Michael Bushnell

Northeast News

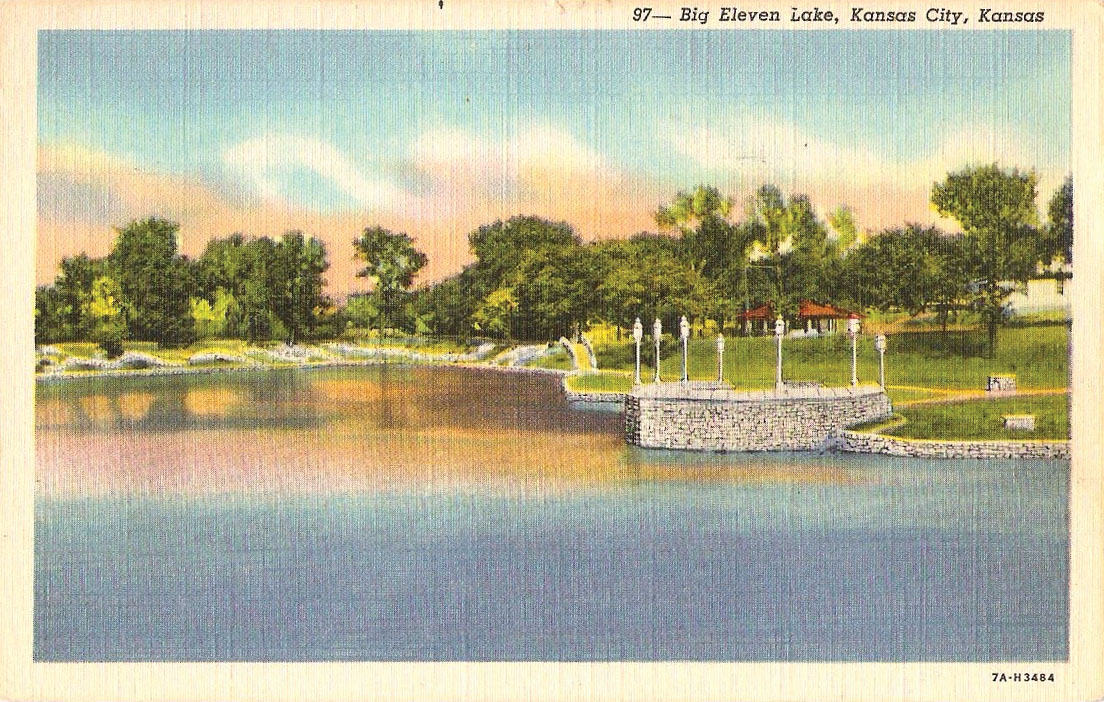

In continuing with our 7-11 themed issue for July 11th, we offer this Max Bernstein-published Linen-type postcard of Big Eleven Lake in Kansas City, Kansas. The lake is all that is left of a larger water themed park designed by noted Kansas City landscape architectural firm of Hare & Hare.

