By Kenneth L. Kieser

April 14, 2016

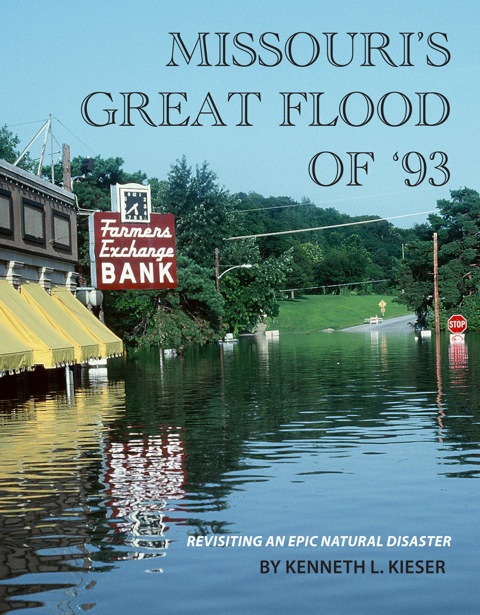

Small ideas occasionally grow into big dreams. I contacted Sara Elder and Sara Wilson of the St. Joseph, Missouri Museum two years ago with an idea for a small display of flood pictures from my book, “Missouri’s Great Flood of “93”—revisiting an Epic Natural Disaster.” Eventually my idea was being developed by a group of photographers, writers and other specialists to create an educational and entertaining exhibit, all led by the brilliant Sara Wilson.

So, on April 15, 2016, this exhibit, “Confluence: The Great Flood of 1993” will open in St. Joseph, Missouri at the Wyeth-Tootle Mansion, 1100 Charles Street, St. Joseph, Mo. 64501. It will be based partly on my book, and I am honored to be the speaker to open this exhibit that will run just over two years. The Army Corp of Engineers and the Missouri Department of Conservation were two organizations out of many that made this exhibit possible. A beautiful moving sand display and many other items, pictures and accounts from this incredible flood will be included.

Floods are not unusual on rivers like the Missouri. A river biologist once told me that floods are a river’s way of cleansing, or cleaning out silt. This silt, enriched with nutrients, eventually creates plants that feed waterfowl in shallow water. But the 1993 flood was more powerful and dangerous. In fact, over 500 counties were affected by this deluge; nine Midwestern states were declared disaster areas. Hundreds of secondary roads and a few major highways and airports were closed. The Midwest had 17,000 square miles flooded. Perhaps even worse, over 30,000 jobs were lost. The flood damage in croplands would eventually drive up world food prices and the total damage caused by the great flood of 93 would total over 20 billion dollars in damages, with at least 10,000 homes destroyed and 50 lives lost. There was no surprise that barge traffic on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers was halted, but few imagined that all railroad traffic in the Midwest would stop, resulting in over $300 million dollars in losses. Over 75 towns or cities were flooded, either in part or completely.

I was blessed to gain an interview with Mike Thompson, chief meteorologist for Kansas City’s Fox-4 News. He had observed wet weather patterns in this region, but had witnessed few contributing events like those that led up to the 1993 deluge. Thompson said that many factors led to the “93” flood. Mount Pinatubo, an equatorial volcano in the Philippines, erupted the year before and spewed enough ash into the stratosphere to cool the entire globe for about four years. The jet stream actually helped create 1993’s heavy rains. The jet stream is high-speed winds at the top of our atmosphere. Without the jet stream air collapses, killing thunderstorm activities. Because of Pinatubo, the air in June was cool and rainy while the jet stream was sitting on top of us. This condition carried into July, extremely late in the year to find the jet stream this far south. A

combination of Mount Pinatubo cooling the entire globe and the jet stream displaced over Midwestern states instead of farther into the northern plains where it should have been by that time of year was the beginning. Hurricane El Nino feeding a lot of tropical moisture up into the Southwest United States was another contributing factor. This added moisture caught up in the jet stream, creating stormy cycles throughout the Midwest. The soil had become saturated in earlier months and heavy rains in July had nowhere to go. This created incredible runoff that eventually made it to the rivers.

Some areas actually received more than four feet of rain in this condensed period. Flood records were broken at 49 individual points on the Missouri River and 44 on the Mississippi. Many stretches on the river broke flood records by over four feet.

The Kansas River basin was soaked with torrential rains during the June-July period of 1993. Much of this rain fell in the Kaw River basin. The downpour with water coming from Kansas tributaries and the Missouri River was the beginning of this major flood.

Other factors causing the flood were melting snows in the winter of 1992-1993 followed by rain in states north and west of Kansas City and St. Louis. By late 1993, groundwater levels were saturated in the Central Great Plains. A wet fall with spring snowmelt provided few places for rain to soak in, and the vast rainwater runoff began. Most people just considered it to be an unusual year, never realizing the build-up of water that would soon push downstream to create one of the greatest floods of our lifetime as rain kept falling in biblical proportions. All homemade levees failed and seven federal levees were lost to massive amounts of flood water. This historic deluge may have been worse for towns downriver if the river levees held. Several million gallons of flood waters spilled into river-bottom acreage, wiping out precious row crops. Many simply called it an act of God, but a plethora of factors contributed to the phenomenon that many people still call the 500-year flood.

“Confluence: The Great Flood of 1993” will open on April 15, 2016, at the Wyeth-Tootle Mansion and run through 2018. The exhibit will include a social history of the flood of 1993, discuss other major floods in Missouri’s history, and will explore the meteorological causes of the 1993 flood. The Great Flood of 1993 will be explored through videos and photographs, objects such as sand bags and Anheuser-Busch cans of drinking water, and narratives of people who experienced the flood. Contact the Museum at 816-232-8471 or email sjm@stjosephmuseum.org for more information. The Museum hopes to continue building an archive of the Great Flood of 1993 as we approach the 25th anniversary of the event. I’’ll see you there!