By Leslie Collins

Northeast News

July 13, 2011

In meticulous rhythm, Ibrahim Alanbuki jabs his dough like a well-trained masseuse.

With two smacks, he flattens the dough and tosses it around like a pizza crust, plopping it onto what he calls a “bread pillow.”

In the background is the Arabic TV channel broadcasting news and Arabic music. Standing in the kitchen’s sweltering heat, he wipes his forehead with a paper towel.

Alanbuki isn’t making your everyday bread. His speciality is Naan bread, also known as Arabic, Pakistani and Indian bread. Similar to a pita, this flatbread is soft and bigger than a basketball.

It’s not cooked in a conventional oven, either.

Using the round bread pillow, Alanbuki smacks the dough onto the side of a propane powered Tandoor oven and shuts the lid. Fire heats the inside of the cylinder shaped oven and cooks each piece of bread stuck to its side for approximately 30 seconds.

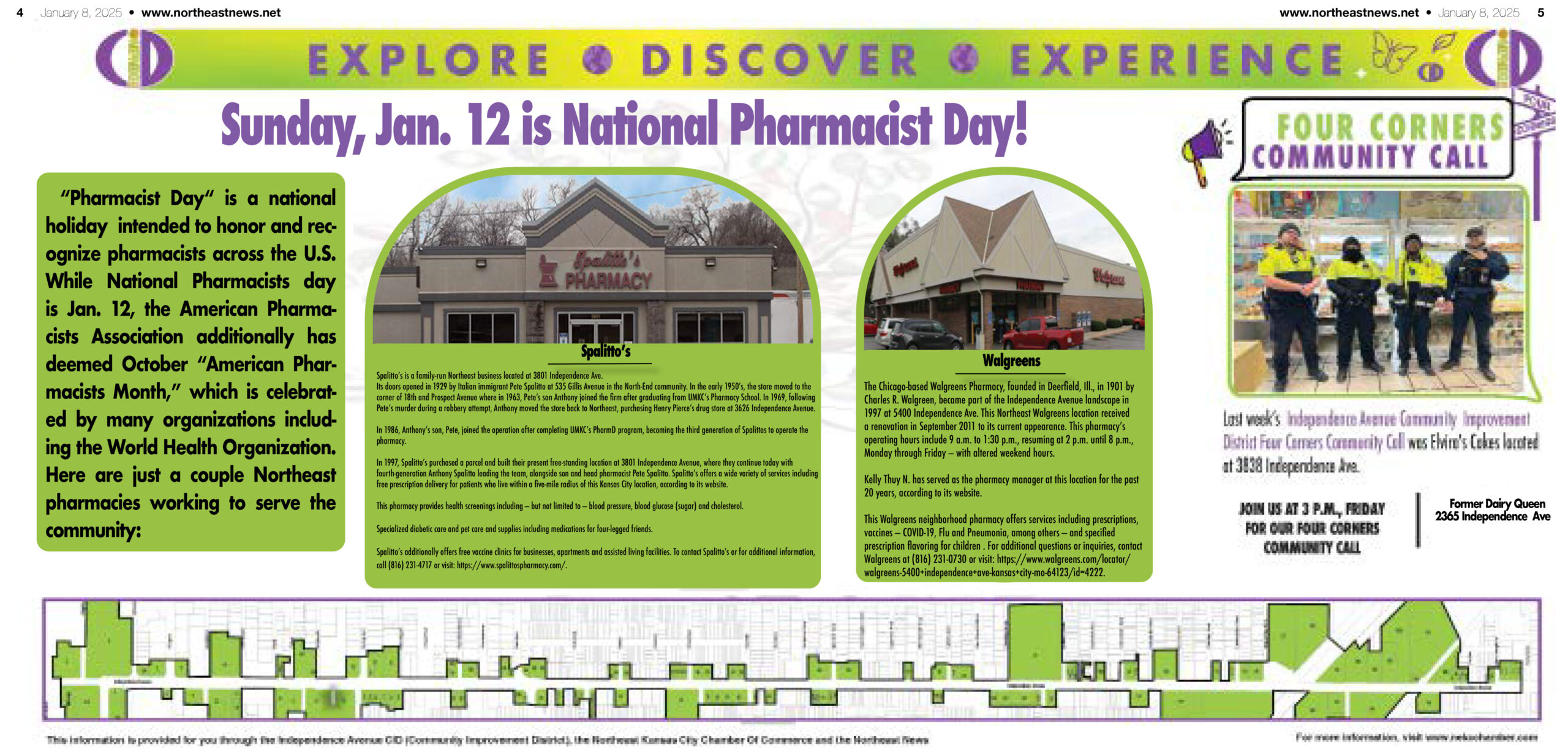

Since 2010, Alanbuki has operated and owned Al-Forat-Bakery, 4436 St. John Ave., in Historic Northeast. Before that, he worked for the U.S. Department of Defense as an Arabic translator.

Alanbuki grew up in southern Iraq and both he and his father were required to serve in the Iraqi military.

“It was nice until the war started between Iraq and Iran,” he said of Iraq.

During the Gulf War in 1991, Iraqi citizens, including Alanbuki, staged a revolution against Saddam Hussein.

“He (Hussein) was killing everybody. He doesn’t care about kids, women, young guys, whatever. He kills everybody,” he said. “We got tired of him. He start war after war and we said, ‘That’s enough.’”

In 1991, Alanbuki became a U.S. prisoner of war for five months and was later released to a refugee camp in Saudi Arabia, where he lived until 1996.

“We were fed well. They (Americans) took care of us. We had a good camp and everything,” he said.

A majority of the refugees relocated to the United States, he said, and Alanbuki became a U.S. citizen and moved to Spokane, Wash., in 1996.

“The language, the religion, there’s a lot of things different (here in the U.S.),” Alanbuki said. “But, the biggest thing is the language. You have to learn to communicate.”

Knowing little English, Alanbuki attended school for two years to immerse himself in the language.

“It was hard on us – all the refugees here. I got used to it. When I learned the language, I (got to) know the people. They were real nice to us.”

His diligence paid off and Alanbuki worked with the U.S. Department of Defense as an Arabic translator from 2006 to 2009. Stationed in Baghdad, he assisted the American military in communicating with Iraqis.

“It was fun, but it’s a really dangerous job,” he said. “Almost everyday we’ve got car bombings, motorists shooting at us, suicide bombers. It’s a dangerous place. It’s a war – a civilian war.”

Despite the risks, Alanbuki wanted to help the American military and his own country fight against terrorists, he said.

Now 43, Alanbuki has chosen a much safer career, baking bread. He learned the technique from the previous owner and expanded the bakery to include a miniature grocery store filled with snacks, spices, Halal meat and other items.

His busiest days are Tuesdays, Fridays and Saturdays where he bakes more than 400 flatbreads for area businesses and individual customers.

He lives with his wife and two sons in Kansas City and doesn’t take his new country for granted.

“I have an amazing life here. I work supporting my family. I have my own apartment, my own car,” he said. “It’s hard for me because I’m away from my family and I get homesick once in a while, but still I was thanking God everyday and I’m still thanking God everyday to live in the United States where there’s freedom.”

Photos by Leslie Collins