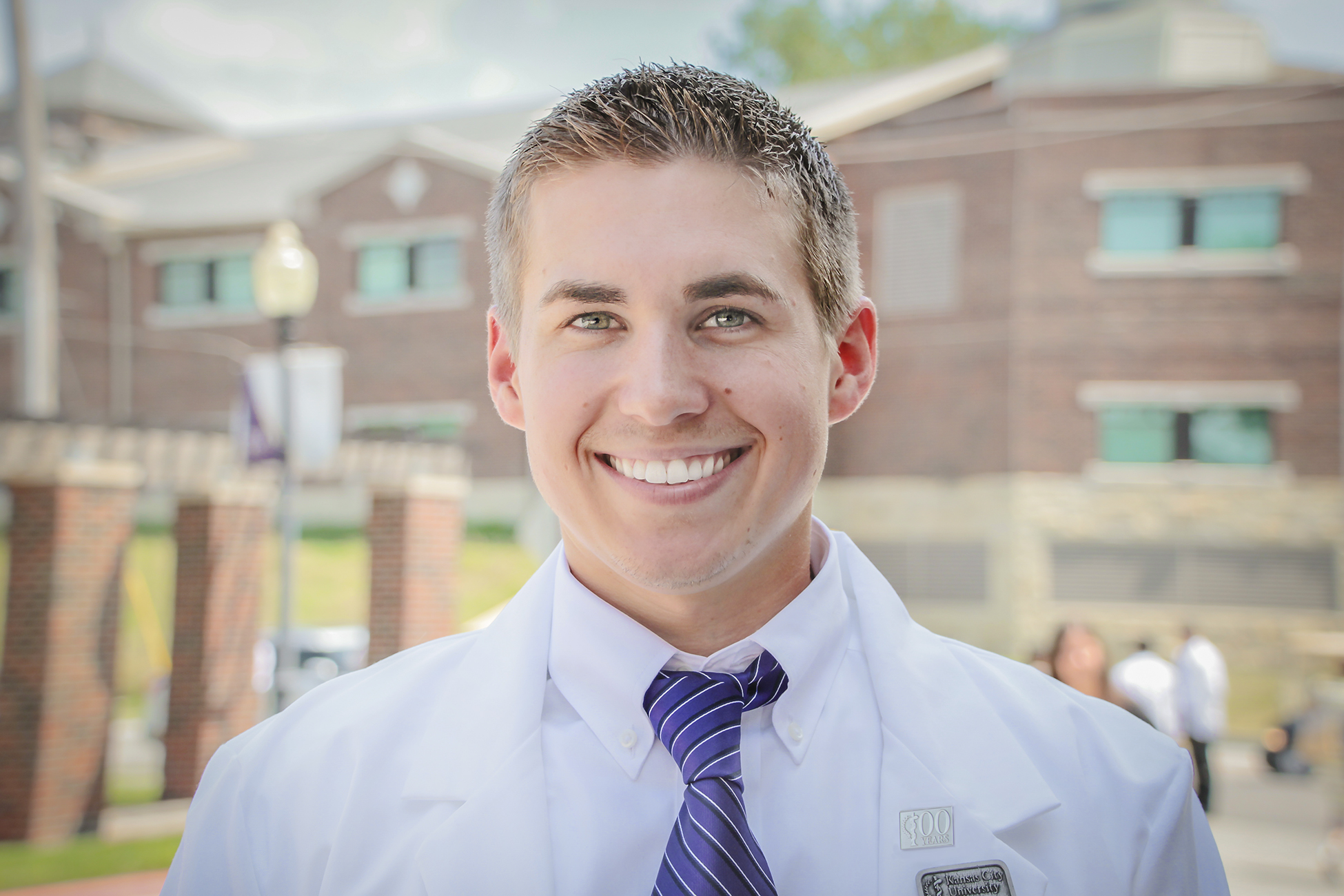

KANSAS CITY, Missouri – That Landon Sowell is completing his first semester of medical school at Kansas City University is something of a miracle.

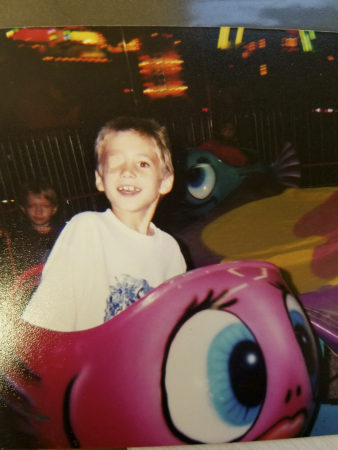

It’s not every day, after all, that a seven-year-old kid suffers a traumatic brain injury, is rushed to a hospital in life-threatening condition, remains unconscious for more than two days, has to subsequently re-learn all of his basic motor functions, and comes out of it all with his vital faculties intact. Any way you slice it, Landon is an anomaly.

The incident that changed Landon’s life occurred on May 20, 2000, and DeAnna Reams was more than an hour away from her son when she got the call that is every parent’s worse nightmare.

Seven-year-old Landon had been kicked in the back of the head by a horse, suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. He was at a small, local hospital in Fulton, Kentucky, near his father’s home in the nearby town of Hickman. Landon needed help.

