Michael Bushnell

Northeast News

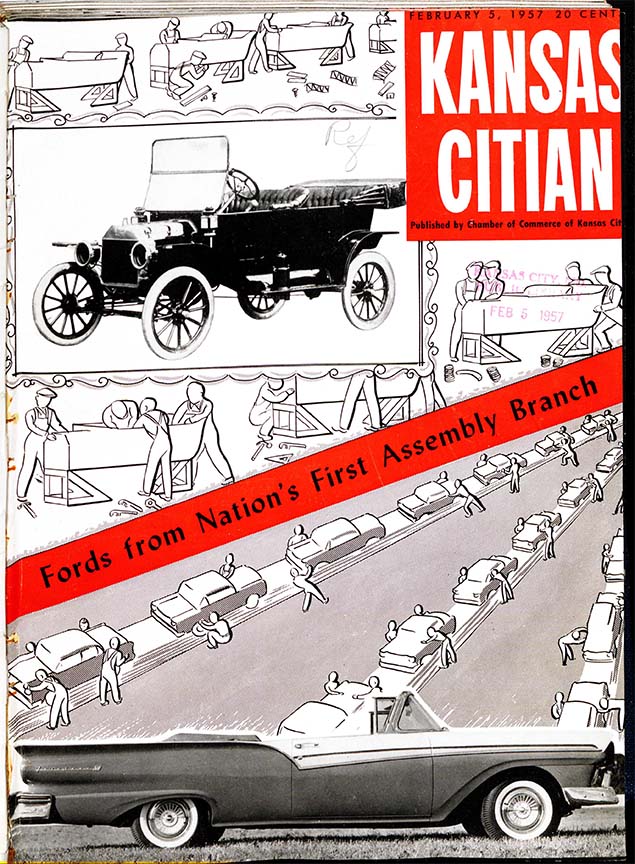

This week’s Historic Postcard focuses on the upcoming Labor Day holiday and a brief history of the Ford Motor Company’s Kansas City Assembly Plant, the first Ford assembly plant outside of Detroit and commissioned by Henry Ford himself.

In early 1906, Ford opened its first branch sales office in Kansas City at 318 E. 11th St. to meet the growing sales needs of Ford in Kansas City. Two models were sold out of the office, mostly as a novelty given the rest of the modern world was still operating with a horse and buggy.

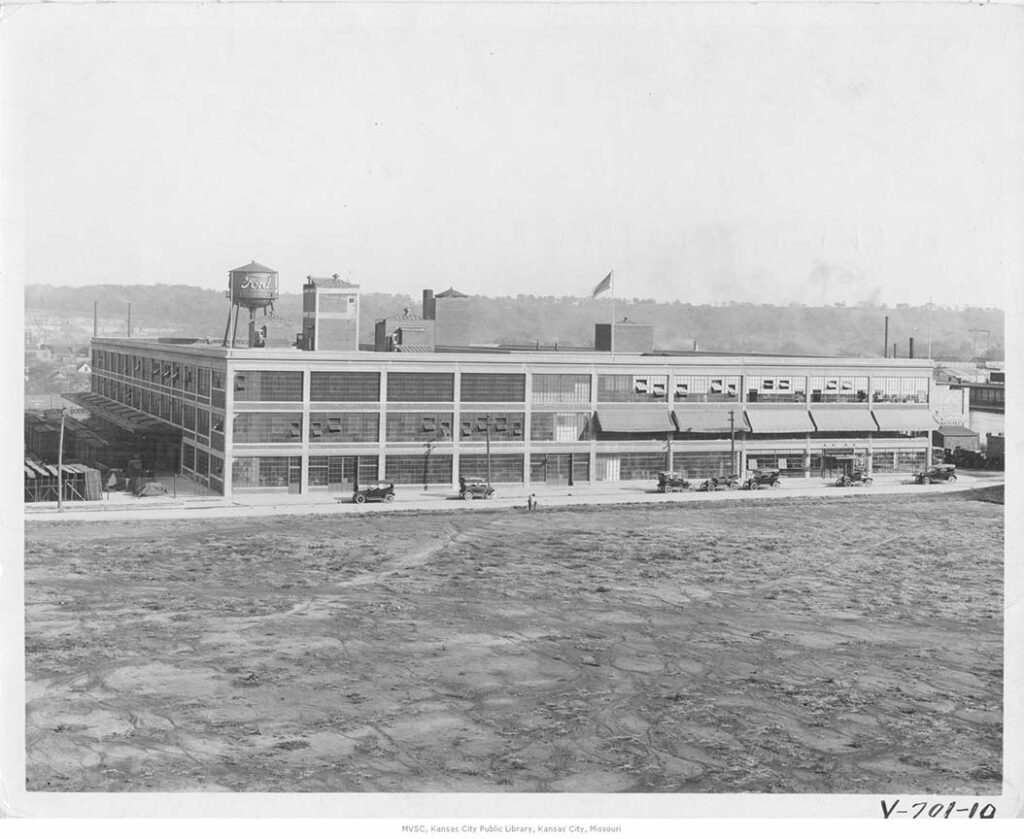

In 1909, Ford announced the building of its first branch assembly plant in Kansas City on a 3.5-acre site in the Blue River Valley at 10th and Winchester. Completed in 1911, the new 32,000-square-foot plant was home to offices, a repair shop and assembly line. The first Model T rolled off the assembly line in the Spring of 1912, producing all of seven Model T Fords a day.