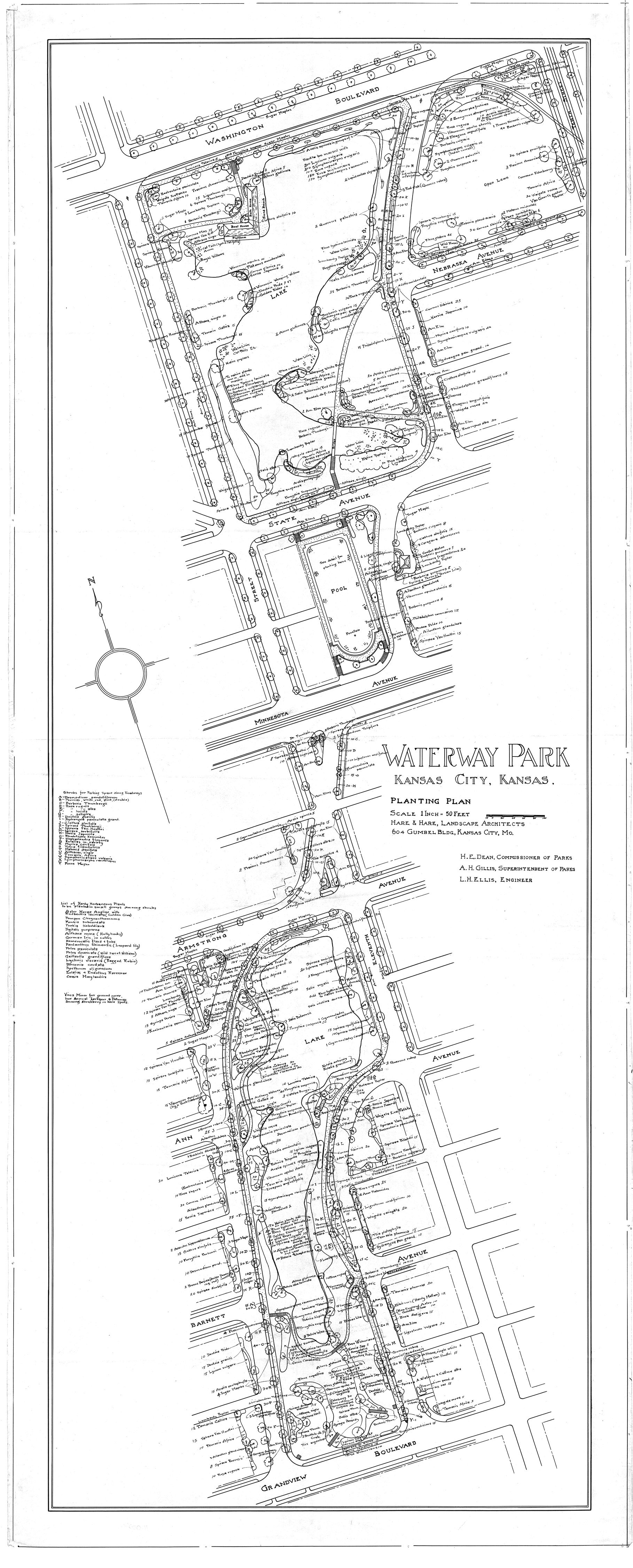

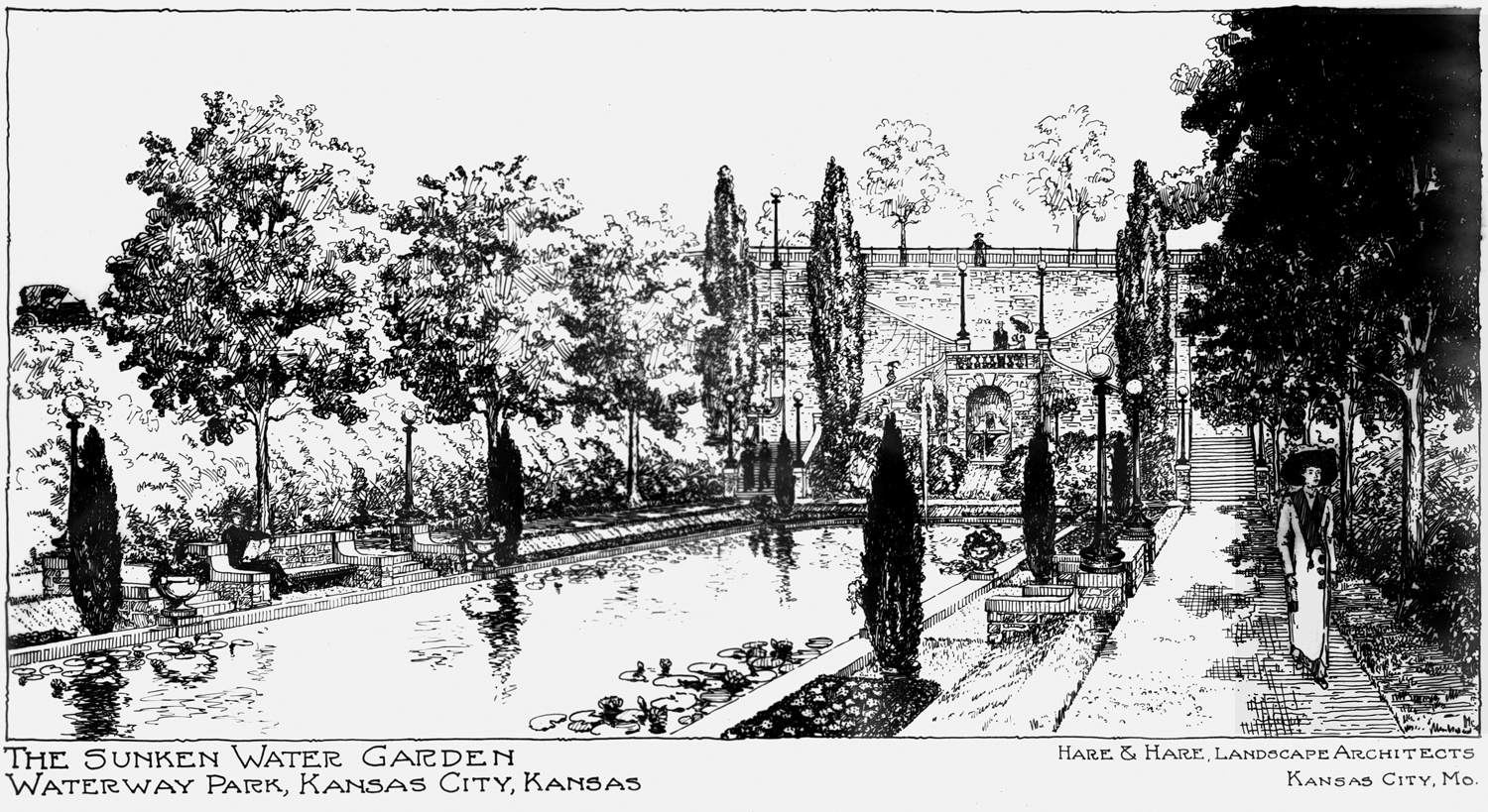

George Kessler, the designer of Kansas City’s Parks and Boulevard system, was tapped by Kansas City, Kansas city officials to replicate Kansas City, Missouri’s boulevard system across the state line. Waterway Park, constructed in a deep ravine, stretched from Washington Boulevard on the north to Grandview Boulevard on the south, incorporated many of the design and landscape features found in Kansas City’s burgeoning Parks system. According to a 1913 article in The Modern Cemetery, the land where the park sits was not suited for development purposes and presented a challenge for the surrounding ground. Called “an unsightly hole,” the landscape design firm of Hare & Hare was called on to design a park with two lakes anchoring each end of the park separated by a large, sunken water garden pool complete with goldfish and water lilies. Built roughly 40 feet below street grade and accessed by two staircases against a limestone wall, the reflecting pool featured natural plantings and a large fountain, much like the palisades built along the west bluff that made up Kersey Coates Drive in Kansas City. The lakes and pool were fed by a series of natural springs that offered a constant supply of water. Big Eleven Lake was the northern lake in that park system.

Sadly, Big Eleven Lake is all that remains of the original Waterway Park system. In 1921 the lake and reflecting pool was filled in and a $6,000 shelter house was constructed on the site of the larger lake at the south end of the park. Baseball diamonds and tennis courts were planned for the sites as well, but newspaper articles of the day note the ball diamonds may not have been built. Today, that end of the park is lined by a fitness walk, and well-worn soccer fields lie at the center of where the shallow lake once was. Newer homes have been built around the park and signs of a neighborhood renaissance are strong. The only clue to the lake’s existence is the earth berm surrounding a depression in the center of the park. No signs of the shelter house’s construction are visible today.

The reflecting pool was filled in, as well, and to this day is used as a parking lot. The only clue to the pool’s existence is an overgrown stone wall near the corner of 11th & Minnesota Ave., with three steps descending to the earth where the pool once existed. Somewhere under tons of dirt and gravel lies what’s left of a once-beautiful urban oasis. In 1983 Congressman Larry Winn secured a $79,000 grant to renovate and improve Big Eleven Lake. During the urban neighborhood boom in the late 1980s and early 1990s, residents reclaimed the park. Like many urban parks, it is used by families living nearby. While the park is still named Waterway Park, Big Eleven Lake, roughly two blocks to the north, is the only remnant of the opulent Kessler/Hare & Hare collaboration in Kansas City, Kansas.

Once again, special thanks to Matt Reeves and the staff at the Central Library’s Missouri Valley Room for his invaluable help and research for this week’s column.

The Modern Cemetery – Volume 23 – Page 71 – Google Books Result

Kansas City Then and Now. Dodd, c2003

Planting plan.

10th Street & Grandview Boulevard, Kansas City, Kansas. 1911-1912.

Presentation rendering of view.