Seventeen years ago, Dr. Gregory Cox was an internal medicine doctor who occasionally moonlighted on emergency room shifts in Fulton’s 70-bed hospital. He wasn’t a pediatric doctor by trade, but on the fateful day when Landon Sowell entered the ER with that traumatic brain injury, he would have to suffice; at least temporarily. It didn’t take long for Cox to realize that Landon’s injuries were gravely serious, and that the young boy needed to get to an experienced neurosurgeon as soon as possible.

“Even on a cursory exam, it was pretty apparent. The CT scan of his brain that we did only confirmed that,” Cox recently told the Northeast News. “We really didn’t know the full extent of what his injuries were going to be. We knew that he had suffered a traumatic brain injury, and these things can deteriorate further until a patient is stabilized.”

So Cox called Vanderbilt Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, more than a two and a half hour drive away. He requested a helicopter to airlift Landon to Nashville, but there was one problem: a fog had settled in over the area, and the conditions were deemed unsafe for flying. In a race against the clock, an ambulance was going to have to take that seemingly-interminable drive to Vanderbilt.

This was in the year 2000, before the era when every man, woman and child walking down the street carried a smartphone in their pocket. It was DeAnna’s sister who eventually reached her with the scary news that Landon was fighting for his life. DeAnna jumped into her car and raced to Fulton, arriving just in time to catch the ambulance ride to Nashville with her unconscious son.

“I probably drove 120 miles an hour,” DeAnna recalls. “I had blown out a tire and didn’t even know it.”

She reached the hospital before the ambulance departed for Nashville, but the struggles were just beginning.

“They stopped a few times on the way to get Landon’s vitals,” said DeAnna. “They did not think Landon was going to make it.”

From there, Landon remained unconscious for days, laid up in a hospital bed and hooked up to tubes that kept him stabilized. When he awoke, nearly everything Landon had learned in his life had vanished. To this day, Landon says that he can’t really remember anything that happened before the kick.

“I couldn’t move my neck, I couldn’t move my hands, I couldn’t move my legs, nothing,” said Landon. “Every time I had to use the restroom, they had to get me out of the bed. It felt like lifting up concrete bags, just trying to put a puzzle together.”

In those first harrowing days after the kick, DeAnna remembers watching Landon struggle to repeat sequences of words spoken by doctors. His brain was in a sort of stasis, unable even to direct his arms to pick up a ball sitting right in front of him. DeAnna remembers going into an adjacent room and bursting into tears.

In the weeks that followed, DeAnna brought Landon to countless doctors and therapy sessions. On June 9, confined to a wheelchair, Landon was finally allowed to go home. But there was no guarantee that he would ever return to the smart, witty, studious child that he was before the incident.

“When he was seven and all that happened, and they sent him home in a wheelchair and walker, I was just hoping and praying that he was going to be able to take care of himself one day,” said DeAnna. “I was just hoping and praying.”

Doctors had warned that the road back would be arduous, but Landon was eager to accept the challenge. Eventually Landon started regaining his faculties, and what’s more, he was determined to make a full recovery.

“I kind of proved to myself that what they were saying wasn’t necessarily true once I got back to school,” he said. “I saw progress every day.”

Landon was never going to be a professional athlete, and he would forever need to protect his head from heavy blows, but roughly a year later he was more or less back. The recovery gave Landon an appreciation for the medical professionals who saved his life, and eventually, a desire to get into the field himself.

“I wanted to give that same feeling back,” said Landon. “I can relate.”

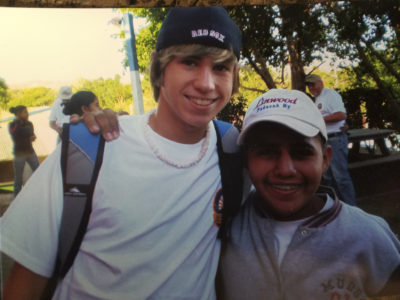

That interest continued as Landon matured, and the curiosity was further stoked during a family mission trip to Nicaragua, as well as a trip to a nearby children’s hospital with his high school’s Beta Club. As a pre-med student at the University of Tennessee-Martin, Landon was expected to shadow a physician to gain experience in the field. He found himself under the tutelage of a familiar face: Dr. Gregory Cox.

“That was humbling for me, to welcome him and have him there to shadow,” said Cox. “He just came with no pay and no college credit. He spent a significant amount of time at our office, watching us go from patient to patient.”

In Landon, Cox saw the attributes that make physicians successful. When describing Landon’s temperament, Cox was reminded of a famous quote from Canadian physician Dr. William Osler: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” In short, Cox found himself believing that Landon possesses the right attributes for the job.

“I think he will be an incredible physician. He’s incredibly passionate, has wonderful social skills, and an incredible way of connecting to people,” said Cox. “What he went through at a very early age instilled in him a lot of that compassion and empathy that he still has to this day.”

While DeAnna isn’t surprised at the success Landon has found in academia, she remains eternally proud of his achievements.

“I’m excited as a mom, but just also impressed as a human being,” she said. “He’s just doing what he said he was going to do.”

For his part, Landon is still figuring out which field he’ll ultimately pursue. He’s in his opening semester at Kansas City University, and there is plenty of time to select his path. Wherever he ends up, though, Landon wants to ensure that he provides the same kind of care he received as a seven-year-old boy toeing the fine line between life and death.

“I would say that emergency medicine is probably #1 on my list,” he said. “There’s going to be some critical care patients, and those are the ones that are really going to make it worth it.”