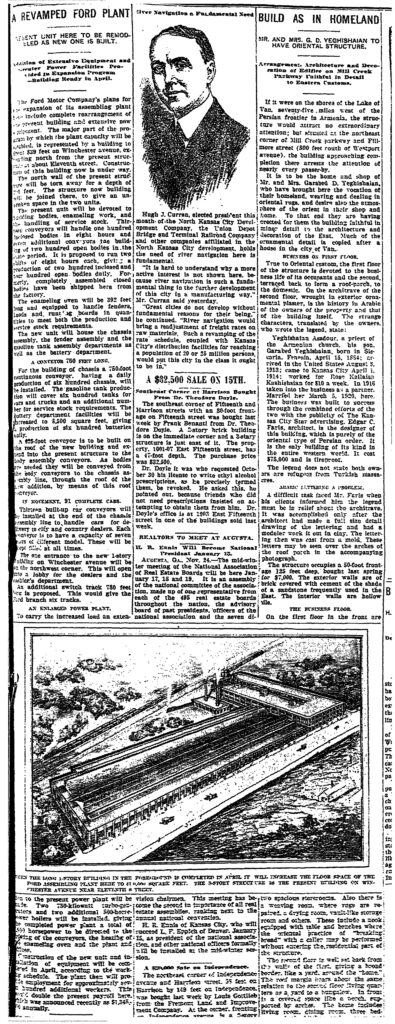

By 1915, thanks to Ford’s advancement of an assembly line system in its Dearborn, Mich., factory, the Kansas City plant was churning out about 100 units per day. Between 1915 and 1924, demand for the new “Tin Lizzy” was so great that the Winchester plant was expanded three times and production jumped from 100 vehicles per day to roughly 500. A Kansas City Star article from November of 1923 documented the planned expansion and spoke highly of a “revamped Ford Plant.”

In 1927, production transitioned from Model T to the new Model A and shortly after that, in 1932, Ford’s new two-door Coupe, Ford’s first equipped with a V-8 engine, began rolling off the line. It would become Ford’s most famed creation and is still one of the most sought after project cars today.

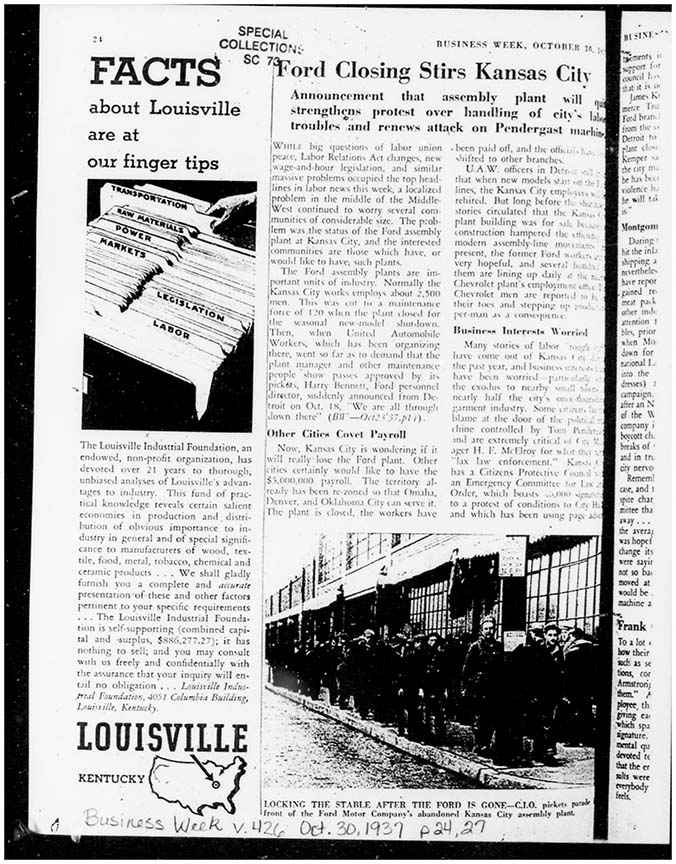

All was not rosy in the auto production world, however. It was the height of the Great Depression and organized Labor Unions, at least prior to the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (known as The Wagner Act), were an unwelcome presence at automobile assembly plants. So unwelcome that they were often ushered off-site by what equated to company goons making sure no organizing activity was being done on company property.

Despite the fact the 1935 Wagner Act was the law of the land, Henry Ford was having none of it, especially after strikes at GM and Chrysler plants in 1936 had galvanized the workers locally at the Winchester plant. United Auto Workers Local 249, chartered earlier in 1937, had been meeting secretly with Ford workers. Henry Ford, upon learning of the attempt to organize, ordered the firing of anyone at the Winchester plant that had a Union card.

At roughly 3:15 p.m. on April 2, 1937, as workers were punching out, foremen began pulling workers aside, telling them to turn in their company badges. Anyone with a Union card lost their job. Local 249 officials learned of the tactic and countered quickly by stopping the production line and ordering an immediate sit-down strike. For the next three years and seven months, Ford locked out UAW members from their plants.

An October 1937 article in Business Week talks about other cities in the region being covetous of the $3 million payroll the Kansas City Ford plant had when it was operating. City Manager H.F. McElroy, a Tom Pendergast lackey, was even called out for not acting sooner to quell the ongoing violence that was a daily ritual at the Winchester plant. James Kemper, president of the Commerce Trust Company that handled the Ford Branch Account at the bank, resigned abruptly from the committee that was to go to Detroit and urge reconsideration of the plant closing, stating, “The committee will be a failure unless the city manager makes a statement that he was mistaken in his policy, that violence has not been stopped, but that he will take the proper steps to see that it is.”

Finally, on May 21, 1941, the National Labor Relations Board ruled in favor of the union, ordering Ford to rehire the discriminatorily fired workers with back pay.

In 1942, civilian production was suspended for the duration of WWII as the plant was re-tooled to make cylinder assemblies for Pratt & Whitney aircraft engines. Following the war, a five acre tract was acquired in Clay County, just south of Liberty. It was under contract to the Department of Defense at the time, manufacturing wings for B-46 Bombers. The transition from military production was undertaken with the goal of being operational by 1956.

On December 28, 1956, the final production vehicle, a 1957 Ford Fairlane Custom 300 rolled off the assembly line at the Winchester plant. Plant Manager Roger Cocks delivered the keys to Roger Stafford of Leonardville, Kan., who operated the oldest Ford dealership in the two-state, Kansas-Missouri District. It was the 2,337,863rd vehicle to be produced at the Winchester plant.

On January 7, 1957, Ford F-100 trucks, a precursor to today’s F-150 trucks, began rolling off the new Claycomo plant’s assembly line. It has been produced at the plant since its inception.

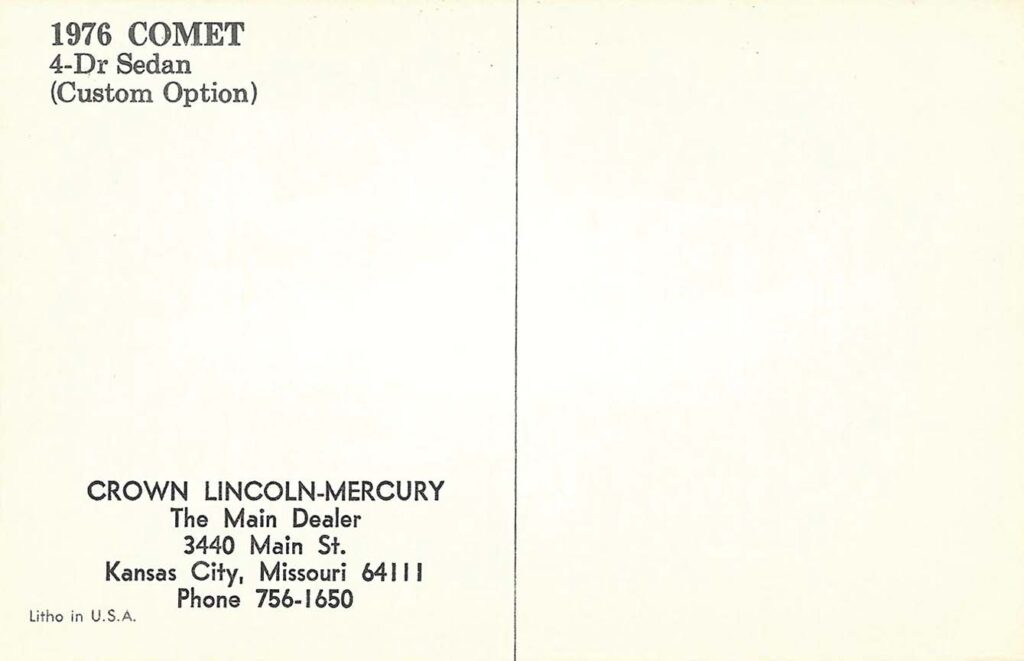

The Mercury Comet, as shown on this week’s Chrome era advertising postcard for Crown Ford-Mercury on Main Street, was likely produced at the Kansas City Assembly Plant. The plant produced Ford Mavericks from 1970 through 1977 and Mercury Comets from 1960 through 1977.

The United Auto Workers Local 249 traces its roots to early in 1937 when it was the first Local to be chartered at Ford. It represents roughly 7,000 members at the Claycomo Plant today.

Today, the old Ford Winchester plant, with its signature sentinel, twin smoke stacks with FORD outlined in dark brick, is home to a number of industrial businesses such as forklift parts and a metal spinning business. The second story darkly paneled office areas are still intact. A small door on the north end leads to a catwalk over the work area that runs the length of the building. It is said when Mr. Ford visited, he would inspect operations from that catwalk.

Additional images and material are courtesy of The Kansas City Public Library, Missouri Valley Special Collections: